A New Stage in the Rivalry Between the Great Powers? - International Reports

International Reports

During the Cold War, the Atlantic and Pacific in particular were considered key theatres of geopolitical conflict between the two super‑powers, the USA and the Soviet Union. But in the 21ˢᵗ century, the (re-)emergence of Asia, particularly of China and India, has lent the Indian Ocean greater economic and security-related significance. Some observers believe the Indian Ocean is the world’s most important ocean, the “center stage for the 21ˢᵗ century”. “Whoever controls the Indian Ocean dominates Asia. (…) In the twenty-first century, the destiny of the world will be decided on its waters” – at first glance, this quote, attributed to the former US Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, seems to overestimate the importance of the Indian Ocean. However, these words highlight its growing geo-economic and geopolitical significance and have shaped the strategic thinking of decision-makers in China and India.

The Indian Ocean has particular geopolitical importance due to its role as a transit zone for the world’s trade routes and because its narrow points of access are easy to control. These maritime chokepoints are not only important for trade, they are also critical points for global energy security. The two most important “maritime oil chokepoints” are located in the Indian Ocean: the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca. In 2015, 17 million barrels of oil passed through Hormuz and 15.5 million barrels through Malacca every day, representing 30 per cent and 26 per cent of all seaborne-traded oil. The increasing economic importance of the Indian Ocean has led to more players becoming active in the region. For example, the abrupt surge in piracy off the Somali coast since 2005 has highlighted the vulnerability of international shipping and prompted many nations to engage militarily in the region. Germany has been supporting the Atalanta counter-piracy operation for the protection of free seafaring off the coast of Somalia since 2008. China in particular has increased its economic activity in the region and in the last few years has also ramped up military operations, also to protect its investments and interests. India perceives this as a growing threat to its interests, which has led to an expansion of its own economic and military activities and an increased cooperation with other countries. Other countries, such as the US, Japan, Australia and France, also plan to or have already stepped up their involvement in the face of future rivalries between the great powers.

The Indian Ocean is extremely important to Germany because of the country’s export-oriented economy. Germany depends on unfettered sea trade and the unhindered access to raw material and export markets in Asia. The growing rivalry in the Indian Ocean between the increasingly active great powers is a threat to maritime security and therefore to Germany’s economic and security interests in maintaining maritime supply routes. During his state visit to India in March 2018, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier stated in an interview that Germany “as a globally active trading power (…) has a keen interest in peace and stability (…), and increasingly in an open, safe Indian Ocean”. Germany’s strategic priority should therefore be to expand security policy cooperation with its partners in the region and, as stated in the White Paper on Security Policy of 2016, to continuously review and refine regulatory “agreements and institutions” in the Indian Ocean and actively work to maintain them. As the geostrategic importance of the Indian Ocean continues to grow and, along with the Pacific, the ocean is increasingly becoming the stage for conflicts between great powers, it is therefore vital that effective institutions are implemented for preventing conflicts.

Growing Economic Importance of the Indian Ocean

The economic importance of the Indian Ocean will continue to grow in the coming years, though it is already considered “the world’s preeminent energy and trade interstate seaway”. At present, some 50 per cent of global container traffic and 70 per cent of the world’s oil trade pass through the seaways of the Indian Ocean. Roughly 30 per cent of all trade is handled in Indian Ocean ports. The high economic growth experienced by countries that border the Indian Ocean – exemplified by India’s forecast 7.4 per cent growth in 2018 – indicate that the importance of trade will continue to increase in the coming years and decades. India is particularly dependent on trade across the Ocean because of its geographic location. Access is blocked by Pakistan to the west and the Himalayas to the north, forcing it to import 80 per cent of its oil across the Indian Ocean, and to ship 95 per cent of its trade via this route. However, trade between the countries of the region only accounts for 20 per cent of trading activity in the Indian Ocean. For countries outside this region, partic‑ularly Europe and the East Asian and Pacific states, the Indian Ocean is of enormous importance for their trade relations. Trade agreements such as that between the EU and Japan and South Korea and the planned agreement between the EU and India will swell this main artery of world trade still further.

