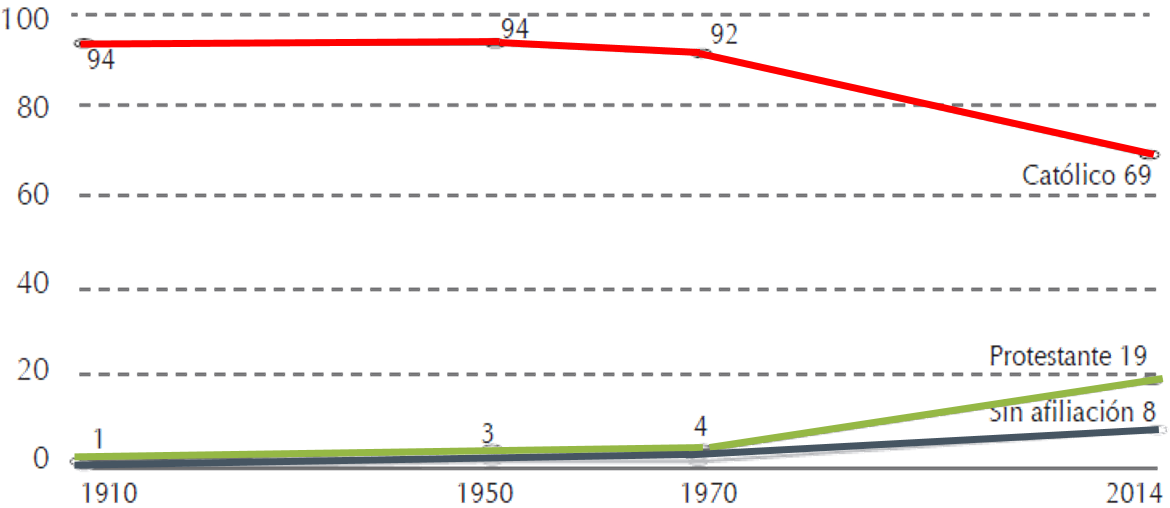

The transformation of the Latin-American religious landscape has been dramatic. Over the last 20 years, neo-evangelical churches shifted from being a minority phenomenon to become a sizable portion of the population. As their share of the electorate grew higher, so did their political ambitions. Having been traditionally unpolitical, evangelicals no longer shy away to influence political processes and have the ability to change election outcomes. 2018 was certainly a defining moment in Latin America, when Jair Messias Bolsonaro surprisingly won the presidential elections in Brazil with the help of the country’s main Neo-Pentecostal leaders, which used to support left wing presidents such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva or Dilma Rousseff. In Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-wing candidate, won the presidential elections with the support of a small evangelical party (PES), which strongly advocated against a so-called “gender ideology”. Finally, in Costa Rica, Fabricio Alvarado, an evangelical Member of Parliament, won the first round of the country’s presidential election due to his opposition to same-sex marriage. He was later defeated in the second round after making denigrating comments about a local patron saint (“Virgen de los Ángeles”). Yet, these three elections show how divers evangelical movements are. None of the aforementioned candidates were able to attract the support of all evangelical groups. In Brazil, for example, only about 60 percent of the evangelicals supported Mr. Bolsonaro. In none of the cases was the “evangelical vote” enough to lead a candidate to victory. That being said, while Evangelicals do not yet determine elections of their own they can tip the electoral balance in favor of one candidate.

Professor Guadalupe distinguishes two types of evangelicals in politics, which differ in their ultimate motivations: 'evangelical politicians' and ‘political evangelicals.' Evangelical politicians are evangelicals who participate in established political parties and behave in a similar way as for example Catholic politicians. They are citizens, inspired by Christian values seeking the common good. Therefore, their success would depend on their professional performance as politicians regardless of their evangelical confession, although their evangelical background might benefit them one way or the other. On the other hand ‘political evangelicals’ are upstart religious leaders in politics without experience in public management, who seek to use their 'religious capital' to make gains in their 'political capital'. Political evangelicals end up being religious 'interest group operators' rather than politicians seeking the 'common good' acting as believers and not as citizens. For this reason, they will depend exclusively on their religious parishoners; but many times, they are not even able to manage to win the vote of their own fellow believers. The majority of evangelicals who participate in politics today belong to the group of political evangelicals, who see their electorate primarily as believers rather than citizens.

Historically in the 1970s and 1980s, the mission of the evangelicals in Latin America was much defined through the notions of anti-communism and anti-Catholicism. This gradually changed after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Yet, there still exist sentiments against “Castrochavism” (neologisms referring to Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez). Today, Catholics and Evangelicals often join forces in Latin-America, even though not for ecumenical but for political reasons to jointly advocate against a perceived “gender ideology” and for pro-life and pro-family moral agendas.

