EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In November, the situation in the air war against Ukraine changed little, despite a slight positive trend towards more intercepted drones and missiles. The Russian military continues attacking critical energy infrastructure and residential areas. Since 2022, Ukraine has lost 70% of its electricity-generation capacity. Civilians also continue to be deliberately targeted.

- Russia still cannot fully meet its production goals for long-range drones. However, the situation remains very serious due to highly concentrated and constantly changing attack waves.

- In November, Russia deployed 5,444 long-range drones (+3% compared to the previous month), 108 cruise missiles (–33%), and 106 ballistic missiles (–2%) against civilian targets. Drone numbers changed little over the past three months; missile use remains very high compared to previous years.

- The interception rate for drones rose to 84% (October: 80%, September: 87%). In November, 884 drones could not be intercepted (previous month: 1,077). The interception rate for ballistic missiles rose to about 30% (previous month: 15%), while the cruise missile interception rate remained between 70 and 85%.

- A total of 996 drones and missiles were not intercepted in November (previous month: 1,213). The total payload of unintercepted explosive payload, which is a key indicator of destructive potential, decreased, but remains the second-highest value of the year.

- The Ukrainian armed forces continue to rely on deliveries of new electronic warfare, air defence systems, as well as ammunition. In particular, integrated air defence (IADS) needs to be further improved.

- Russian Shahed drones have been modified to attack Ukrainian airborne air-defense units using air-to-air missiles.

- In November, Ukraine's new drone defence systems became operational. Serial production of the Octopus interceptor drone began after long delays. France delivered a multi-layer FPV-drone protection system. The Sting interceptor drone was successfully used against Geran-3 drones.

- Ukraine remains dependent on Western deliveries of precision long-range missiles (Deep Precision Strike, or DPS capabilities), as its own systems lack the necessary capabilities in terms of navigation and payload. If Ukraine can exert sufficient pressure on Russia with these long-range weapons, Ukraine will have a better negotiating position to end the war.

SITUATION IN NOVEMBER. ANALYSIS AND TRENDS

In November, the situation in the air war in Ukraine changed little, despite a slight positive trend towards improved interception rates. The Russian army attacked Ukrainian cities and civilian targets with 5,444 drones in November (3% more than in the previous month; peak in July: almost 6,300). This corresponds to around 180 drones per night.

Russia has not yet been able to meet its production targets for long-range drones (↗ Monitor Vol. VIII), yet continues to successfully strike civilian infrastructure. The proportion of decoy drones (mostly of the Gerbera type) has fallen slightly to 38%. 62% of all long-range drones deployed by Russia were of the Shahed 136/Geran-2 type.

Interception Rates of russian Missile und Drone Attacks

The daily intervals and intensity of the waves of attacks have hardly changed since the summer. More than 400 drone attacks were counted on seven nights in November. On the night of 29 November, there were 596 drone strikes. Except for a brief period in August around the Alaska meeting between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin (↗ Monitor Vol. VIII), there is no clear correlation between political events and the intensity of the attacks.

INTERCEPTION RATE SLIGHTLY IMPROVED

The number of unintercepted drones and missiles decreased in November relative to the previous month, despite an increase in Russian drone launches, because Ukrainian air defence performed more effectively. In November, 884 drones could not be intercepted (October: 1,077). The interception rate for drones thus rose slightly to 84% (October: 80%, September: 87%).

Cruise missiles were counted significantly less than in the previous month: 108 (-33% compared to October). Ballistic missiles were deployed 106 times (-2%); which is still a very high figure compared to previous years (in 2024 and 2025, the annual average was approximately 60 missiles per month). The interception rate for ballistic missiles (Iskander-M and Kinzhal) improved to around 30% in November (previous month: 15%). The interception rate for cruise missiles remained unchanged, ranging between 70% and 85% depending on the type. A total of 996 airborne weapons, including drones, were not intercepted in November (previous month: 1,213).

