SUMMARY

- In December, Russia deployed 5,131 drones against Ukrainian cities and civilian targets (6% fewer than in the previous month), as well as 120 cruise missiles and 57 ballistic missiles. For the first time, the use of an Iskander-1000 missile was reported. Medium-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) of the Oreshnik type are expected to be stationed in Belarus.

- The interception rate for drones fell to 81% (previous month: 84%). In December, 987 drones could not be intercepted (previous month: 844). Interception rates for ballistic missiles and cruise missiles changed little: approximately 25% of ballistic missiles were intercepted, and an average of 85% of cruise missiles.

- In total, 1,052 drones and missiles were not intercepted in December (previous month: 996). Due to the lower number of missiles with larger warheads, the total amount of unintercepted payload continued to decline.

- Heavy attacks on Ukraine’s power grid led to widespread power outages and restrictions on energy use. The Odesa region in particular was heavily affected in December. East of the Dnipro River, problems with electricity supply intensified. Infrastructure in the gas and oil sector as well as railway lines was also severely damaged.

REVIEW OF 2025

- In 2025, the Russian army carried out approximately 56,700 air attacks, primarily using long-range drones (96% of all attacks), against civilian targets in Ukraine — more than four times as many as in 2024 (13,300). In 15 nights in 2025, attacks involving more than 500 drones were recorded. Drone defense remained the greatest challenge for the Ukrainian Air Force. The interception rate for long-range drones fell from 98% in February to as low as 80% in October.

- Ukraine was able to restrict Russian drone production through targeted strikes on factories and supplier companies. From August 2025 onward, the number of Russian long-range drones deployed declined steadily. China remains the most important supporter of Russia’s drone production.

OUTLOOK FOR 2026

- In 2026, there is reason to fear that modified armament and control systems on Russian drones could pose a greater threat. This can be countered by financing the production of air defense systems in Ukraine.

- According to the British think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), Russia will come under increasing pressure in 2026 and will therefore attempt to escalate the war in hybrid form. This is likely to particularly affect populations in front-line regions and in the port city of Odesa.

- A strategically sound and effective response to the threat posed by Russia is the targeted disruption of the modernization and production of Russian air defense systems. In addition, European NATO states should supply Ukraine with highly effective long-range precision weapons, enabling deep precision strikes on Russian territory.

SITUATION IN DECEMBER – ANALYSIS AND TRENDS

In December, the Russian army attacked Ukrainian cities and civilian targets with 5,131 drones (6% fewer than in the previous month). This corresponds to an average of 166 drones per night. These figures are based on an evaluation of reports by the Ukrainian Air Force Command (KPSZSU). Attacks on critical infrastructure targets often consisted of several consecutive waves, frequently involving extremely large numbers of drones.

Ukrainian drone air defence achieved a slightly lower interception rate of 81% in December (November: 84%). In total, 987 drones could not be intercepted (November: 884). The share of decoy drones used in the attacks (mostly Gerbera type) declined slightly to 38%. Russia most frequently deployed long-range Shahed-136/Geran-2 drones.

The number of Russian cruise missiles deployed remained largely unchanged at 120 (previous month: 114). The number of ballistic missiles nearly halved to 57 (previous month: 106). For the first time, the possible use of an Iskander-1000 missile was reported — a new variant of the Iskander-M ballistic missile with a range of up to 1,300 km and a warhead weighing 200–300 kg (↗ ISW, 18.12.2025). This allows targets at significantly greater distances to be attacked compared to the standard Iskander-M variant, which is limited to a range of 500 km.

The interception rate for ballistic missiles declined slightly to around 25% (previous month: 30%). For cruise missiles, the average interception rate was 85% (previous month: 80%), although monthly values vary between 60% and 90% depending on missile type.

In total, 1,052 drones and missiles were not intercepted in December. Of these, 130 missed their targets, according to KPSZSU reports. The remaining 920 drones and missiles struck a total of 420 different targets.

Interception rates of Russian drones and missiles

The actual destructive potential of attacks that were not intercepted is illustrated by the total amount of unintercepted payload, i.e., the combined type-specific explosive payload of all drones and missiles. In December, this amounted to 60,935 kg of explosives.

