Summary

- In January, the Russian Air Force attacked Ukrainian cities and civilian targets with 4,442 long-range drones – 13% less than in the previous month and the lowest figure since August 2025. In addition, there were 76 ballistic missiles (31% more than in December) and 61 cruise missiles (50% less than in December).

- Russian missiles caused more targeted and extensive damage, despite slightly improved interception rates for drones (83%) and ballistic missiles (40%).

- A total of 820 missiles and drones penetrated air defenses (750 drones) in January, compared to 1,052 in December (987 drones).

- Russia deployed a Geran-5 drone for the first time and, for the second time in this war, an Oreshnik medium-range missile, which, however, served primarily a propaganda function.

- In January, the situation for the civilian population worsened significantly. Three years of aerial warfare – with 612 targeted attacks on energy infrastructure – have severely destabilised the Ukrainian power grid.

- On 31 January, cascading failures, including the throttling of nuclear power plants, led to a widespread power outage. With temperatures below −15 °C, this resulted in the most severe power, water, and heating failures since the start of the war; More than one million households were affected in Kyiv alone.

- Civilian casualties of the air war have risen sharply, by more than 30% over the past year. According to estimates, 15,000 civilians have been killed since February 2022, including nearly 800 children. In some places, the targeted hunting of people is now part of the training of Russian drone pilots.

- The Russian army is using Starlink components to increase the range of its drones. This sparked international protests at the end of January. Starlink operator SpaceX subsequently gave assurances that it would restrict the military use of the satellite network by the Russian armed forces.

- A Norwegian study (NUPI/Corisk) compares two options for European policy on Ukraine against the backdrop of dwindling US security guarantees for Europe and the risk of parallel major conflicts in Europe and Asia. Insufficient support for Ukraine could lead to a Russian (partial) victory with estimated additional costs of 1.2–1.6 trillion euros due to the consequences of migration and instability, as well as enormous European defence spending, primarily for deterrence in northern Scandinavia and the Baltic states. Significantly stronger military support for Ukraine is considered to be more effective in terms of security policy and significantly more cost-effective in the long term.

Situation in January 2026. Analysis and trends

Despite improved interception rates, Russian missiles are now causing more targeted and extensive damage than before, with lasting consequences for the population's electricity and heat supply. Timely repairs are hampered by short attack intervals. (↗ Armyinform, 20.1.2026). In January, the Russian Air Force attacked Ukrainian cities and civilian targets with significantly fewer missiles than in previous months. A total of 4,442 long-range drones were counted – the lowest number since August 2025. This is 13% less than in December 2025, and an average of 143 drones per night.

Ukrainian drone defence achieved a slightly better interception rate of 83% in January (December: 81%). A total of 820 missiles and drones penetrated air defenses (750 drones), compared to 1,052 in December (987 drones).

Russia deployed a Geran-5 drone for the first time in January. It has a range of approximately 1,000 km and can be equipped with an air-to-air missile (R-73) (↗ HUR, 11.1.2026).

The number of cruise missiles deployed by Russia halved to 61 compared to the previous month, with the interception rate varying depending on the type (62% on average). The number of ballistic missiles increased again to around 76 (December: 57).

In addition to the Iskander-M missiles, Russia also deployed modified training missiles from the S-300/S-400 air defence missile series. These surface-to-air missiles have been used in the past to attack ground targets in Ukraine. The fact that training ammunition was used suggests shortages of these air defence missiles, which are important to Russia and were still available in large numbers before 2022. Presumably, the ongoing Ukrainian attacks are forcing Russia to prioritise the use of its air defence ammunition (↗ ISW, 201.2026). Unlike in previous months, the Ukrainian Air Force (KPSZSU) did not report any attacks with Kinzhal missiles in January.

Missiles deployed by Russia per month

The interception rate for ballistic missiles rose to nearly 40% in January. This is the best figure since August 2025 and may be related to an unspecified delivery of US PAC-3 interceptor missiles for the Patriot air defence systems (↗ Presidential Administration of Ukraine, 23.1.2026).

On the night of 9 January, Russia used a modified Oreshnik medium-range missile for the second time in this war in attacks on Lviv. Similar to its first use in November 2024 (↗ Monitor Vol. II), the missile did not carry a warhead. The relatively expensive Oreshnik missiles are designed to be equipped with nuclear warheads, which are less dependent on precision than conventional attack weapons and serve primarily propaganda purposes rather than military impact (↗ ZDF, 16.1.2026).