The actual destructive potential of the attacks is evident in the total amount of unintercepted explosive payload, meaning the combined payload of all drones and missiles. In November, this figure stood at 69,540 kg, 25% less than in October (93,700 kg). Ballistic missiles accounted for 31,880 kg (–23%), cruise missiles for 10,420 kg (–49%), and Geran-2 drones for 27,240 kg (–15%). Despite the increase in drone attacks and the virtually unchanged number of ballistic missiles, the explosive payload delivered to the target – and thus the destructive potential – has decreased significantly because the interception rates of Ukrainian air defence have improved. However, it remains the second-highest value in the course of the year (highest value in October: 93,730 kg).

Total Payload of Unintercepted Drones and Missiles, in Kg of Explosives

Russia will continue trying to overwhelm Ukrainian air defense with combined high-intensity waves of drones and missiles. Shahed drones are also used for reconnaissance flights to prepare attacks with sophisticated weapon systems that have significantly greater destructive power. Ukraine must continue expanding its Integrated Air Defence System (IADS) to counter missiles and drones “at each altitude, speed and trajectory of target” (↗ RUSI, 27.11.2025). IADS refers to the coordination and integration of all air- and ground-based air defence systems, including those responsible for reconnaissance and communication. The integration of very different systems, managing tactical decision-making processes, and ensuring continuous radar coverage in complex terrain, particularly around cities, pose a special challenge (↗ Tom Cooper, 30.11.2025).

ATTACKS ON INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE CIVILIAN POPULATION

Russia is continuing its air war against the civilian population’s basic means of survival in Ukraine unabated. As in previous weeks, energy and heat supplies remain at risk (↗ Monitor Vol. X). Targeted large-scale strikes in the south-east of the country led to prolonged power cuts and disruptions in train services (↗ Suspilne, 8.11.2025). Since 2022, Ukraine has lost about 70% of its electricity generation capacity. Replacement equipment for repairs is in short supply. Ukrainian energy companies are facing a 30% shortfall in their budgets. The EU will provide six billion euros to better protect and repair damaged energy facilities (↗ Kyiv Independent, 18.11.2025).

The Russian army is also continuing its targeted attacks on civilians, such as the attack on a bus in the Dniprovskyj district (Kherson region) on 3 November, a minibus in Zaporizhzhya on 5 November, and an ambulance in Kherson on 22 November. In Kharkiv, Russian attacks have destroyed or damaged 12,500 homes since 2022, leaving 160,000 people homeless (↗ Suspilne, 20.11.2025). The city of Ternopil was hit particularly hard on 19 November: in a single night, 31 people were killed and 94 injured, with 13 people still missing (↗ Suspilne, 21.11.2025).

Frontline regions in particular remain under great pressure from attacks using drones, missiles, and glide bombs. Compared to previous months, it is notable that the attacks are concentrated more heavily on specific regions. Once again, the regions of Kharkiv, Dnipro, Odesa, Donetsk, and Chernihiv were hardest hit in November.

Days with Damage Reports by region, November 2025

SPOTLIGHT:

I. Technical developments in Ukrainian air defence

Electronic warfare against ballistic missiles

The use of the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal hypersonic weapon and the Iskander-M missile has nearly doubled in recent months. At the same time, the interception rates for these missiles declined significantly in the summer.

The Ukrainian army faced several challenges: modified software that allows for a steeper trajectory and possibly faster evasive maneuvers, the use of decoys, and a higher concentration of missiles within a single wave of attack. Data for the individual attack nights show very large variations in the interception rates of ballistic missiles. They range from zero to 100% (↗ RUSI, 18.11.2025).

In recent weeks, however, interception rates have improved overall. According to an evaluation of all daily reports from the Ukrainian Air Force, at least 135 ballistic missiles have already been intercepted this year.

According to the Ukrainian special unit ‘Night Watch’, Kinzhal missiles have been repeatedly intercepted using electronic warfare (EW) (↗ 404media, 20.11.2025). This involves disrupting the navigation system of the Kinzhal missiles, which depend on communication with the Russian GLONASS satellite system (jamming).