This represents a decrease of 12% compared to November (69,540 kg), primarily because the share of missiles and cruise missiles with greater destructive power among the non-intercepted drones and missiles declined. Nevertheless, this remains the third-highest value of the year (peak in October: 93,730 kg).

CONTINUED ATTACKS ON INFRASTRUCTURE AND CIVILIANS

In December, Russian attacks were even more strongly concentrated on a few regions, primarily Odesa, followed by Kharkiv and Dnipro regions. Front-line areas were also subjected to intensive use of drones, missiles, and glide bombs. Compared to the previous month, the Kyiv region was targeted twice as often (↗ ISW daily reports).

In the Odesa region, the Russian army repeatedly targeted civilians in addition to transport infrastructure. Alongside Geran-2 drones, an Iskander missile with cluster munitions was used against workers repairing the Majaky Bridge near Odesa (↗ ISW, 19.12.2025).There were also renewed targeted double-tap strikes on emergency services. Hospitals were attacked as well: on December 10 in Kherson, and on January 5 in Kyiv (↗ Kyiv Independent, 5.1.2026).

Major attacks on the Ukrainian energy system, including on December 6, 13, and 18, caused severe and lasting damage. In several regions, electricity was completely cut off for private households, in some cases also for industrial facilities. Additional energy-saving measures were introduced, such as restrictions on exterior and street lighting (↗ Dixi-Group, 15.12.2025). The list of critical infrastructure facilities exempt from power outages was shortened. Freed-up capacity of approximately 800 megawatts is to be redistributed to private households (↗ Dixi-Group, 23.12.2025).

As a result of attacks on the Kyiv region on the night of December 27, nearly 600,000 people were left without electricity. Since October, the Russian army has deliberately targeted electricity grids to disrupt the redistribution of power from western Ukraine, where most electricity is generated. If successful, this would effectively split Ukraine in two

(↗ Washington Post, 15.12.2025). East of the Dnipro River in particular, the situation deteriorated toward the end of December to the extent that neither the timing nor the duration of necessary power outages could be planned (↗ ASTRA press, 30.12.2025).

According to the Ukrainian oil and gas producer Ukrnafta, Russian forces attacked its production facilities with nearly 100 attack drones between December 22 and 24 alone. The state railway company Ukrzaliznytsia estimates damage to the rail network since 2022 at USD 5.8 billion, with more than 1,100 attacks on its infrastructure recorded in 2025 alone (↗ WSJ, 31.12.2025).

BACKGROUND – ANNUAL REVIEW AND OUTLOOK FOR 2026

ATTACKS ON CIVILIAN TARGETS QUADRUPLED

In 2025, there were around 56,700 air attacks using drones, missiles, and cruise missiles against civilian targets in Ukraine — more than four times as many as in 2024 (13,300). According to the Ukrainian Air Force, 8,424 of these attacks could not be intercepted, primarily due to the massive increase in the use of Shahed drones. The threat posed by ballistic missiles remained roughly unchanged.

In total, approximately 54,700 drone attacks were recorded in 2025, compared to 11,000 in the previous year. This sharp increase, which fundamentally changed the air war, had already become apparent in August 2024. At the start of the Russian air war in autumn 2022, only 30% of all deployed aerial weapons were drones; today, the figure stands at 96%. Until summer 2024, the monthly peak was 590 drone attacks.

Terror against the civilian population

By July 2025, there were already 6,300 drone attacks within a single month. As a result, the intensity of night-long terror against the civilian population also increased. In the past year alone, more than 500 drones were recorded on 15 individual nights. The largest attack to date, involving 810 drones and 13 ballistic missiles, took place on the night of September 6–7, 2025.

The intensity and intervals of drone attacks have also changed. Until April 2023, air attacks occurred on two to seven nights per month. From 2024 onward, Russia attacked civilian targets in Ukraine almost daily — increasingly at night over time, to place the greatest possible strain on civil society.

Застосовані Росією засоби повітряного нападу по місяцях, січень 2024-грудень 2025 рр.