FATAL ATTACKS ON THE ENERGY SUPPLY

Since autumn 2022, Russia has attempted to disrupt Ukraine's energy supply every winter (↗ see Monitor Vol. XII), but without significant success for a long time (↗ Monitor Vol. III). Since autumn 2025, the situation has worsened dramatically as the Russian army has focused its attacks even more specifically and intensively on energy infrastructure, causing lasting damage to the power grid. The attacks have become more frequent, and repair teams have been targeted.

The consequences of the attacks in December and January affected the civilian population to an unprecedented extent and, with temperatures below −15 °C, led to the most severe power, water, and heating outages since the start of the air war.

At times, more than one million households in Kyiv and hundreds of thousands more in Chernihiv, Odesa, and other areas were without power; due to regional rolling blackouts, people often had only three to four hours of electricity in their homes per day.

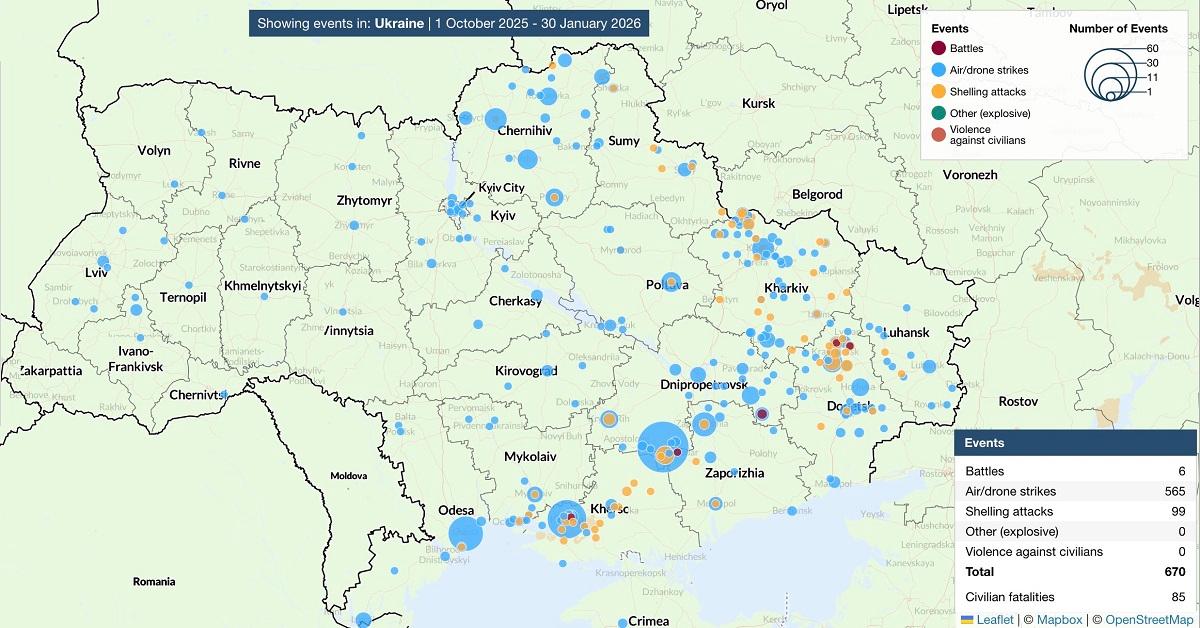

Attacks in January 2026 were concentrated in a few Ukrainian regions (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, Zaporizhzhia).

Perspectus Analytics, KPSZSU, ISW daily reports

Ukraine's largest private energy company, DTEK, has now lost 60–70% of its electricity generation capacity. The damage to the energy sector is estimated at 64–70 billion US dollars (↗ Reuters, 23.1.2026). According to Ukrainian Energy Minister Denys Shmyhal, Russia has attacked every single power plant in Ukraine since 2022, with a total of 612 attacks on energy infrastructure recorded. To stabilise supply, 250 cogeneration plants have been put into operation and 200 more are under construction; more than 15,000 employees are helping with repairs (↗ Suspilne, 16.1.2026).

WIDESPREAD POWER OUTAGES AND EMERGENCY SHUTDOWNS

Months of Russian attacks have weakened the Ukrainian power grid to such an extent that even a moratorium on attacks on energy infrastructure cannot stabilise the situation in the short term.

This became particularly clear during a power outage on 31 January, which was not caused by Russian attacks that night, but by the failure of two lines to the power grids in Moldova and Romania and between western and central Ukraine (↗ Shmyhal, 31.1.2026).