The Ukrainian EW system ‘Lima’ feeds the attacking missiles with false coordinates (spoofing). It is capable of overloading the missiles' navigation system to such an extent that sensors in the missile are switched off, causing the missile to crash – up to 200 km away from its intended target (↗ Forbes, 19.11.2025).

The Ukrainian armed forces continue to require deliveries of EW systems, ammunition, general air defence systems, and specialized Patriot systems to repel Russian air strikes (↗ recommendations in Monitor Vol. X). That this is possible is demonstrated by the analysis of the last major attack night on 29 November, when the Russian military conducted a total of 632 attacks. All four Iskander-M missiles deployed were intercepted (↗ KPSZSU, 29.11.2025).

Russian threat from modified missiles

The Russian armed forces are continuously adapting their Shahed drones in order to break through Ukrainian drone defences. Along the front lines, modified Shahed drones have been observed attacking Ukrainian aircraft and helicopters used for drone defense. For the first time, an R-60 air-to-air missile was found in a downed Shahed drone (↗ Serhij Beskrestnow, 1.12.2025).

Geran-2 drones have modified communication and navigation systems enabling real-time control, partly via radio signals received from occupied areas of Ukraine.

In November, an Iranian-made Shahed-107 medium-range drone was observed on the front line (↗ ISW, 29.11.2025). This model has a long range and real-time reconnaissance capabilities, enabling it to operate with greater precision (↗ Defence-network.com, 11.7.2025). Since August 2025, Russian forces have repeatedly attacked Ukraine with ground-based 9M729 (Novator) cruise missiles, which can be equipped with nuclear warheads – a clear violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) (↗ Reuters, 31.10.2025).

Deployment of new anti-drone systems

In mid-November, after a long delay, serial production of the Ukrainian Octopus interceptor drone began (↗ Denys Schmyhal, 14.11.2025). It can be deployed primarily at night and at various altitudes, and it is resistant to electronic warfare (EW). Launch conditions are also simpler than for other drone systems.

Octopus originates from a British-Ukrainian initiative and can also be used against Russian drones that fly at particularly high or very low altitudes. The interceptor drone was developed in 2024 and was already scheduled for series production in February 2025. However, bureaucratic and legal hurdles prevented production from starting – with devastating consequences.

With Octopus, Ukraine now has a scalable model for better drone defence. However, the RUSI think tank warns against overly high expectations and against overestimating the new interceptor drone as a universal solution for defending NATO's eastern flank (↗ RUSI 27.11.2025).

A multi-layer defence system from the French company Atreyd is also to be deployed, in which a whole swarm of low-cost FPV drones intercepts enemy drones ‘like a flying drone minefield’. With the help of artificial intelligence, a pilot will be able to control 100 drones simultaneously, independently of GPS signals. This exclusively defensive system is intended in particular to protect cities and infrastructure and, in the future, also to intercept glide bombs (↗ Business Insider, 12.11.2025).

At the end of November, the Ukrainian Sting interceptor drone was also successfully deployed against Geran-3 drones (↗ Defence Blog, 30.11.2025). Geran-3 drones can fly faster due to their jet stream propulsion and are evade air defence systems more easily, but Russia has so far used them only sparingly. Ukrainian drone manufacturer Wild Hornets estimates the interception rate of its Sting when used against conventional Geran-2 drones at around 60 to 90%. Another advantage of the Sting interceptor drone is its low production cost of around $2,000 per unit (↗ Defence Express, 20.9.2025).

II. Ukraine's deep precision strike options. An overview

Ukraine must be enabled to attack infrastructure, military airfields, weapons production sites, and supplier production facilities in Russia more effectively. Only in this way can it limit the Russian army's air strikes in terms of quantity and logistics. To do this, Ukraine needs effective and precise long-range weapons (Deep Precision Strike weapons, DPS).