The Indian Ocean is also tremendously important for energy security. Every day, nearly 30 per cent of global oil seaborne trade and 30 per cent of global LPG seaborne trade passes through the Strait of Hormuz, which connects the Indian Ocean with the Persian Gulf. 80 per cent of this goes to Asian markets, mainly China, Japan, India, South Korea and Singapore. The Strait of Malacca, located between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, connects the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. For China, this is probably the most important chokepoint, as some 80 per cent of Chinese oil imports transit the Malacca Strait. Along with China, this conduit is also of great importance to many other countries, as half of all the world’s ships would have to find an alternative route if the Strait of Malacca were to close. The fact that the significance of the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca is likely to increase rather than decline is also due to China and India’s growing need for energy. By 2030, China will likely overtake the US as the world’s largest consumer of oil. And after 2025, India’s oil consumption is set to grow faster than that of China.

Along with its monumental significance as a transit zone for goods and energy carriers, the Indian Ocean also has vast stocks of fish and minerals. Between 1950 and 2010, fish catches increased more than thirteen-fold to 11.5 million tonnes and aquaculture in the region has grown twelve-fold since 1980. Most of the fish stocks in the coastal regions have been overfished, but there are still large stocks of deep-sea fish. The sea bed also holds significant mineral deposits. Along with manganese nodules containing nickel, cobalt and iron, the Indian Ocean also holds sulphide deposits containing copper, iron, zinc, silver and gold. Various rare earths are also present in the Indian Ocean, though it is not yet commercially viable to extract them. Along with other nations, China and India are actively exploring and exploiting these resources and Germany has also been exploring sulphide deposits in the southwestern Indian Ocean since 2015.

Increasing Geo-Economic Rivalry Through Connectivity Initiatives

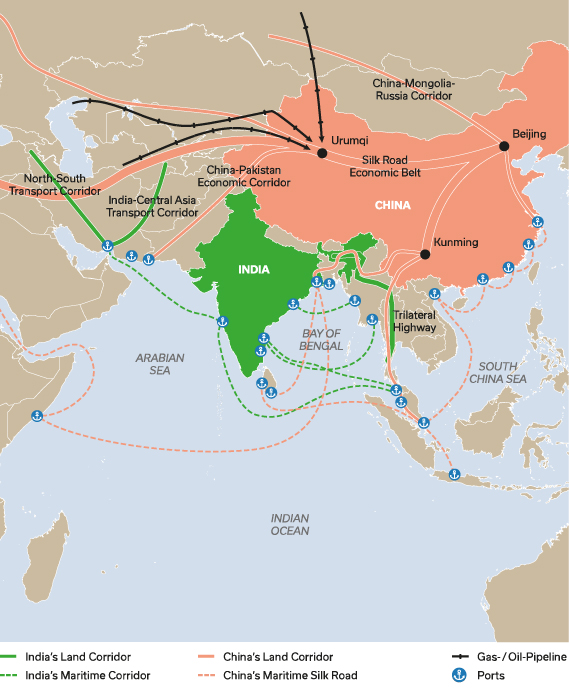

The establishment of initiatives for improved connectivity in the Indian Ocean region is changing its overall economic and political picture. The aim of these initiatives is to exploit economic potential, eliminate the current lack of infrastructure investment, achieve greater economic integration and gain influence. The main players, between which geo-economic rivalry has consequently increased, are China and India.

China’s Maritime Silk Road

Perhaps the most significant connectivity initiative was launched by China in 2013. The “Maritime Silk Road” is a development strategy to boost infrastructure connectivity throughout Southeast Asia, Oceania, the Indian Ocean and East Africa and enhance China’s interests. It is the maritime complement to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which, with its other land-based elements, focuses on infrastructure development in Central Asia towards Europe. China’s economic and strategic interests overlap in this initiative. It also has the aim of increasing China’s influence in Asia. From an economic perspective, China is hoping to increase its exports, expand existing and open new markets, export Chinese technical standards, and reduce transport costs through improved connectivity and the possibility of eliminating overcapacity. Politically and strategically, the aim is to connect the previously economically weak western regions of China, shorten supply routes and reduce dependence on transport through chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca. It is also an attempt by China to build closer ties between states and to take on a leading role in the region. To this end, China is focusing on significant investment, expanding port facilities, constructing oil and gas pipelines and developing infrastructure projects along its maritime supply routes. Critics of the project have questioned the economic viability of these projects and to what extent they merely serve China’s geopolitical intentions. There are concerns that China’s supposedly commercial investments could also be used for military purposes. There are also concerns that these large-scale investments are also structured in ways that could allow China to exert undue leverage over the domestic and foreign policies of heavily indebted recipient countries.