Existing damage to the energy system led to cascading shutdowns across the entire grid. Ukrainian nuclear power plants also had to be throttled again (↗ Kyiv Independent, 31.1.2026). The additional loss of this capacity was particularly serious, as nuclear power plants play a key role in stabilising the supply.

This resulted in emergency shutdowns in several regions. In Kyiv, metro operations were abruptly interrupted, leaving trains and passengers stuck in tunnels. Until then, the metro in the capital had been secured by a separate power supply.

Power to critical infrastructure and most railway lines was restored during the course of the day, but the supply to the population remained uncertain. At times, the water supply and parts of the battery-backed emergency power supply for the mobile phone network also failed.

Overall, the Ukrainian power grid is now so badly damaged that even minor disruptions can have a significant impact. The country's power supply now depends primarily on its three nuclear power plants. The remaining thermal power plants are mainly used for heat generation. The electricity supply for the Odesa Oblast is considered particularly critical. The region has been struggling with permanent power shortages for two months (↗ see Monitor Vol. XII).

The "moratorium" on attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure announced by Trump on 29 January is not a substantial concession by Russia. There have been repeated ceasefires lasting several days since the start of the air war. These have always served as preparation for Russia's next attacks. The end of the "moratorium" culminated in the most massive missile attack of the winter on 3 February, with 71 ballistic missiles deployed (↗ Kyiv Independent, 4.2.2026).

RUSSIA'S STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES IN THE WAR AGAINST ENERGY SUPPLIES

According to military analyst Konrad Muzyka, since the summer of 2025, Russian attacks have primarily targeted smaller substations and energy network hubs near the Russian border for strategic reasons. This forced Ukraine to withdraw its repair teams and air defence capabilities from important targets in the hinterland (↗ Rochan Consulting, 26.1.2026).

Previously, gas and coal-fired power plants had been the focus of attacks. Strategically important coal mines were destroyed and shut down before 2025. Hydroelectric and combined heat and power plants were also systematically attacked (↗ Texty.org, 6.11.2025).

In 2026, gas supplies could become a crucial challenge for Ukraine. By October 2025, 60% of Ukraine's natural gas production had already been destroyed (↗ see Monitor Vol. X). The attack on a gas compressor station in Orlivka (Odesa Oblast) in August 2025 shows that Russia is also targeting import and storage logistics (↗ OSW, 12.8.2025).

Furthermore, the attacks on Ukrainian railway infrastructure should be understood as part of the Russian armed forces' ongoing Battlefield Air Interdiction (BAI) air strikes aimed at disrupting Ukrainian defence logistics. This is increasingly affecting civilian structures such as motorways and rail transport (↗ see Monitor Vol. XII).

15,000 CIVILIAN DEATHS

Civilian casualties of the air war against Ukraine have risen sharply, by more than 30% over the past year. In 2025, Russian attacks killed around 2,400 Ukrainian civilians and injured almost 12,000. The total number of civilian deaths since February 2022 is estimated at 15,000, with an additional 40,000 injured – including 758 children killed and 2,445 injured (↗ Bloomberg, 12.1.2026).

63% of all civilian casualties in 2025 were killed in frontline areas. A disproportionate number of these were elderly people, most of whom died in targeted attacks by Russian short-range drones. Such attacks increased by 120% over the past year (↗ HRMMU, 12.1.2026), which is partly due to the significantly increased range of FPV drones.

TARGETED DRONE HUNTING OF PEOPLE

The Russian army is not only systematically attacking hospitals and medical facilities in Ukraine, but also hunting down civilians with FPV drones, which allow the pilot to see the drone's camera image in real time. (↗ DW, 27.1.2024).

The Russian army apparently uses FPV drones to train drone pilots, allowing them to hunt people for training purposes in order to prepare them for deployment on the front line. This includes attacks on private cars, supply vehicles and even rubbish collection trucks, as reported from the Kharkiv region (↗ Armyinform, 24.1.2026).

Geolocated footage shows how Russian FPV drones hunted down and killed civilians in Hrabowske, southeast of the city of Sumy, at the end of January as they attempted to leave the occupied territory. At the same location, drone pilots attacked a wounded man lying next to a woman who had been killed by a drone. In December, the Russian army forcibly displaced about 50 civilians in a series of attacks in the region (↗ ISW, 27.1.2026).