Further developing and scaling the production of domestically produced long-range missiles will be a top priority for Ukraine in 2026. Fabian Hoffmann, an expert in military missile technology at the University of Oslo, sees such missile systems as a “major source of independent strategic leverage” remaining for Ukraine in view of the “growing pressure from the United States to accept an unfavorable negotiated settlement” (↗ Missile Matters, 30.11.2025).

Hoffmann's analysis of the latest Ukrainian air strikes on Russia shows that most of the missiles used had a low explosive charge of less than 100 kg.

Ukrainian manufacturers have now developed a wide range of missile systems. However, equipping them with explosive charges of more than 100 kilograms continues to pose difficulties, according to Hoffmann. Systems such as Flamingo, Sapsan, and Long Neptune have attempted to solve this problem, but “each face uncertainties.” Ukraine, therefore, remains dependent on Western long-range missile systems in the short term.

Capabilities of the Flamingo cruise missile

The FP-5 Flamingo ground-based cruise missile, developed in Ukraine, was tested several times this year. It has a range of 3,000 km and can carry explosive payloads of more than 1,000 kg. However, the FP-5 Flamingo does not use advanced navigation systems such as radar-based TERCOM (Terrain Contour Matching) or DSMAC (Digital Scene Matching Area Correlator) systems, which compare camera images with stored landscape profiles.

Instead, FP-5 Flamingo relies on satellite navigation and the open-source software Ardupilot (↗ IISS, 5.9.2025). Ardupilot is based on conventional dead reckoning, which does not require satellite communication but determines position by calculating speed, time, and flight direction.

The software was also used in Operation Spiderweb in June (↗ golem.de, 3.6.2025), during which the Ukrainian army successfully attacked several Russian airfields. However, in that case, their drones were launched from close range. Over longer distances, dead-reckoning navigation is prone to error. If the FP-5 Flamingo uses satellite communication for navigation, this can easily be electronically disrupted.

The Flamingo also lacks modern guidance systems for a precise final approach to a target. The immense weight of the missile also hinders rapid evasive manoeuvres. The FP-5 Flamingo has only been deployed a few times (↗ Militarnyi, 31.10.2025) and is therefore not shown in the graphic above.

Further Ukrainian domestic missile projects

Ukraine has also developed additional attack systems. The most promising among them is the Long Neptune (R-360L Neptun), a long-range variant of the Neptun anti-ship missile. It has been optimised for land attacks and has a range of 1,000 km. Experts suspect that this missile is equipped with a TERCOM navigation system; possibly even with an adapted seeker head that enables particularly precise target guidance during ground attacks (↗ Missile Matters, 30.11.2025).

Little is known so far about another Ukrainian missile system development, the Sapsan short-range ballistic missile. It is believed to have a range of less than 500 km and a guidance system with a modern Inertial Navigation System (INS).

Options among smaller models

In addition, there is a number of medium-weight missiles produced in Ukraine that can carry explosive charges weighing between 100 and 200 kg. The Bulged Neptune, Bars, and Palianytsia models, for example, have a range of 400 to 700 km. The Ruta cruise missile, produced in Spanish and Dutch factories, has more modern INS seeker heads (↗ Indodefensa, 1.11.2025) and is to be equipped with AI from the US company Shield AI next year. However, Ruta can carry a payload of only up to 150 kg, and the Ukrainian Pekklo mini cruise missile can carry only 70 kg.

Payload remains a limiting factor for Ukrainian-made long-range drones in achieving greater target effectiveness. Hoffmann points out that although many of the drones developed in Ukraine have a range of 200 to 2,000 km, depending on type, and many are equipped with INS and GNSS navigation, they can carry only 25 to 75 kg of explosives.

Another option is converted two-seater aircraft that are operated autonomously without pilots. Here, the maximum payload is 100 kg for a range of 1,000 km. The aircraft-like UJ-22 drone, which flew as far as Moscow in April 2023, is designed to carry only 20 kg of payload.