Russian drones and missiles deployed per month, January 2024–December 2025

CHALLENGE FOR AIR DEFENCE

The Ukrainian Air Force has continuously optimized its drone defense over the past two years. In 2025, however, performance deteriorated dramatically: the high drone interception rate of 98% in February 2025 fell to 80% by October. While only 90 drones were not intercepted in February, this figure rose to more than 1,000 in October (↗ see Monitor Vol. X).

Interception rates for cruise missiles and ballistic missiles developed very dynamically in 2025 and depended heavily on attack specifics as well as the deployment locations of air defense systems. Modifications to Iskander-M missiles (9M723) further complicated interception (↗ RUSI, 18.11.2025).

From March 2025 onward, the availability of interceptor missiles became a major challenge for Ukrainian air defence due to fluctuating U.S. policy toward Ukraine (↗ see Monitor Vol. V), and the generally limited production capacities of the Patriot system, which is the key system for intercepting ballistic missiles (↗ see Monitor Vol. X).

Interception rates for ballistic missiles fluctuated between 5% and 50% (annual average approx. 25%, previous year approx. 20%), while cruise missiles were consistently intercepted at monthly rates between 65% and 90%, thanks to support from Mirage 2000 and F-16 interceptor aircraft. Overall, airborne air defence remains effective: since summer 2024 alone, F-16s have intercepted more than 1,300 aerial attacks (↗ KPSZSU, 19.11.2025).

ENERGY SUPPLY IN FRONT-LINE REGIONS IN FOCUS

As in the previous three winters of the war, the primary objective of the Russian military leadership in 2025 remained the destruction of Ukraine’s energy grid. By concentrating attacks on a small number of targets and oblasts, this strategy became increasingly effective. From October to December 2025, there were eight massive missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure, with devastating effects. Electricity imports to Ukraine rose by 54% in December (↗ open4business, 8.1.2026).

Over the course of 2025, the city and region of Kharkiv were subjected to air attacks on at least 250 days, followed by the oblasts of Dnipropetrovsk, Sumy, Kyiv, and Odesa. Russia is deliberately targeting regions close to the front line in an attempt to bring civilian life to a collapse. The oblasts of Chernihiv, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia were attacked up to 15 times more frequently than regions in western Ukraine; central Ukrainian regions such as Poltava, Mykolaiv, and Cherkasy were also heavily affected.

Number of days with damage reports by region, January–December 2025

RUSSIAN PRODUCTION CAPACITIES

With the support of its allies, Russia was able to increase weapons production over the past year. Key components originate from the People’s Republic of China, ballistic missiles of the KN-23 type as well as labor from North Korea (↗ ISW, 31.12.2025).

Nevertheless, Russia fell short of its own production targets. According to information from the Ukrainian military intelligence service HUR, the Russian military leadership planned to produce approximately 79,700 long-range drones in 2025 (↗ see Monitor Vol. VIII).

There are no detailed data on how Russian drone production actually developed in recent months. Since August, however, the number of deployed drones has clearly declined.

SUCCESSFUL UKRAINIAN STRIKES

The decline in Russian drone production is likely attributable to Ukrainian attacks on supplier companies within Russia (↗ Militarnyi, 1.9.2025).

These included drone attacks in summer 2025 on the Kupol plants in Izhevsk — one of Russia’s largest defense enterprises (↗ ASTRA press, 2.7.2025) — on a drone storage facility (↗ Dnipro OSINT, 9.8.2025)[5] as well as on a ship in the Caspian Sea on August 14 that was intended to deliver components for drone production from Iran. The chemical plant in Krasnozavodsk in Moscow Oblast, which manufactures thermobaric warheads for attack drones, was also damaged on July 7, 2025 (↗ OSINT Project CyberBoroshno, 13.7.2025).

If Ukraine continues to succeed in weakening strategically important supplier companies through air strikes, while at the same time further developing its own drone air defence and rapidly scaling up production, the drone war may no longer represent the greatest challenge in Ukraine’s rear areas in 2026.