Fig. 1: Connectivity Intitiatives of China and India

The weight of the overlap between China’s economic and strategic intentions is clear in a number of infrastructure investments. The expansion of the port of Gwadar in Pakistan is part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which will connect the Chinese province of Xinjiang with the Indian Ocean in order to improve the province’s accessibility and promote its economy. At the same time, however, the port is geographically close to the main supply line for China’s oil imports from the Persian Gulf. Despite official statements that this is strictly for economic purposes, it can and will also be used militarily by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Chinese investment in other ports, again supposedly for strictly economic reasons, has been followed by visits and deployments of warships and submarines, as has been seen in Colombo and Djibouti.

High interest rates on Chinese loans have caused several countries to become heavily indebted as a result of the Silk Road projects in China. Sri Lanka is a prime example of how China can use this debt to gain more rights and thus more control. At China’s urging, the government converted the debt into a controlling equity stake in the port of Hambantota and leased it to China for 99 years, ultimately giving China complete control over the previously financed infrastructure project. Similar cases have occurred with investments in the expansion of the port facilities at Gwadar in Pakistan, Payra in Bangladesh, Kyaukphyu in Myanmar and in the Maldives. As mentioned above, this ultimately confirms concerns that China could exert pressure on indebted countries as a result of its loans. This has also led to tender processes for contracts in these port facilities being restricted to Chinese companies, which for all intents and purposes precludes free and fair competition.

India’s Fragmented Response

India is seeking to counteract China’s growing influence in the region and in the Indian Ocean and boost its own dwindling influence by launching its own connectivity projects. However, compared to the Belt and Road Initiative and its “Maritime Silk Road” component, such initiatives are much smaller, more fragmented and more reactive in character. These activities are mainly former initiatives that are being resumed or expanded, a result of India’s lack of financial resources, human resources and administrative skills. In 2015 India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi put forward his vision for India’s activities in the Indian Ocean with his concept of Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR). India’s objective with this vision is to create a climate of trust and transparency, to ensure all countries comply with international maritime rules and norms, to strive for peaceful conflict resolution and to enhance maritime collaboration.

In practical terms, India initially concentrated on its immediate neighbourhood in order to link this region more closely – a region that the World Bank calls the world’s least integrated region. Since 2015 the South Asian Associ‑ation for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has been paralysed by the conflict between Pakistan and India and was largely neglected by India in favour of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). This organisation of countries that border the Bay of Bengal was established in 1997 and was given a new lease of life by India in 2016. Its main aim is to build closer ties between India, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Thailand, both economically and politically. A recent meeting of national security advisors discussed the need for investment in infrastructure, security issues and maritime security in particular. In 2014 Modi upgraded the Look East policy, which had been in place since the early 1990s, to an Act East policy in order to strengthen cooperation with countries such as Japan and the ASEAN member states. India is also pushing ahead with the expansion of its own port facilities. As part of the Sagar Mala Project, India is seeking to build six mega-ports and create special economic zones centred around them. It will also grant the ports greater autonomy in order to facilitate trade.

Perhaps the most ambitious project at the moment is the investment in the port of Chabahar in Iran. India is keen to bypass Pakistan and establish links to the countries of Central Asia – the India-Central Asia Transport Corridor – and to Russia – the North-South Transport Corridor. So far, however, only one grain delivery has been made to Afghanistan and no other successes have been reported. The worst setback for India is probably the fact that Iran recently permitted China and Pakistan to use the port facilities, too.

A new and previously unthinkable feature of India’s foreign policy is the idea of working with its neighbours on projects in South Asia. Working with USAID in Afghanistan or the USA in the construction of overhead lines in Nepal would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. Other projects include the expansion of the port of Trincomalee in Sri Lanka, planned jointly with Japan, and the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), also planned with Japan, which aims to link the African countries bordering the Indian Ocean more closely with the Asian region. However, all these projects are still at the draft phase.