RUSSIAN ILLEGAL USE OF STARLINK

Experiments by American research institutions have long proven that Starlink signals can also be used indirectly for complex navigation and are being used in conflict regions. The Ukrainian army uses the Starlink satellite network operated by the US space company SpaceX on many levels. Numerous applications that give Ukraine a technical advantage are based on this infrastructure, which will also play an increasingly important role in the navigation of deep strikes in Russia (↗ Benjamin Cook, 14.1.2026).

Russia's use of the Starlink signal was already discussed in February 2024 (↗ LB.ua, 11.2.2024). In September 2024, there were reports of Russian Shahed long-range drones equipped with Starlink antennas (↗ Reuters, 29.1.2026).

In December 2025, the Ukrainian military intelligence service HUR stated that the modified Russian Molniya-2 drone was also equipped with Starlink components (↗ HUR, 22.12.2025), which can extend its range from 30 to up to 230 kilometres (↗ Unian, 29.12.2025). Other models are said to be controllable from up to 500 kilometres away (↗ Beskrestnov, 26.1.2026). This poses new challenges for the Ukrainian army in protecting its supply routes.

Civilian vehicles have also been attacked by drones equipped with Starlink receivers (↗ Suspilne, 29.1.2026). At the end of January, a passenger train in the Kharkiv region was presumably hit by a modified Shahed long-range drone, leading to an exchange of blows between Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski and Starlink owner Elon Musk (↗ CBS News, 28.1.2026).

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence announced that it would work with Starlink operator SpaceX to introduce a verification mechanism to prevent the Russian army from using Starlink (↗ EuroNews, 2.2.2026).

SPOTLIGHT. The price of Europe's inadequate aid to Ukraine

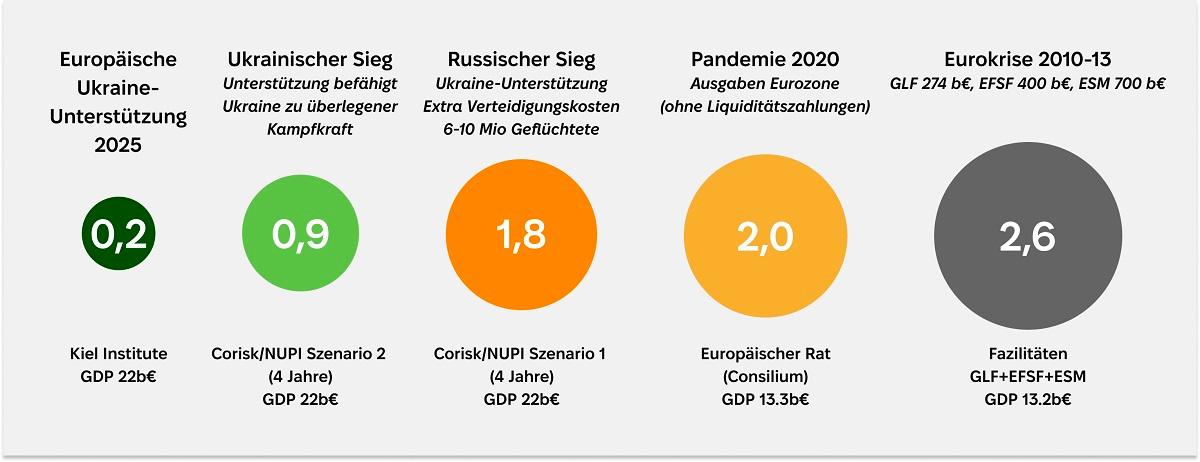

A Russian victory in Ukraine would jeopardise Europe's security – and incur high costs. This is the conclusion of a study published in November by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and the independent analysis firm Corisk, which compares two alternative paths for European policy on Ukraine (↗ NUPI/Corisk, 11.2025) and analyses their security policy consequences and costs.

According to the study, a (partial) success in Ukraine would not only strengthen Russia militarily, but also encourage it to expand its power claims in Europe, while the US would be limited in its ability or willingness to continue to guarantee Europe's security, especially in the event of a hot conflict with China in the Indo-Pacific. Europe is already no longer the focus of the new US defence strategy (↗ DLF, 24.1.2026).

The NUPI report points out that Russia and China have a common interest in tying down the US militarily and weakening its global influence: it is likely that major wars will take place simultaneously in Asia and Europe – between China and the US, and between Russia and Europe.

