Issue: 1/2025

The South China Sea has long been a geopolitical flash point, but the situation has grown even more volatile in recent months. Clashes have become more frequent and dangerous, especially between Chinese and Philippine vessels. Chinese ships have repeatedly forced Philippine boats off course, resulting in serious collisions and confrontations, while in some cases, Chinese forces have used water cannons and lasers against Philippine crews and fishermen. The risk of further escalation looms large.

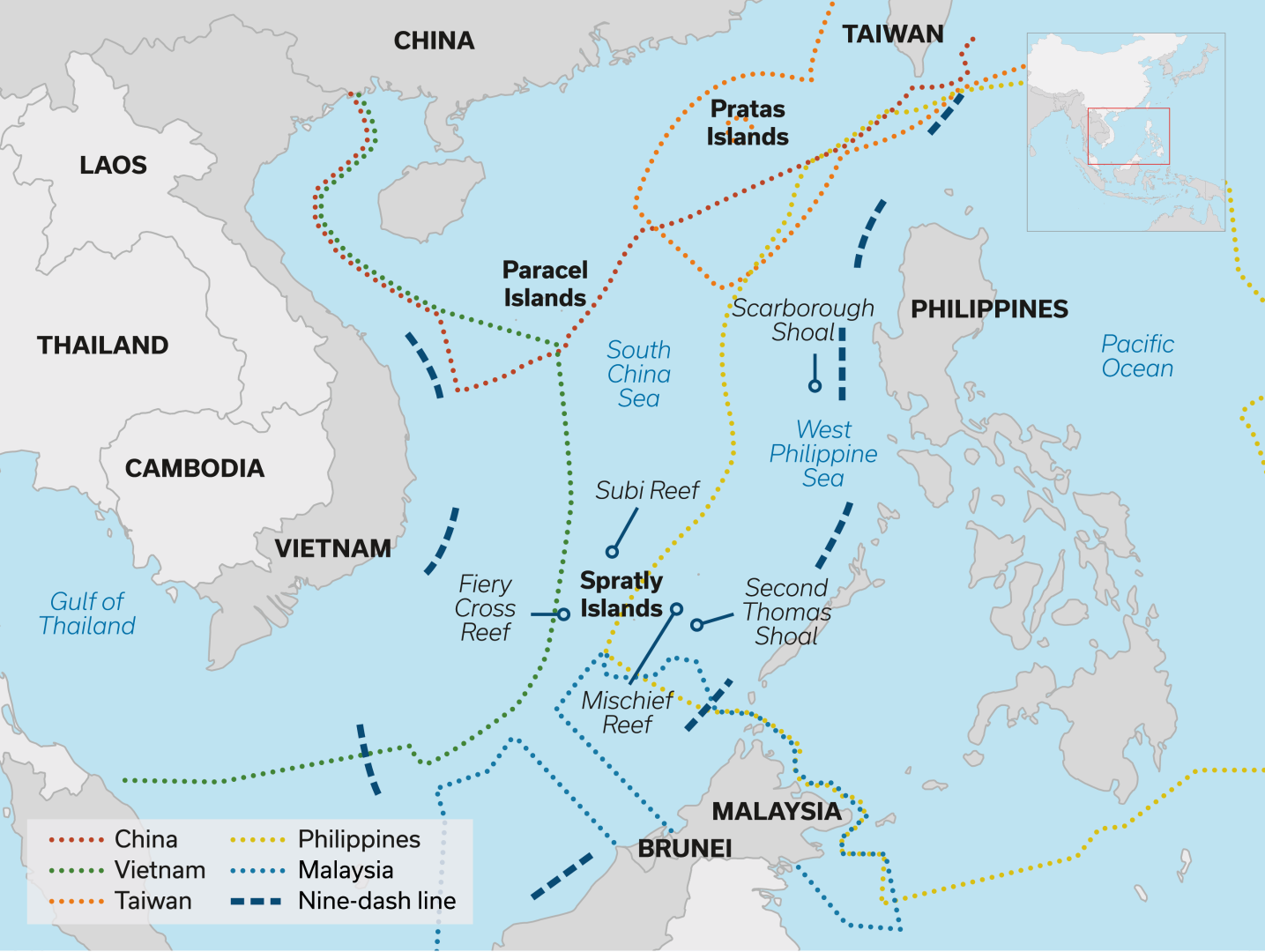

Multiple nations have faced off for decades over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea. This long-standing dispute has led to military confrontations between China and Vietnam on two occasions: first in 1974, and then again in 1988. Since the 1970s, the South China Sea’s coastal nations – China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei – have laid claim to various islands, reefs, atolls and maritime zones. The result is a tangled web of overlapping territorial assertions, particularly around the four major island groups: namely the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Pratas Islands and Scarborough Shoal. With the exception of Brunei, every claimant has built structures on reefs or atolls, many of which have been expanded for military use.

