Multi-speed membership decline

Tracking party membership across Europe is a challenging task. Researchers typically rely on two types of data: surveys asking individuals if they belong to a party, and official figures provided by parties or other official agencies. Neither method is perfect, but official reports allow to compare trends over time and across parties within countries. Two key sources are the MAPP dataset, which covers 397 parties in 31 countries from 1946 to 2014 , and the Political Party Database (PPDB), which includes 288 parties in 51 countries (2016-2019) . For comparison purposes across parties and countries, it is common to calculate the membership ratio (M/E), that is, the number of members a party has as a proportion of the country’s total electorate.

Party membership has been diagnosed as in decline in most European democracies ever since scholars started collecting party membership figures. While this observation is true, it also must be nuanced:

- Starting point matters: Most studies begin in 1945, a time of exceptionally high membership. Before World War II, large membership-based parties were rare. The observed decline may have brought parties back to where they were pre-war.

- Better data quality: Modern technology makes it easier to manage and update membership lists, to check identities and tracing payment of fees. Membership decline may partly be linked to the improvement of data quality.

- Party differences: Accounts of national declines often reflect sharp drops in a few major parties, like Social Democrats or Conservatives.

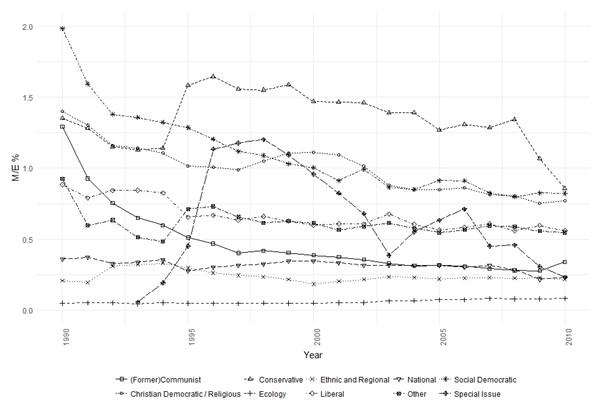

To get a clearer picture, we focus on data from 1990 onwards. Figure 1 groups parties by party families and presents the trend in their average membership ratio between 1990 and 2010. Social Democratic, Conservative, and Christian Democratic parties – all (former) mass-membership types of parties – saw the steepest declines. For example, the Danish Conservatives lost 66% of their members, and the British Conservatives lost 84%. This trend continued into the 2010s. Table 1 shows that these three party families have gone further down in membership ratios by the end of the 2010s.

Figure 1. Party membership ratio (M/E) by party family, 1990–2010

Other party families, like the (former)Communists, the Liberals, the Nationals, and the Ethnic/Regional parties, have faced a stabilisation of their membership between 1990 and 2010. These parties have, however, faced some decline by the end of the 2010s, except for the Nationals, a party family that integrates (populist) radical right parties (Table 1).

Table 1. Party membership ratio (M/E) by party family, 2017–2018 (PPDB)

| Party Family | Membership ratio 2017-2018 |

| Former)Communist / Radical Left (16) | 0,29 |

|

Christian Democrat/Religious (14) |

0,44 |

| Conservative (20) | 0,43 |

|

Ethnic and Regional (15) |

0,15 |

| Green (15) | 0,10 |

| Liberal (25) | 0,39 |

|

National / (Populist) Radical Right (23) |

0,32 |

|

Other / Special Issue (14) |

0,44 |

|

Social Democrat (27) |

0,61 |

Lastly, other families like the Greens, special issue parties (such as farmers and agrarian parties, senior, women, or animal parties), and parties outside these classic party families, have even seen partial growth in their membership. The growth of the Greens has continued by the end of the 2010s (Table 1).

However, their baseline was much lower than traditional membership-based parties, and their gains do not make up for the losses of the others, which explains the overall trend of decline at the national level.

Why is party membership on the decline?