However, it will also be decisive whether Russia is able to produce the next generation of Geran-3 drones (a further development of the Iranian Shahed-238 drone) with turbojet engines in larger numbers. This drone reaches a flight speed of up to 600 km/h and is therefore more than twice as fast as the Geran-2 drone most frequently deployed in 2025. The advanced model is believed to have a range of approximately 1,000 km (some sources even assume up to 2,000 km) and can fly at altitudes of up to 9,000 meters (↗ Militarnyi, 31.10.2025).

At present, however, Russia is still unable to manufacture the engine for this drone type in large quantities. In 2025, only isolated deployments of Geran-3 drones were recorded, most recently during attacks on Chernihiv on December 24.

TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN LONG-RANGE DRONES

In October 2025, long-range drones were observed attacking moving trains and using integrated night-vision cameras and radio-control functions. This new technology involving optical guidance had already been identified in June in a downed Shahed drone near Sumy. An onboard mini-computer (Nvidia Jetson Orin) enables high-performance video processing and autonomous target acquisition. The technology also suggests the use of “radio bridges” to ground-based repeaters near the target. The operational radius of these guided drones is estimated at approximately 200 km (↗ Militarnyi, 1.10.2025).

The Russian army also repeatedly uses Belarusian territory to directly control drones and to bypass Ukrainian air defence — for example during an attack on a freight train in the western Ukrainian city of Kovel (↗ RBC, 26.12.2025). In the air war of 2026, Belarus is therefore likely to play an increasingly important role as an approach corridor. This will also affect NATO airspace surveillance in Poland.