The South China Sea is a vital lifeline for most of the surrounding countries. It is rich in fish stocks, thereby making it crucial for food security and trade in the region, while large reserves of oil and natural gas are believed to lie beneath its seabed. Beyond its role in regional stability, the South China Sea is of global importance. As a key maritime trade route, developments in these waters can have far-reaching economic consequences worldwide. As a key security ally to Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and Taiwan, the United States has repeatedly emphasised to Beijing that it takes its defence commitments seriously. For China, the conflict is about more than resources – it is a matter of military strategy and securing control over Pacific trade routes, with undisputed dominance in the South China Sea playing a critical role in the country’s broader geopolitical ambitions.

China’s Aggressive Approach

Citing historical justifications and basing its assertions on the “ten-dash line” (formerly the “nine-dash line”), the People’s Republic of China claims more than 90 per cent of the South China Sea for itself. For years, Beijing has pursued the rapid expansion of artificial islands and military outposts with unprecedented speed and determination. Time and again, China’s maritime militia, coast guard and navy have pushed deep into the waters of neighbouring states, harassing fishermen and coast guard vessels while maintaining control over key areas. This aggressive approach is known as grey-zone tactics, which are coercive actions that fall short of outright war yet still challenge the sovereignty of other nations. Coastal states must constantly contend with Chinese incursions into their exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which extend up to 200 nautical miles (370.4 kilometres) from their shorelines. These violations not only undermine national sovereignty, but also inflict serious economic damage since China frequently disrupts traditional fishing grounds, thereby resulting in significant losses for local industries.

Fig. 1: Exclusive Economic Zones and Territorial Claims in the South China Sea

Legally, the situation is clear: Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), China repeatedly violates the sovereignty of its neighbouring states. In a landmark 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, the tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines, rejecting China’s historical claims. However, to this day, Beijing refuses to recognise the decision.

Given China’s aggressive and unlawful conduct, the key question remains: How can smaller nations stand up to such an overwhelming opponent? What strategies are countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam employing to defend their sovereignty against the world’s most powerful naval force, and how effective are they?

Philippines and China on a Collision Course – The Role of the US as a Security Ally

Clashes between Philippine and Chinese vessels were almost a weekly occurrence in 2024, but the incident on 17 June was by far the most violent. The Philippine military was en route to a routine resupply mission at Second Thomas Shoal – a shallow coral reef about 200 kilometres west of Palawan that is best known as the site of the deliberately grounded BRP Sierra Madre, a rusting Philippine naval ship that serves as a strategic outpost. Before reaching their destination, however, they were aggressively intercepted by the Chinese coast guard. Footage of the confrontation shows Chinese forces ramming Philippine boats, hacking at equipment with pickaxes and knives and physically attacking the Philippine crew. By the end of the skirmish, one Philippine soldier had been seriously injured. What makes this incident particularly explosive is Manila’s recent warning: As a US treaty ally, the death of a Filipino caused by Chinese actions would be considered a red line – one that could trigger the US-Philippines Mutual Defence Treaty.

A former colonial power, the US is the Philippines’ most important ally. Several defence agreements are in place, and under the 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty, the US would come to Manila’s aid in the event of war. Since President Marcos took office on 30 June 2022, relations have deepened further, not least in response to China’s aggression in the South China Sea. This is particularly evident in the recent announcement that the US will gain access to four additional military bases in the Philippines. This brings the total to nine Philippine bases where US troops can be deployed on a rotational basis. An escalation between the Philippines and China in the South China Sea would therefore also involve the US, which has repeatedly emphasised in recent years – including during the first Trump presidency – its commitment to defending its oldest treaty partner in the region.

Gradual Chinese Occupation in Philippine Waters

The territorial dispute between the Philippines and China can be traced back to the gradual Chinese occupation of Mischief Reef in the mid-1990s. A traditionally important Philippine fishing ground just 130 nautical miles west of Palawan, this reef forms part of the Spratly Islands. Having been artificially expanded by means of land reclamation, Mischief Reef now hosts a Chinese airbase. As a result, Manila has lost access to the reef within its own EEZ and instead faces a military outpost of a hostile power right on its doorstep.