Traditionally, the political participation of Evangelicals manifested itself in three models. First in the form of an evangelical confessional political party or movement, made up of and led exclusively by “Evangelical brothers”, who under a “religious mandate” want influence in local governments to facilitate the evangelization of society. Second, the “evangelical political front” that is led by Evangelical brothers of different denominations but open to other actors who share their political ideals. Finally, the “evangelical faction”, which consists of the participation of Evangelical leaders in electoral processes within already created political parties or movements, based on electoral alliances. Historically, the evangelical faction model has been more effective than the 'evangelical party' or the 'evangelical front'.

Evangelical’s participation in politics varies by region. Central American experiences a high percentage of evangelical population in the region with four countries already exceeding 40% (Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala). The Central Americans are closest to creating electoral unity. Interestingly enough, in this part of the world also Catholics—despite the decreases in the numbers of people affiliated to this church—have a strong religious commitment very similar to the Pentecostal one and Catholics and Evangelicals join more easily around a common political agenda such as the “pro-life” and “pro-family.” The average percentage of the evangelical population in South America ranges between 15% and 20% and the likelihood that an issue around religious values (such as a 'moral agenda') would be a determining factor in a presidential election is lower than in Central America. In most South American countries, evangelical movements have formed a well-established political 'lobby' in defense of “Christian values” and against what they call “gender ideology.” However, evangelicals have not succeeded to make these topics a central theme of election campaigns, mainly due to the existence of a well-established and institutionalized secular party system.

A very particular case constitutes Brazil, where Pentecostal churches are engaged in electoral campaigns through official candidates and political parties. Strategically, the corporate model of official candidatures has shown to be the most successful one as it avoids the dispersion of the vote. During elections, one can observe 'denominational votes' rather than a 'confessional votes.' Although more than 30% of the population is evangelical, electoral preferences are segmented by belonging to different denominations and political parties. With regard to future developments, the extreme growth of evangelical churches might lead to a situation that they will constitute a majority in the Brazilian society in 20 years. To understand the success of Jair Bolsonaro in the last presidential election in particular within the evangelical electorate, co-author Fabio Lacerda explained that Bolsonaro had positioned himself as a candidate strongly opposing the Brazilian workers’ party Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) and the Lulism movement, which had resonated well with evangelical voters. With regard to the situation in Colombia, evangelical political movements are no national phenomenon but support is concentrated on large and medium-sized cities and is extremely low in rural areas. This explains why out of the three evangelical parties, only two were successful in elections; however; since the government of Colombia does not have a parliamentary majority, it needs to rely on evangelical parliamentarians to create ad-hoc majorities on specific topics. The political power of evangelicals could also be seen during the Colombian peace plebiscite in 2016, which was derailed in particular due to a campaign against the final agreement orchestrated by evangelical movements. The outcome caught the government off-guards and much surprised international observers, since polls indicated a different result. Co-author Velasco Montoya explained that three factors motivated evangelicals to get involved in the referendum. The first is related to xenophobia and the constant influx of refugees and migrants from Venezuela following the internal conflict caused by President Maduro, Evangelicals promulgated successfully the believe that the peace process was ideologically promoting Castrochavism. Second, evangelicals disapproved the strong gender perspective of the peace accord, which included stipulations centered on gender equality and women’s rights. Third, evangelicals—who were especially victims of guerrillas forces—never came to terms with the aspect of reconciliation and showed a lack of understanding why criminals would get rewarded with political power for their atrocities.

In conclusion, Professor Guadalupe and his co-authors rejected some popular assertions. First, there does not seem to be a confessional vote: Evangelicals do not necessarily vote for an evangelical candidate, just because they are evangelical. Secondly, evangelicals have not yet transformed their presence in society into political power. Compared to their presence in societies there is a political under-representation of Evangelicals in politics throughout Latin America, with the percentage of evangelical political representatives being much lower than the percentage of the evangelical population. Thirdly, evangelicals have not achieved ecclesial or political unity. What constitutes a blessing for their growth is at the same time a curse for their ecclesial unity. Thematically, the “pro-life” and “pro-family” moral agenda (opposition against abortion, same sex marriage and the so-called “gender ideology”) is the only domain that could, at present, agglutinate the evangelical vote.