Growing Geopolitical Rivalries

China’s increased security commitment in the Indian Ocean is motivated by a desire to protect its maritime routes to the Persian Gulf, and therefore its oil supply. It also wants to secure its investment in the port facilities along the coast, which are intended to reduce its geostrategic dependency on the Strait of Malacca. Over the last few years, China has not only modernised its armed forces and expanded its naval capacities, but it also stated in its 2015 Defence White Paper that its operations will not only focus on protecting its coastline but also place more emphasis on the high seas. China has been active in the Indian Ocean since 2009, initially combating piracy in the Gulf of Aden. Since then, it has significantly expanded its military presence and in 2016 it built its first military base outside its own territory, in Djibouti, though the Chinese claim this is merely a logistics centre and supply base. This is a distinct departure from China’s previous policy of not deploying troops outside its own borders and clearly shows that China is prepared to engage militarily in order to defend its interests in the Indian Ocean. China has also expanded its military activities, docked warships and submarines in ports close to maritime supply lines, and sent out patrol ships under the guise of combating piracy. This has fuelled concerns in India and the US that China’s investment in port expansion has been undertaken with a view to using them for military as well as economic purposes. China’s actions in taking control of the port of Hambantota as described above also demonstrates that China is striving for greater freedom in the use of its maritime infrastructure in foreign countries. Its increasingly aggressive presence in the South China Sea, most recently through the deployment of missiles on the Spratly Islands, has also given rise to concerns that a conflict in the South China Sea could spill over to the Indian Ocean and that China could take a more offensive stance in the Indian Ocean, similar to its actions in the South China Sea.

In response to China’s growing military presence, perceived as a “string of pearls” strategy, along with its encirclement by Chinese bases, and its own regional and global ambitions, India has ramped up its maritime capabilities in recent years. With its Maritime Security Strategy of 2015, India formally expanded its sphere of action in the Indian Ocean. In line with this, India has expanded its maritime capabilities with its own nuclear-powered submarines and the aircraft carrier Vikramaditya, which entered service in 2013. The country is currently expanding its fleet and another aircraft carrier is currently under construction, this time in India itself. India has also strengthened its bilateral security cooperations. India has signed agreements to expand its military cooperation with the island states of Seychelles, Mauritius, Maldives and Comoros, and it has also installed radar stations for monitoring maritime activities in a number of countries, including Mada‑gascar.Senior officials from the USA, Japan, Australia and India also met in November 2017 to revive the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), which had been interrupted due to differences of opinion on foreign policy. However, all the participating countries now seem to have generally accepted that this strategic framework is necessary due to China’s growing military activities in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Military cooperation with the USA has also been expanded since the early 2000s. Its highlight is the annual Malabar naval exercise, in which Japan also takes part. Yet, despite its conflicts with China, India still refuses to enter a formal alliance to counter China.

Following China and India, the USA is the most important strategic player in the Indian Ocean region. It has a number of major naval bases, and large naval units are stationed in the Persian Gulf, Djibouti and Diego Garcia. In view of the economic problems and China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour, the USA is endeavouring to find strategic partners in the region. The USA is looking for allies to help counter what it perceives as China’s attempts to challenge the existing world order. On the European side, France is particularly active in the Indian Ocean because of its overseas territories and has recently expanded its cooperation with India. In March 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron agreed with Modi that both countries would in future be able to use the naval bases for their fleets. Without referring directly to China, Macron made it clear that: “The Indian Ocean, like the Pacific Ocean, cannot become a place of hegemony”.