Another pivotal incident in the South China Sea occurred in 2012 at Scarborough Shoal. After the Philippine navy discovered Chinese fishermen illegally harvesting coral at the atoll, a dangerous two-month standoff ensued between Manila and Beijing. The crisis was eventually defused through US mediation, with both sides agreeing to withdraw their vessels. However, while the Philippines complied, China ignored the deal and remained at Scarborough Shoal – without consequences. This incident ultimately led the Philippines to take its case to the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Marcos Administration Takes a Firm Stance against China

While close ties with the United States have been a cornerstone of Philippine foreign and security policy since the country’s independence, different administrations have taken varying approaches to dealing with China, thereby influencing Manila’s actions in the South China Sea. Following a serious incident involving the Chinese at Second Thomas Shoal in February 2023, the current Marcos administration decided to pursue a significantly different course to that of its China-friendly predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte. The government is now employing a range of measures to defend the country’s sovereignty and prevent further territorial losses to China in the West Philippine Sea, which is the official name for the part of the South China Sea within the Philippine EEZ.

These measures include the so-called transparency initiative, the strengthening of alliances and partnerships, the strategic use of international law, the modernisation of the coast guard and military and the reinforcement of outposts in the West Philippine Sea, particularly of the deliberately grounded Philippine vessel BRP Sierra Madre at Second Thomas Shoal. Although the current administration is taking a much firmer stance against Beijing’s aggression in the South China Sea, it remains committed to keeping diplomatic channels with China open and to seeking peaceful solutions.

Using Transparency against a Dominant Opponent

A central element of the current government’s approach is the transparency initiative, which aims to expose China’s grey-zone tactics in Philippine waters to both the public and the international community while revealing the hypocrisy of Beijing’s self-proclaimed image as a major international power that acts peacefully and responsibly. This initiative is not a formally defined strategy, and statements regarding it can vary depending on whom one asks within the Philippine government.

With regard to its goals and effectiveness, Commodore Jay Tarriela – Head of the West Philippine Sea Transparency Office – acknowledges that it is not a miracle solution that will immediately alter China’s actions; rather, he says, the objective is to rally support among both the Philippine public and the international community for the stance adopted by the Philippines. In this respect, the transparency initiative appears highly effective because diplomatic backing for Manila’s position in the South China Sea has gained significantly in strength. Each time a confrontation occurs between Philippine and Chinese vessels, a wave of solidarity follows, with statements of support from the US, Australia, Japan, the EU and numerous European countries, including Germany. And this is not just rhetoric: Indeed, the list of security and defence agreements and partnerships announced or finalised in recent months is extensive and includes countries such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, Singapore, Vietnam, Germany, the United Kingdom and France. The transparency initiative has played a key role in fostering and strengthening relationships, particularly with middle powers in the region as well as with the EU. With growing international support, Manila’s position has grown stronger.

It remains unclear whether the transparency initiative has had any deterring effect or led to a change in Beijing’s behaviour, however. Data from the US think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) indicates that China has deployed more vessels in Philippine waters and that the frequency and intensity of confrontations have escalated. The type of ships, or actors, that China is deploying also indicates that Beijing is continuing to focus on escalation and intimidation: In December 2024, it was reported for the first time that People’s Liberation Army Navy vessels had approached Philippine boats, shadowed them and conducted aggressive manoeuvres.

Nevertheless, it is unlikely to suit China’s calculations for a “small nation” to publicly defy Beijing and repeatedly show the world the illegal means to which China is willing to resort. What is more, there were numerous clashes between the two countries even under markedly China-friendly President Duterte, though reporting on these clashes was not permitted.

The current Philippine approach can be seen as a bold response by a smaller nation with limited resources to the unlawful and aggressive behaviour of an overwhelmingly powerful opponent. It is up to Beijing to change its actions and render the transparency initiative unnecessary rather than for Manila to turn a blind eye to this behaviour.

China’s Aggressive Tactics towards Vietnam

While international attention is primarily focused on China’s actions in the Philippine EEZ and the high-profile confrontation between Beijing and the US ally Manila, tensions are hardly less fraught hundreds of nautical miles to the west. Vietnamese fishermen are also regularly harassed by Chinese vessels. At the same time, China repeatedly conducts underwater survey operations, often in close proximity to Vietnam’s offshore oil and gas reserves. There are also reports citing US intelligence sources that suggest that China is responsible for acts of sabotage against Vietnam’s undersea fibre optic cables in the South China Sea. China’s grey-zone intimidation tactics are just as common in the so-called East Sea – Vietnam’s name for the South China Sea.