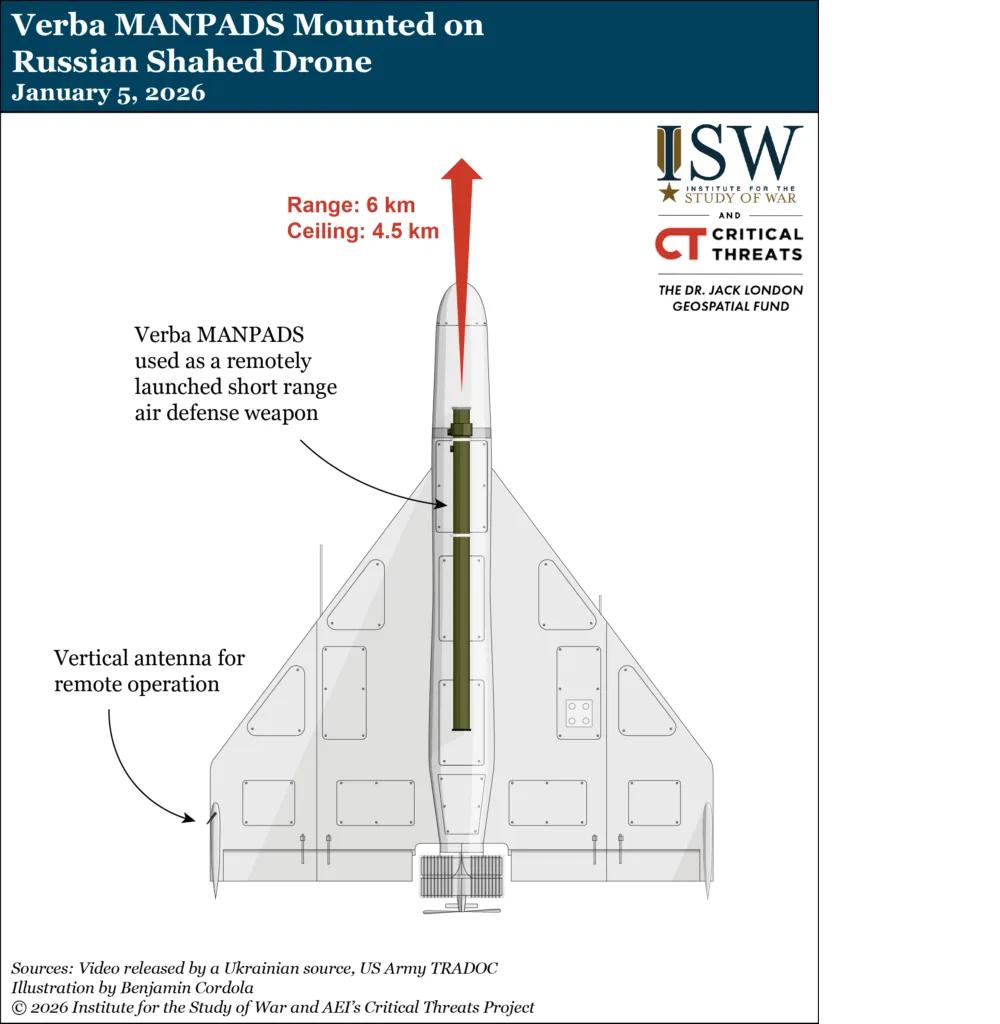

In November, Geran-2 drones were observed that were additionally armed with rockets

(↗ see Monitor Vol. XI). There is concern that modified armament could double the amount of explosive payload carried. On January 4, a Russian MANPADS (man-portable air defense system) mounted on a downed Shahed drone was discovered, capable of engaging helicopters and aircraft (↗ Militarnyi, 4.1.2026).

Ukrainian interceptor drones can circumvent the fixed firing orientation of such MANPADS by approaching from the rear. However, this would require Ukraine’s forward interception lines to be equipped with a sufficient number of additional interceptor drones.

To counter this threat effectively, Western partners must support both the scaling up of the production of new drone air defense systems in Ukraine (↗ see Monitor Vol. XI) and their further development, including electronic components and sensors.

In addition, Ukrainian air defence must be better equipped (↗ see Monitor Vol. X). This includes deploying Western-built trainer aircraft against Geran-3 drones and supplying the Ukrainian armed forces with gun systems capable of reaching the flight altitude of the new drone types (↗ see Monitor Vol. VII).

WESTERN COMPONENTS IN RUSSIAN WEAPONS

Electronic components from Swiss companies were found in the Russian MANPADS mentioned above (↗ Militarnyi, 4.1.2026). A wide range of Western components continues to be installed in numerous other Russian attack weapons such as drones, Kalibr cruise missiles, and Iskander missiles (↗ SFR, 26.2.2025, Swiss Info, 9.4.2023) as already documented in detail by the Kyiv School of Economics in summer 2023 (↗ KSE, 23.8.2023). Ukrainian NGOs such as State Watch regularly report on current developments through projects like “Trap Aggressor” (↗ Trap Aggressor Project, 9.12.2025).

To manufacture Geran drones, for example, Russian factories in the Alabuga special economic zone require 294 different components that do not originate in Russia. 40% come from China and Taiwan; 34% of components are supplied by companies from the United States (↗ Militarnyi, 8.10.2025). The Ukrainian military intelligence service HUR publishes detailed lists of components used in Russian drone models. These also name components from the German companies Infineon Technologies and Bosch (↗ GUR, Geran-3-Komponenten).

Without Western components, Russia cannot build modern attack weapons, even though it is attempting to replace them with Chinese parts. China also plays a central role as an intermediary supplier of Western components in Russian weapons production.

RUSSIAN MISSILES: A THREAT TO EUROPE

In the first two years of the air war against Ukraine, Russia relied primarily on cruise missiles drawn from Soviet-era stockpiles, including Kh-22 missiles. Originally developed to target aircraft carriers, these cruise missiles often struck their targets with very poor accuracy, resulting in additional civilian casualties.

As leaked documents from the Ukrainian military intelligence service HUR show (↗ see Monitor Vol. X), Russia has increasingly focused on the new production of more modern cruise missiles such as the Kh-101, Kalibr, and Iskander-K. These accounted for the majority of cruise missiles used in the past year. Shorter-range models were also employed. In total, approximately 1,300 cruise missiles were used in 2025. In addition, Russia deployed around 600 ballistic missiles of the Iskander-M and Kh-47M2 (Kinzhal) types.