Western missile types still required

To achieve greater effects, Ukraine therefore remains dependent on Western supplies. In May 2023, the Ukrainian army deployed British Storm Shadow cruise missiles for the first time. From July 2023, Ukraine also received French and later Italian SCALP-EG cruise missiles, which are almost identical to the British model. Thanks to their multi-purpose warheads, they can also successfully attack ‘hardened targets’. Their guidance system is robust and combines INS/GNSS and TERCOM for mid-course guidance with an imaging infrared seeker for terminal guidance. Hoffmann suspects that France, Italy, and the United Kingdom have not limited the range of these cruise missiles, which is around 560 kilometres.

Starting in October 2023, the United States supplied the Ukrainian army with short-range missiles from the ATACMS series, which are controlled either by inertial navigation (INS) or Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). The US supplied models with a range of 185 and up to 300 km. Hoffmann assumes that, by the end of 2025, Ukraine will have no significant stocks of ATACMS, Storm Shadow, or SCALP-EG missiles (↗ Missile Matters, 30.11.2025).

No German government has so far been willing to deliver Taurus cruise missiles (Target Adaptive Unitary and Dispenser Robotic Ubiquity System) to Ukraine. In a roll-call vote in the Bundestag at the request of the Union faction in March 2024 (↗ Bundestag, 14.3.2024), there was no majority in favour of the motion. Nor is there any indication in the statements of the current federal government (↗ Tagesspiegel, 21.5.2025) that Taurus cruise missiles will be supplied or that Ukrainian soldiers will be trained on this system in the foreseeable future (↗ Welt, 30.11.2025).

The serially produced Taurus KEPD-350 model, with a range of around 500 km and a MEPHISTO tandem warhead, is particularly well suited for destroying heavily protected targets. Above all, due to its navigation, the cruise missile has advantages that are currently not available to Ukraine with its own models. The Taurus KEPD-350 has both a GPS receiver shielded against jamming attempts and three additional independent navigation systems that allow autonomous guidance over long distances without satellite communication: an inertial navigation system (INS), terrain reference navigation (TRN), and an image-based navigation system (IBN).

Ukraine needs Deep Precision Strike missiles (DPS) from Western countries. Without new DPS weapons, there is a risk of a capability gap that would put Ukraine at an additional strategic disadvantage in its current precarious military situation. If, on the other hand, Ukraine has sufficient means to exert sustained and effective pressure on Russia, this strengthens its negotiating position and increases the chance of ending the war with a lasting peace.