Vietnam’s Approach to Securing Its Maritime Sovereignty

Due to its one-party communist system, geostrategic position, historical experience and non-aligned status, however, Vietnam takes a different approach to China’s actions from that of the Philippines. The Philippine transparency initiative is sometimes referred to in Vietnam as “megaphone diplomacy”. By contrast, Vietnam asserts its sovereignty quietly but firmly. Rather than relying solely on the effectiveness of maritime law or on the endless negotiations over a binding code of conduct, Vietnam pursues a dual strategy of reinforcing its claims through facts on the ground while simultaneously strengthening security cooperation with third countries, including the Philippines.

Another key component is the anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategy, which involves the construction and modernisation of military bases on islands and reefs under Hanoi’s control. It is in this context that Vietnam’s land reclamation efforts in the Spratly Islands must be seen. According to satellite image analysis by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) run by the think tank CSIS, Vietnam has made massive efforts to create new land areas in disputed parts of the South China Sea through dredging and infill – at the expense of fragile underwater ecosystems. Since June 2024 alone, Vietnam has reclaimed some 260 hectares of new land on the Spratlys adding them to the about 280 hectares reclaimed between November 2023 and mid-2024. As a result, Vietnam has now reclaimed a surface which is about three-quarters the size of the area reclaimed by China when Beijing built its seven military bases between 2013 and 2016.

These military bases have given China a significant strategic advantage. With Mischief Reef, Subi Reef and Fiery Cross, Beijing controls the largest artificial islands in the South China Sea by far, having fully militarised them with anti-ship and air defence missile systems, laser and jamming devices, fighter jets and runways over three kilometres long. This has greatly enhanced China’s ability to monitor, project power over and deter rivals in the disputed waters in addition to having increased the country’s capacity to harass neighbouring states with territorial claims of their own. After all, the artificial islands are not just unsinkable aircraft carriers with palm trees; rather, they also serve as permanent bases with harbours that allow for the continuous deployment of China’s navy, coast guard and maritime militia. These forces frequently clash with the fishing fleets of Vietnam, the Philippines and other regional players.

Vietnam Modernises and Expands Its Military Infrastructure

By adopting a similar approach to China’s land reclamation efforts, Vietnam is positioning itself to modernise and expand its runways and potentially equip its enlarged outposts with advanced weaponry such as anti-ship artillery and guided missiles as well as surveillance capabilities such as radar and defensive structures designed to withstand potential attacks. In the event of a military conflict, this would complicate Beijing’s calculations, thereby serving as a deterrent. At the same time, Vietnam’s outposts – much like China’s own – will likely function as bases for future maritime patrols. This would allow Vietnam to monitor the disputed waters more effectively and to exercise its maritime rights under UNCLOS.

Not a gamechanger on its own, given the militarily asymmetric relationship between Hanoi and Beijing, but still of significant strategic value is the construction of new military airstrips. Previously, Vietnam had only one runway in the archipelago: a 1.3-kilometre airstrip on Spratly Island that is too short for larger transport and surveillance aircraft or bomber operations. However, in the second half of 2024, Vietnam began asphalting a runway twice this length on the artificially created Barque Canada Reef that is long enough to accommodate fighter jets. Satellite images also suggest that another military airstrip may be under construction on the reclaimed Pearson Reef. Hanoi itself has not commented publicly on these expansion plans.

Reaction to Hanoi’s Actions

None of these actions have escaped Beijing’s attention, yet for a notably long time, China refrained from publicly criticising Hanoi’s activities. No measures have been reported that indicate any attempts to disrupt Vietnam’s land reclamation and expansion plans. It was not until early December 2024 that Chinese experts close to the government began voicing sharp criticism of Hanoi’s actions, with some calling for a more resolute response and warning that if left unchecked, Vietnam’s ongoing construction would only continue, thereby further disrupting the existing balance in the region. The result, they said, would be greater instability and increased uncertainty. Others struck an even more alarmist tone, raising concerns that Vietnam might allow the United States or Japan to use its new airstrips. Given Vietnam’s defence doctrine of non-alignment and bloc neutrality, however, this is not a plausible scenario.