The annual total of cruise missiles and ballistic missiles that Russia used against civilian targets in Ukraine in 2025 amounts to approximately 2,000. In addition to the types mentioned above, this figure includes S-300 and S-400 air defense missile systems deployed near the front line (around 100 units).

Russia has further expanded its production capacity for ballistic missiles. This represents a threat not only to Ukraine, but also to European NATO countries. The problem is compounded by the fact that European states neither possess sufficient quantities of suitable interception systems and interceptor missiles nor are able to produce them in the coming years

(↗ see Monitor Vol. VIII).

Over the past year, varying figures regarding remaining stockpiles and production capacities of the Russian military have become public. The leaked Russian procurement data largely corresponds with the number of cruise missiles used in 2025.

Russia is likely holding back ballistic missiles. Current stockpiles are estimated to be close to 800 Iskander-M and Kinzhal missiles (as of the end of 2025). The leaked procurement documents also list planned quantities for the Zircon hypersonic missile and the new Iskander-1000 model, which appeared only twice in KPSZSU reports in 2025 (↗ see Monitor Vol. X).

It is expected that Russia will deploy Oreshnik-type intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) in eastern Belarus. This is suggested by statements from senior Belarusian politicians and satellite imagery showing the reconstruction and rail connection of a former airfield near the Russian border (↗ Reuters, 31.12.2025). On the night of January 9, 2026, this missile type was again used in attacks on an aircraft maintenance facility in Lviv (↗ see Monitor Vol. II)

WHAT TO EXPECT IN 2026?

In an outlook for 2026, the British Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) notes that since the withdrawal from Kyiv in April 2022, Russia has failed to achieve four of its five strategic objectives: “political subjugation, economic sustainability, regime stability and international standing.” Only with regard to territorial control of the partially annexed areas in eastern Ukraine has Putin achieved a Pyrrhic victory. “But a declining power is often more dangerous than a rising one. Facing an economic spiral and depleted conventional forces, Vladimir Putin is entering a window of maximum danger. We must prepare not for a resurgent Russia but for a desperate one: 2026 will be the year of hybrid escalation.” (↗ RUSI, 19.12.2025)

Ukrainian regions close to the front line are likely to be subjected to even more intense attacks in the coming year. These areas are not only exposed to glide-bomb attacks (↗ see Monitor Vol. X) but, due to increasing ranges, also increasingly to FPV drones (↗ see Monitor Vol. XI). There is reason to fear that the Odesa region will become a stronger focus of the Russian air war. In December, it was subjected to the heaviest shelling in four years (↗ New York Times, 25.12.2025), including air attacks on ports in Odesa that handle 90% of Ukraine’s agricultural exports (↗Wall Street Journal, 31.12.2025). In addition, the region has only limited electricity production capacity and is dependent on external energy supplies.

RECOMMENDATIONS

NEW STRATEGIC OPTIONS FOR CONTAINING RUSSIA

Russia continues to produce high-performance air defense systems and urgently requires them to repel Ukrainian strikes on the defense industry and the oil sector, and to stabilize the front. In the medium to long term, these systems also pose a threat to NATO air forces and conventional deterrence in Europe.

A study by British and Ukrainian experts shows that Russia’s centralized manufacturing processes contain significant vulnerabilities. These could be exploited, for example, to disrupt the modernization of microelectronics production. Interrupting supply chains would also significantly impair Russian arms production. Materials such as beryllium oxide ceramics, which are essential for radar technology, are imported from Kazakhstan (↗ RUSI, 12.12.2025).

DISRUPT THE PRODUCTION OF RUSSIAN AIR DEFENCE

Russia is also dependent on Western-made measuring equipment and calibration tools for quality control. Stricter enforcement of sanctions and export controls — including against manufacturers of machine tools (especially CNC machines) — could restrict the production and repair of Russian air defense systems. The authors of the study also recommend: “Exploit software critical to the design and development of Russian air defences through cyber intrusions, to gain information to enable the compromise of air defence complexes and disrupt production processes.”

The defense industry in Tula, located just 350 km from the Ukrainian border, is among the most vulnerable production sites in Russia’s arms industry (↗ RUSI, 12.12.2025).