As Macron’s words suggest, the ramping up of activity, particularly on the part of China, has been accompanied by an increasingly unified view of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Back in 2007, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe spoke to the Indian Parliament of a “confluence of the two seas”. Abe advocated that Japan and India, as like-minded democracies, should promote freedom and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region. His vision was a region that includes not only the Asian states but also the United States and Australia; a region in which people, goods, capital and knowledge can move freely and unhindered. The strategy aimed to combine the economic dynamics of Asia and Africa and envisaged greater regional integration along the Indian and Pacific coasts through infrastructure development and improved connectivity. At the same time, this strategy represented a geopolitical counterweight to China’s activities, which have the aim of establishing the country as a maritime power. The concept of the Indo-Pacific has become more significant over recent years. In the USA’s latest National Security Strategy, the concept of the Indo-Pacific is found for the first time in an official US security document. The region is presented in a very stylised way as the scene of a struggle: “A geopolitical competition between free and repressive visions of world order is taking place in the Indo-Pacific region”. This wording was also reflected in the speeches of US President Donald Trump on his first trip to Asia, during which he repeatedly stressed the importance of a “free and open Indo-Pacific”. The idea behind this phrase is that in future the democratic Pacific rim countries in the Indian Ocean and the countries bordering the Indian Ocean in the Pacific should be more committed to security and the freedom of the high seas. This was also confirmed by former US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson when he spoke of viewing the region as a “single strategic arena”. This new description serves to curb China’s activities in both the Indian and Pacific Oceans and to unite the states that are concerned about this development.

The growing geopolitical rivalries recently emerged during the government crisis in the Maldives in February 2018, where China has become an important political player in recent years through major investments in local infrastructure and tourism. In early February, the Constitutional Court of the Maldives ordered the release of political prisoners and overturned the sentences against the former president and other opposition politicians living in exile. President Abdulla Yameen responded by imposing a state of emergency. As a result, opposition politicians called for Indian intervention to restore political democracy in the Maldives. India, however, showed restraint and an Indian government official explained: “We must keep an eye on regional stability, while the consequences of intervention are never foreseeable” What he meant by this was clarified in an article in China’s Global Times. The article called for restraint from India and threatened that China would take any necessary steps should India intervene.

Lack of Security Mechanisms Leads to Growing Insecurity

The increasing rivalries in the Indian Ocean are fuelling insecurity and the risk of confrontation seems to be growing due to a lack of security mechanisms. The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) is one organisation that counts most of the bordering countries as members. However, its activities and institutions are largely dependent on which country is currently leading it. Cooperation under the auspices of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), which brings together the highest military forces of the navies of the bordering states and other important states in the Indian Ocean, has also so far failed to yield any effective consultation mechanisms. The institutions and coordination mechanisms set up within the framework of anti-piracy missions are also threatening to disappear as the latter draw to an end, despite the fact that the common interest in securing trade routes was particularly evident here. The importance of the Indian Ocean as a major transit zone for world trade, the pressing need for all countries to protect their own sea routes, and the progress of globalisation – none of these have so far led these states to decide that such protection could be afforded more effectively by joint security efforts rather than by going it alone. China’s activities in particular have created an environment of unpredictability and mistrust in the Indian Ocean. China’s strategy of using debt traps to blackmail other states, of using supposedly civilian port facilities for military purposes, and of deploying submarines in the Indian Ocean under the pretext of combating piracy (although they are clearly unsuited to this task) indicates that China is not interested in joint efforts but is mainly seeking to strengthen its own position, even if it is at the expense of others’ security. If China continues down this path, this will lead to a growing sense of threat – a feeling that already prevails in some countries, such as India – and as a result China’s opaque motives for action will in individual cases increasingly be perceived as hostile and directed against its own interests. This will lead to a counter-coalition of the states that feel threatened, and indeed the first steps towards this have already been taken through the reformation of QUAD. The USA’s stylised description of the rivalry as a competition between repressive and free world orders also points to a further escalation of conflict. It remains to be seen whether China will continue to fuel insecurity through its policies and ultimately provoke reactions from other states, or whether it will return to the rules of the liberal world order that made China’s rise possible, but it seems rather unlikely in view of its current activities in the Indian Ocean. It is therefore in the European and especially German interest to get more involved in stability of the Indian Ocean region. In addition to its strong economic interest, Germany also has an overwhelming interest in upholding its values by maintaining the freedom of the high seas and, above all, the liberal world order.Despite its geographical distance, with its commitment to Operation Atalanta, Germany has already demonstrated that it is ready to take action in the Indian Ocean to defend these interests.

– translated from German –

-----

Peter Rimmele is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s office in India.

Philipp Huchel is a Research Associate at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s office in India.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.