Membership decline over time is often attributed to post-industrialisation of societies, which come with shifts in participation repertoires and the emergence of alternative modes of political participation. These shifts are linked to higher levels of education and changes in values generating atomised participation to the detriment of group-based memberships. Yet this view is partly challenged at the individual level, as studies stress the positive impact of education on the likelihood to join parties.

Membership variation across countries is often attributed to differences in institutional settings. Presidential or hybrid regimes yield more members than parliamentary democracies, as do smaller, decentralised polities, and the existence of party laws incentivising for membership. Also, government participation that offers a patronage boost to parties, brings more members. Conversely, high fragmentation of the party system brings fewer members to individual parties in a limited market.

Yet parties are not mere victims of societal changes and institutional designs. Research has shown that the way they conceive and regulate affiliation matters too.

Parties offering alternative affiliation options (supporter, sympathiser) have fewer (yet more active) members. Alternative affiliation options offer a ‘cheaper’ route for citizens who want to connect with parties without bearing the costs of membership engagement, leaving only the more committed citizens to join. About one third of European parties offer such an alternative option, with the Social Democrats and the Greens leading the way, the Conservatives, Christian-Democrates and Radical Right following the general average, and the Radical Left and Liberals making less use of this option.

How parties allow their members to participate in the decision-making process matters too. Granting members higher benefits, like participating in leadership and candidate selection processes or manifesto formulation, has no clear impact on the number of members joining, but is linked to having less active members, maybe because these citizens joined for one ‘big’ decision and not really to get involved on a day-to-day basis. Conversely, the cost of joining does not really matter. The level of financial costs (membership fee) or procedural costs to join (minimum age, probation period, sponsorship) does not impact membership figures, showing a form of disconnect between costs and the act of joining.

Research also shows that parties that grant more place for the representation of sub-groups in their organisation, such as youth wings, women or senior groups, have more members, because they build stronger linkage and can rely on more diverse recruitment pools. Being able to rely on a network of recruiters matters. In this regard, some parties are caught in a spiral of decline. With membership numbers in decline and local branches getting older, breaking up the declining trend and diversifying membership recruitment proves difficult, as recruitment often operates via homophily. Developing recruitment channels via specialized groups can compensate for that.

Parties are therefore not powerless when it comes to membership and can tailor their affiliation rules to the type of linkage they would like to develop with citizens.

Why should parties care about their membership levels?

While some argue that supporters or digital followers can replace traditional members, the evidence suggests otherwise. Parties can rely on supporters and digital activists to improve their image, or provide them with new, more diverse profiles (women, youth, less educated). However, recruiting such affiliates does not extend the ideological diversity within parties and does not necessarily bring in new ideas. And there is a limit to the extent to which supporters, digital activists, and members bring equal benefits to parties. Members are unique, essential resources comes election time. Members tend to be more involved in campaigns than party supporters and digital activists, especially when it comes to intensive tasks. Furthermore, members bring supporters and other types of affiliates, as research shows that a large number of members in a district is a pre-condition for higher supporter activity, members acting as recruiters via their everyday contacts in the community. Members also bring benefits to party organizations outside election time. Membership decline induces parties to employ more staff, to spend more, to be more reliant on state subsidies, and to reduce their local anchorage.

Ultimately, research shows how parties that build strong grassroots organizations – local anchorage, organisation outside the parliamentary party and the party leadership-perform better at the polls. Within a party, active local branches yield better electoral performances. Organisational strength also brings parties a higher chance of survival. In this light, members still constitute a distinct and unique asset for parties, especially during elections and in building strong local networks. They campaign, recruit, and help shape parties’ identities.

This link between membership, organisational strength, and electoral stability also help understand the changes in European party systems. Weak grassroots anchorage means that parties build weaker partisan identities and are more prone to electoral volatility. Membership decline in mass-membership parties has been linked to their declining electoral performances. Conversely, memberships in national right-wing populist have been growing, to the point that some call these parties the new mass parties and have been feeding their growing electoral performances. This success can not only be attributed to continuous online campaign; while winning the air war matters, it is only in combination with a successful ground war that parties can establish themselves in the long run.