In 2025 alone, fifteen attempted Ukrainian attacks on this site were documented, most recently on December 25, 2025.

Russia is currently consuming more interceptor missiles than it can produce. Any further impairment of these production capacities would place significant pressure on Russian military strategy and the planning of future operations.

INCREASE MILITARY PRESSURE

To more effectively constrain Russia’s air war against Ukraine in 2026, it would therefore be necessary to increase attacks on strategic targets within Russia that are central to maintaining its military capabilities.

Western partners should therefore supply Ukraine with more advanced weapons systems for long-range air strikes: deep precision strikes (DPS) (↗ see Monitor Vol. XI).

Only through effective military pressure will the Kremlin alter its strategic calculations and become willing to engage in serious negotiations. This not only serves the defense of Ukraine, but also increases the security of Europe as a whole and is a central prerequisite for a lasting peace in Europe.

SUBSTANTIALLY IMPROVE SUPPORT FOR UKRAINIAN DEFENCE

It is not foreseeable when the war in Ukraine will end. In light of the Russian threat to Europe, a new overarching strategy is required that also accounts for reduced U.S. support. To prevent further wars, Ukraine must not only possess significantly improved defensive capabilities in 2026, but also be able to exert tangible pressure on Russia. Substantially increased support for Ukraine is, in the long term, less costly for Europe than the consequences of a Russian victory — particularly with regard to expected refugee movements and the defense of Northern and Eastern Europe (↗ NUPI, 11.11.2025).

A more detailed analysis will follow in the next issue of the Monitor.

Method

The air strike database is regularly cross-referenced with daily reports from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) in Washington (↗ ISW).

The launch records originate from the Ukrainian Air Force reports (↗ KPSZSU), and data on regional targets and damage—if available—is supplemented with civilian and military administration sources.

These figures are further verified using additional OSINT sources and are considered highly reliable.

Accurately quantifying air strike damage during an active war is inherently challenging. Providing overly precise information could aid Russian military planning, which is why certain reporting restrictions apply (↗ Expro, 2.1.2025).

Consequently, this analysis focuses on attack patterns and dynamics rather than detailed damage assessments.

With over 40 months of data and around 75,300 documented attacks, robust trends have emerged. Monthly missile counts are approximate values, as irregularities have been noted in Ukraine’s reporting system. Discrepancies with other OSINT sources remain within a 10 % margin, often below 3 %.

A comparison with the missile and drones assessment by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington over a period of more than two years shows a deviation of only 1.6 % (↗ CSIS).

For attacks lacking definitive quantification, the lowest plausible estimates have been used. Due to possible underreporting in high-intensity phases, actual interception rates may be slightly higher, with an estimated deviation of less than 5 %.

About the Author

Marcus Welsch is a freelance analyst, documentary filmmaker, and publicist.

Since 2014, he has specialized in OSINT journalism and data analysis, focusing on the Russian war against Ukraine, military and foreign policy issues, and the German public discourse.

In cooperation with Kyiv Dialogue, he has conducted research and panel discussions on Western sanctions policy since 2023.

Since 2015, he has been running the data and analysis platform ↗ Perspectus Analytics.

About Kyiv Dialogue

Kyiv Dialogue is an independent civil society platform dedicated to fostering dialogue between Ukraine and Germany.

Founded in 2005 as an international conference format addressing social and political issues, it has moved to support civil society initiatives aimed at strengthening local democracy in Ukraine since 2014.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the focus has shifted to social resilience, cohesion, and security policy—including military support for Ukraine and Western sanctions policy.

Kyiv Dialogue is a program of the European Exchange gGmbH.

CONTACT

Kyiv Dialogue

c/o Europäischer Austausch gGmbH Erkelenzdamm 59, D-10999 Berlin +49 30 616 71 464-0 info@kyiv-dialogue.org www.kyiv-dialogue.org

Konrad Adenauer Foundation Ukraine

Bogomoltsja St. 5, Wh. 1, 01024 Kyiv / Ukraine

+38 044 4927443 office.kyiv@kas.de

www.kas.de/de/web/ukraine

You need to sign in in order to comment.