While Western governments have not officially commented on Vietnam’s land reclamation and expansion efforts, the latter have been met with approval among Western experts. These efforts are seen as a potential means of restoring the balance of power in the South China Sea, which has been disrupted by Chinese dominance. Alexander L. Vuving – professor at the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii and a former Fellow of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung – believes that Vietnam’s land reclamation efforts offer hope for re-establishing counterweights to China’s hegemonic ambitions. Vietnam expert Bill Hayton of Chatham House shares a similar view but does not believe that Hanoi’s actions are causing Beijing serious concern or security fears.

It remains to be seen to what extent the public criticism initially voiced by the above-mentioned Chinese experts will herald a new approach in Beijing’s policy. However, it is certainly clear that – apart from one official rejection, in February 2025 – China has thus far remained silent and seemingly passive in response to Vietnam’s activities, even as tensions with the Philippines have continued to rise further east in the South China Sea. As a result, correctly interpreting China’s restraint is seen as being highly significant because it could offer insights into Beijing’s broader conflict behaviour and potential implications for its stance towards other actors, such as the Philippines.

China’s Supposed Passivity towards Vietnam

Experts point to five interrelated factors that could explain China’s apparent passivity. Firstly, Beijing may be unwilling to escalate a second conflict with Hanoi while already facing tensions with Manila out of the fear of diplomatic repercussions. Secondly, China may have concluded that its escalation dominance is limited and that military pressure or intimidation would not force Vietnam into submission. On the contrary, Hanoi has demonstrated both determination and a willingness to take risks, as seen in the 2014 oil rig crisis, which ultimately did not end in Beijing’s favour. The third factor is Vietnam’s non-aligned status, which could work to the country’s advantage in this case because China does not necessarily view Hanoi’s actions in the South China Sea as a direct geopolitical challenge.

Closely linked to this is the fact that as communist-led brother states, Vietnam and China have established reliable party-to-party communication channels, which allows them to resolve differences quietly. Finally, overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea are only one aspect of the broader bilateral relationship. Beyond their ideological ties, the two countries are also close economic partners, officially maintaining a “comprehensive strategic partnership” and committing to the development of a “community with a shared future”. As renowned Vietnam expert and emeritus professor Carlyle Thayer sums it up, it is “a complex relationship, but not antagonistic – like [the] one between China and the Philippines. China is trying to get the US out of the Philippines and the US is not in Vietnam in the same way”.

Manila – Hanoi: An Unlikely Friendship?

The Philippines and Vietnam take differing approaches when it comes to defending their maritime sovereignty. Despite these differences and despite Vietnam – like other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – having criticised the Philippines for its supposedly “noisy” approach, the two countries are the most vocal within ASEAN in pushing back against China’s actions. As a result, cooperation between the two nations is growing, with Manila and Hanoi even being referred to as “besties” within ASEAN. One key area of collaboration is coast guard operations, with joint exercises and training planned in order to strengthen coordination. Another area in which the two nations aim to work more closely together is in responding to incidents in the South China Sea, though the specifics of how this will be implemented remain unclear.

It is a positive development that both countries are seeking closer cooperation over maritime security. Unfortunately, there is little hope for a unified ASEAN response to China’s illegal and aggressive actions in the South China Sea because Beijing’s influence over many Southeast Asian states remains too strong. While negotiations on a code of conduct are still being supported in official rhetoric, behind the scenes few believe that an agreement will be reached anytime soon. This makes it all the more welcome that Vietnam and the Philippines are taking the lead and working more closely together in response to the situation in the South China Sea.

What is Next in the South China Sea?

The South China Sea will remain a geopolitical hotspot that demands the attention of the international community. The risk of a clash spiralling out of control cannot be ignored – particularly between China and the Philippines or Vietnam – because the consequences of an armed conflict in the South China Sea would be felt across the globe.

Germany and Europe must take a stand in order to also defend their interests in this region. The aim here must be to defend the freedom of maritime routes and the rules-based international order while supporting countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam in their fight for sovereignty. In recent years, Germany has already laid important groundwork through its Indo-Pacific guidelines and its increasing engagement in the region. A key signal was given when Germany once again demonstrated its Indo-Pacific commitment with its navy and air force in 2024, this time not shying away from sailing through contested waters. A new German government should further boost Germany’s role in the region, particularly by supporting countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam in their efforts to uphold international law. In this regard, greater importance should be attached to security assistance through military capability-building.

– translated from German –

Daniela Braun is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Philippines Office.

Florian C. Feyerabend is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Vietnam Office.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.