Europe must therefore be prepared to sustain war against Russia even without extensive support from the US. A possible conflict between the US and China would shift (air) defence capabilities to protect US soldiers in the Pacific region and reduce support for Europe. It is hardly realistic to expect US ground and air forces to be deployed in Europe on a significant scale without their logistics routes and bases being adequately protected.

Due to the low global production capacity for highly effective air defence systems and missiles, Europe already has only limited ability to protect itself against ballistic missiles from Russia (↗ see Monitor Vol. VIII).

Defending Scandinavia and the Baltic states is key to deterring and countering Russian power grabs. This is particularly true in view of a possible Russian advance into northern Finland and northern Scandinavia, where Russia could attempt to expand the buffer zone around the Kola Peninsula – a core area of its nuclear deterrence – by attacking NATO territory.

After Russia has already threatened Finland with rhetoric similar to that previously used against Ukraine (↗ see Monitor Vol. VIII), the latest satellite images for the period from June 2024 to October 2025 show extensive Russian construction activity at the Rybka military base near Petrozavodsk (Republic of Karelia) and the construction of a new military base in Kandalaksha (Murmansk Oblast) near the Finnish border. Accordingly, Russia is reactivating abandoned sites, stationing new units, and thus creating the military conditions for a long-term orientation toward a possible confrontation with NATO in Scandinavia (↗ ISW, 1.2.2026).

Against this global political backdrop, the report develops two scenarios:

SCENARIO 1: INSUFFICIENT MILITARY SUPPORT FOR UKRAINE AND RUSSIAN (PARTIAL) VICTORY

If military support for Ukraine is not significantly increased, the authors of the study believe there is a risk of a Russian (partial) victory: Ukraine could lose around half of its territory, remain politically and economically unstable, and be dependent on extensive aid from Europe in the long term.

The study estimates that the resulting refugee and social costs for Europe alone would amount to between 524 billion and 952 billion euros over the next four years. In addition, there would be massive additional defence spending to prevent further Russian attacks, particularly in the Baltic states and Northern Europe.

Overall, the costs of this scenario would amount to 1.2 to 1.6 trillion euros in the first four years. Europe would also have to station significantly more troops in Northern and Eastern Europe than is currently assumed in public debates.

SCENARIO 2: DECISIVE MILITARY SUPPORT FOR UKRAINE

Substantially stronger support for the Ukrainian army would enable smaller military successes that could force Russia to engage in serious negotiations in the first place. This would give Ukraine realistic prospects for the future, including the possibility for many Ukrainians to return to their country.

To achieve this, European countries would have to provide more drones, but above all significantly more tanks and artillery systems. In addition, improved air defence should provide Ukraine with noticeable relief (↗ see Monitor Vol. IX). The authors estimate the cost of this at between 522 billion and 838 billion euros over the next four years. This is less than the EU's expenditure on tackling the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 or on the euro rescue package in 2010–2013.

The study's unequivocal conclusion is that it is not greater support for Ukraine that is the expensive option, but its failure. Looking at both scenarios as a whole, it is clear that Europe can no longer afford strategic ambiguity and must finally formulate and resolutely implement a coherent strategy that combines political goals, military support, long-term security interests, and financial costs.