As democracies face new challenges, rethinking how parties engage with citizens, diversifying their linkage without losing the value of committed members, will be key to staying electorally and politically relevant.

Higher levels of party membership are also related to higher levels of trust and identification in parties – and vice-versa. Investing in building strong membership-based organisation may be essential if parties want to remain legitimate actors in representative systems.

Emilie van Haute is a professor at the Department of Political Science at the Université libre de Bruxelles.

References:

- Achury S., Scarrow S., Kosiara-Pedersen S., van Haute E. (2018), “The consequences of membership incentives: Do greater political benefits attract different kinds of members?”, Party Politics, 26(1), S. 56-68.

- Albertazzi D., van Kessel S., Favero A., Hatakka N., Sijstermans J., Zulianello M. (2025). Populist Radical Right Parties in Action. The Survival of the Mass Party. Oxford University Press.

- Fisher J., Cutts D., Fieldhouse E., Rottweiler B. (2017), “District-level Explanations for Supporter Involvement in Political Parties”, Party Politics, 24(6), S. 743–754.

- Gauja A., Kosiara-Pedersen K., Weissenbach K. (2024), “Party membership and affiliation: Realizing party linkage and community in the twenty-first century”, Party Politics, 31(2), S. 207-216.

- Kölln A.-K. (2016), “Party Membership in Europe. Testing Party-level Explanations of Decline”, Party Politics, 22(4), S. 465–477.

- Kosiara-Pedersen K., van Haute E., Scarrow S. (2025), “Social media partisans vs. party members: political affiliation in a digital age”, West European Politics.

- Mair P., van Biezen I. (2001), “Party Membership in Twenty European Democracies: 1980–2000”, Party Politics 7 (1), S. 5–21.

- Paulis E., van Haute E. (2022), “You Will Never Participate Alone. Personal Networks and Political Participation in Belgium”, Political Science Research Exchange 3(1).

- Poguntke T., Scarrow S., Webb P., Allern E.H., Aylott N., van Biezen I., Calossi E., Costa Lobo M., Cross W., Deschouwer K., Enyedi Z., Fabre E., Farrell D.M., Gauja A., Pizzimenti E., Kopecky P., Koole R., Müller W.C., Kosiara-Pedersen K., Rahat G., Szczerbiak A., van Haute E., Verge T. (2016). “Party rules, party resources and the politics of parliamentary democracies: How parties organize in the 21st century”, Party Politics, 22(6), S.661-678.

- Scarrow S., Webb P., Poguntke T. (2017). Organizing Political Parties. Representation, Participation, and Power. Oxford University Press.

- Scarrow S. (1996), Parties and their Members. Oxford University Press.

- Sierens V., van Haute E., Paulis E. (2022), “Jumping on the Bandwagon? Explaining Fluctuations in Party Membership Levels in Europe”, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties 33(2): 300–321.

- Van Biezen I., Mair P., Poguntke T. (2012), “Going, Going,…Gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe”, European Journal of Political Research, 51 (1), S. .24–56.

- Van Haute E., Gauja A. (eds) (2015), Party Members and Activists. Routledge.

- Van Haute E., Ribeiro P.F. (2022), “Country or Party? Variations in Party Membership around the Globe”, European Political Science Review, 14(3), S. 281-295.

- Van Haute E., Paulis E., Sierens V. (2017), “Assessing party membership figures: the MAPP dataset”, European Political Science 17(3), S.366-377.

- Webb P., Poletti M., Bale T. (2017), “So who Really Does the Donkey Work in ‘Multispeed Membership Parties’? Comparing the Election Campaign Activity of Party Members and Party Supporters”, Electoral Studies, 46, S.64–74.

- Whiteley P. (2011), “Is the Party Over? The Decline of Party Activism and Membership Across the Democratic World”, Party Politics 17(1), S.21–44.

"Geschichtsbewusst" reflects a range of political perspectives. The content of an essay reflects the opinion of the author, but not necessarily that of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.