Share of Catholics, Protestants and people with no religious affiliation in Latin America

Historically in the 1970s and 1980s, the mission of the evangelicals in Latin America was much defined through the notions of anti-communism and anti-Catholicism. This gradually changed after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Yet, there still exist sentiments against “Castrochavism” (neologisms referring to Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez). Today, Catholics and Evangelicals often join forces in Latin-America, even though not for ecumenical but for political reasons to jointly advocate against a perceived “gender ideology” and for pro-life and pro-family moral agendas.

Traditionally, the political participation of Evangelicals manifested itself in three models. First in the form of an evangelical confessional political party or movement, made up of and led exclusively by “Evangelical brothers”, who under a “religious mandate” want influence in local governments to facilitate the evangelization of society. Second, the “evangelical political front” that is led by Evangelical brothers of different denominations but open to other actors who share their political ideals. Finally, the “evangelical faction”, which consists of the participation of Evangelical leaders in electoral processes within already created political parties or movements, based on electoral alliances. Historically, the evangelical faction model has been more effective than the 'evangelical party' or the 'evangelical front'.

Evangelical’s participation in politics varies by region. Central American experiences a high percentage of evangelical population in the region with four countries already exceeding 40% (Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala). The Central Americans are closest to creating electoral unity. Interestingly enough, in this part of the world also Catholics—despite the decreases in the numbers of people affiliated to this church—have a strong religious commitment very similar to the Pentecostal one and Catholics and Evangelicals join more easily around a common political agenda such as the “pro-life” and “pro-family.” The average percentage of the evangelical population in South America ranges between 15% and 20% and the likelihood that an issue around religious values (such as a 'moral agenda') would be a determining factor in a presidential election is lower than in Central America. In most South American countries, evangelical movements have formed a well-established political 'lobby' in defense of “Christian values” and against what they call “gender ideology.” However, evangelicals have not succeeded to make these topics a central theme of election campaigns, mainly due to the existence of a well-established and institutionalized secular party system.

A very particular case constitutes Brazil, where Pentecostal churches are engaged in electoral campaigns through official candidates and political parties. Strategically, the corporate model of official candidatures has shown to be the most successful one as it avoids the dispersion of the vote. During elections, one can observe 'denominational votes' rather than a 'confessional votes.' Although more than 30% of the population is evangelical, electoral preferences are segmented by belonging to different denominations and political parties. With regard to future developments, the extreme growth of evangelical churches might lead to a situation that they will constitute a majority in the Brazilian society in 20 years. To understand the success of Jair Bolsonaro in the last presidential election in particular within the evangelical electorate, co-author Fabio Lacerda explained that Bolsonaro had positioned himself as a candidate strongly opposing the Brazilian workers’ party Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) and the Lulism movement, which had resonated well with evangelical voters. With regard to the situation in Colombia, evangelical political movements are no national phenomenon but support is concentrated on large and medium-sized cities and is extremely low in rural areas. This explains why out of the three evangelical parties, only two were successful in elections; however; since the government of Colombia does not have a parliamentary majority, it needs to rely on evangelical parliamentarians to create ad-hoc majorities on specific topics. The political power of evangelicals could also be seen during the Colombian peace plebiscite in 2016, which was derailed in particular due to a campaign against the final agreement orchestrated by evangelical movements. The outcome caught the government off-guards and much surprised international observers, since polls indicated a different result. Co-author Velasco Montoya explained that three factors motivated evangelicals to get involved in the referendum. The first is related to xenophobia and the constant influx of refugees and migrants from Venezuela following the internal conflict caused by President Maduro, Evangelicals promulgated successfully the believe that the peace process was ideologically promoting Castrochavism. Second, evangelicals disapproved the strong gender perspective of the peace accord, which included stipulations centered on gender equality and women’s rights. Third, evangelicals—who were especially victims of guerrillas forces—never came to terms with the aspect of reconciliation and showed a lack of understanding why criminals would get rewarded with political power for their atrocities.

In conclusion, Professor Guadalupe and his co-authors rejected some popular assertions. First, there does not seem to be a confessional vote: Evangelicals do not necessarily vote for an evangelical candidate, just because they are evangelical. Secondly, evangelicals have not yet transformed their presence in society into political power. Compared to their presence in societies there is a political under-representation of Evangelicals in politics throughout Latin America, with the percentage of evangelical political representatives being much lower than the percentage of the evangelical population. Thirdly, evangelicals have not achieved ecclesial or political unity. What constitutes a blessing for their growth is at the same time a curse for their ecclesial unity. Thematically, the “pro-life” and “pro-family” moral agenda (opposition against abortion, same sex marriage and the so-called “gender ideology”) is the only domain that could, at present, agglutinate the evangelical vote.