Method

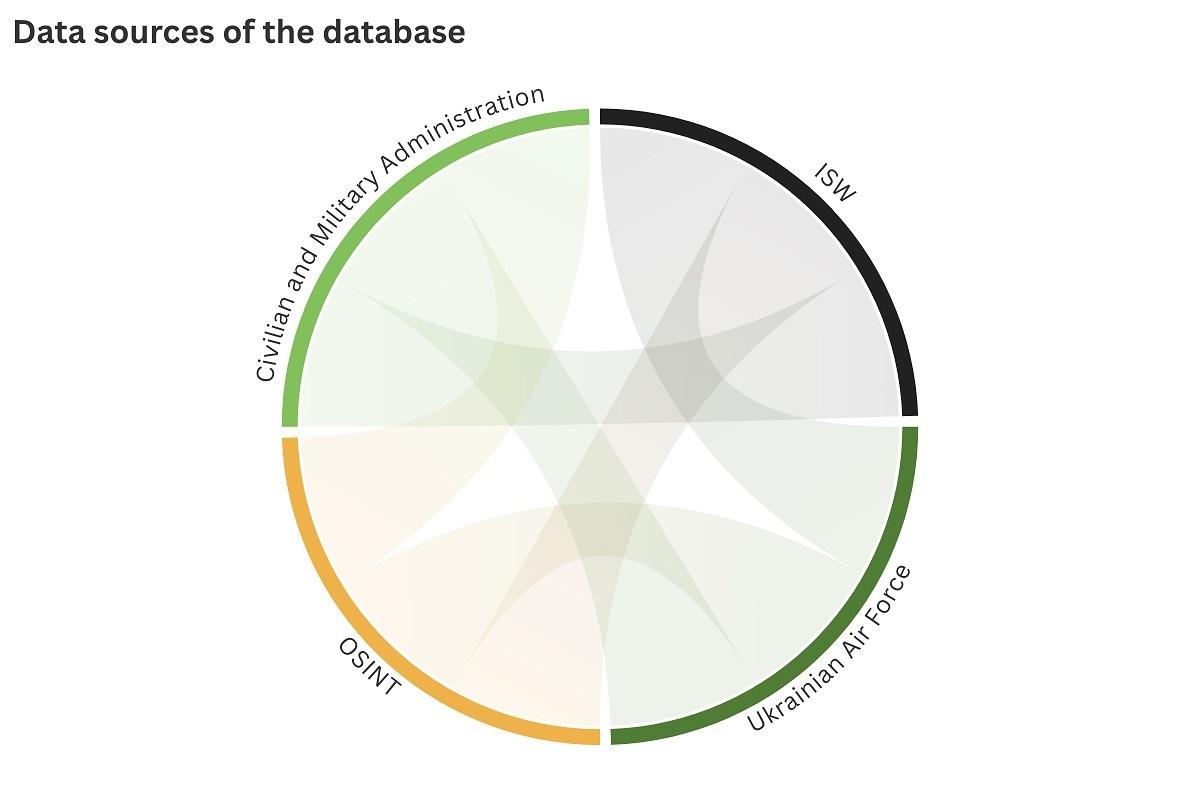

The air strike database is regularly cross-referenced with daily reports from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) in Washington (↗ ISW).

The launch records originate from the Ukrainian Air Force reports (↗ KPSZSU), and data on regional targets and damage—if available—is supplemented with civilian and military administration sources.

These figures are further verified using additional OSINT sources and are considered highly reliable.

Accurately quantifying air strike damage during an active war is inherently challenging. Providing overly precise information could aid Russian military planning, which is why certain reporting restrictions apply (↗ Expro, 2.1.2025).

Consequently, this analysis focuses on attack patterns and dynamics rather than detailed damage assessments.

With over 41 months of data and around 79,700 documented attacks, robust trends have emerged. Monthly missile counts are approximate values, as irregularities have been noted in Ukraine’s reporting system. Discrepancies with other OSINT sources remain within a 10% margin, often below 3%.

A comparison with the missile and drone assessment by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington over a period of more than two years shows a deviation of only 1.6% (↗ CSIS).

For attacks lacking definitive quantification, the lowest plausible estimates have been used. Due to possible underreporting in high-intensity phases, actual interception rates may be slightly higher, with an estimated deviation of less than 5%.

About Us

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marcus Welsch is a freelance analyst, documentary filmmaker, and publicist.

Since 2014, he has specialized in OSINT journalism and data analysis, focusing on the Russian war against Ukraine, military and foreign policy issues, and the German public discourse.

In cooperation with Kyiv Dialogue, he has conducted research and panel discussions on Western sanctions policy since 2023.

Since 2015, he has been running the data and analysis platform ↗ Perspectus Analytics.

ABOUT KYIV DIALOGUE

Kyiv Dialogue is an independent civil society platform dedicated to fostering dialogue between Ukraine and Germany.

Founded in 2005 as an international conference format addressing social and political issues, it has moved to support civil society initiatives aimed at strengthening local democracy in Ukraine since 2014.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the focus has shifted to social resilience, cohesion, and security policy—including military support for Ukraine and Western sanctions policy.

Kyiv Dialogue is a program of the ↗ European Exchange gGmbH.

CONTACT

Kyiv Dialogue

c/o Europäischer Austausch gGmbH Erkelenzdamm 59, D-10999 Berlin +49 30 616 71 464-0 info@kyiv-dialogue.org www.kyiv-dialogue.org

Konrad Adenauer Foundation Ukraine

Bogomoltsja St. 5, Wh. 1, 01024 Kyiv / Ukraine

+38 044 4927443 office.kyiv@kas.de

www.kas.de/de/web/ukraine

You need to sign in in order to comment.