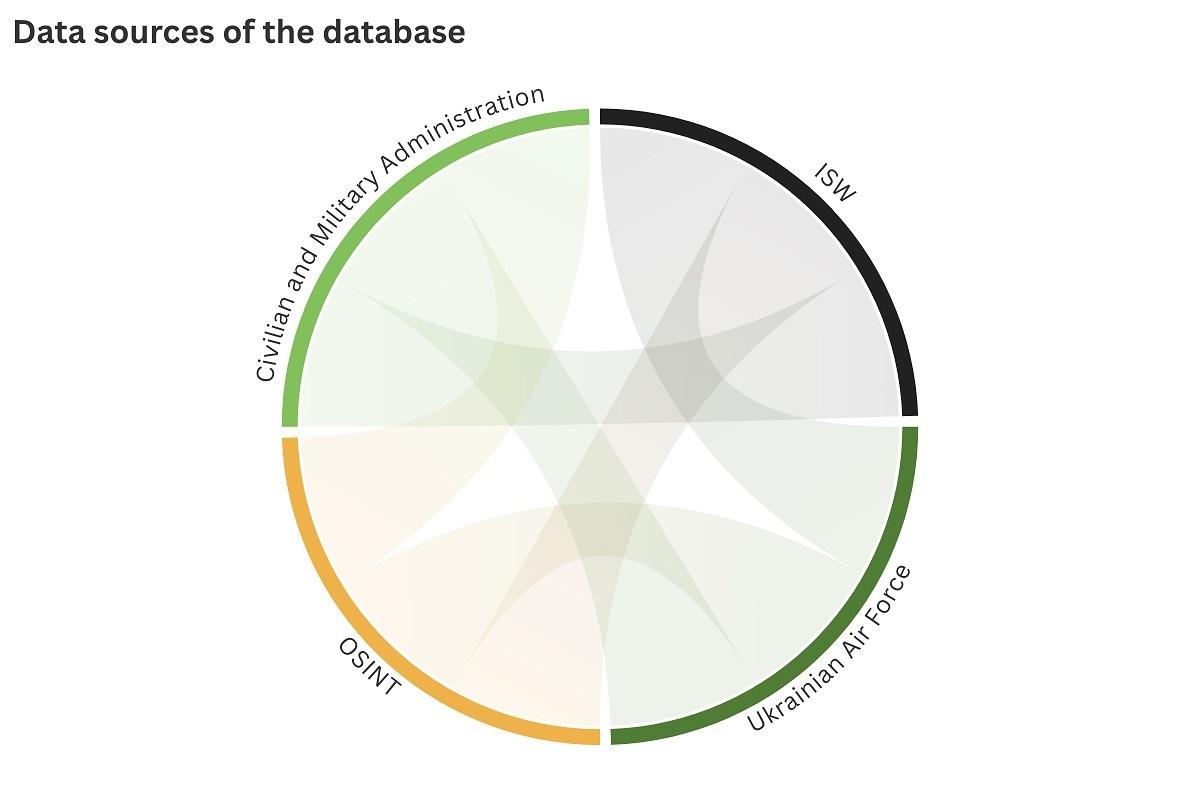

Method

The air strike database is regularly cross-referenced with daily reports from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) in Washington (↗ ISW).

The launch records originate from the Ukrainian Air Force reports (↗ KPSZSU), and data on regional targets and damage—if available—is supplemented with civilian and military administration sources.

These figures are further verified using additional OSINT sources and are considered highly reliable.

Accurately quantifying air strike damage during an active war is inherently challenging. Providing overly precise information could aid Russian military planning, which is why certain reporting restrictions apply (↗ Expro, 2.1.2025).

Consequently, this analysis focuses on attack patterns and dynamics rather than detailed damage assessments.

With over 39 months of data and around 70,000 documented attacks, robust trends have emerged. Monthly missile counts are approximate values, as irregularities have been noted in Ukraine’s reporting system. Discrepancies with other OSINT sources remain within a 10 % margin, often below 3 %.

A comparison with the missile and drones assessment by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington over a period of more than two years shows a deviation of only 1.6 % (↗ CSIS).

For attacks lacking definitive quantification, the lowest plausible estimates have been used. Due to possible underreporting in high-intensity phases, actual interception rates may be slightly higher, with an estimated deviation of less than 5 %.

About the Author

Marcus Welsch is a freelance analyst, documentary filmmaker, and publicist.

Since 2014, he has specialized in OSINT journalism and data analysis, focusing on the Russian war against Ukraine, military and foreign policy issues, and the German public discourse.

In cooperation with Kyiv Dialogue, he has conducted research and panel discussions on Western sanctions policy since 2023.

Since 2015, he has been running the data and analysis platform ↗ Perspectus Analytics.

About Kyiv Dialogue

Kyiv Dialogue is an independent civil society platform dedicated to fostering dialogue between Ukraine and Germany.

Founded in 2005 as an international conference format addressing social and political issues, it has moved to support civil society initiatives aimed at strengthening local democracy in Ukraine since 2014.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the focus has shifted to social resilience, cohesion, and security policy—including military support for Ukraine and Western sanctions policy.

Kyiv Dialogue is a program of the European Exchange gGmbH.

CONTACT

Kyiv Dialogue

c/o Europäischer Austausch gGmbH Erkelenzdamm 59, D-10999 Berlin +49 30 616 71 464-0 info@kyiv-dialogue.org www.kyiv-dialogue.org

Konrad Adenauer Foundation Ukraine

Bogomoltsja St. 5, Wh. 1, 01024 Kyiv / Ukraine

+38 044 4927443 office.kyiv@kas.de

www.kas.de/de/web/ukraine

You need to sign in in order to comment.