Issue: 2/2025

- Supporters of neocolonial theories argue that the economic challenges facing African states can be explained by continued dependency on Western countries. However, this view overlooks several important realities.

- Over the past decades, the United States and the European Union have granted African states extensive tariff reductions and exemptions even though qualitative product standards can sometimes pose trade barriers. Many African countries themselves maintain high barriers to imports and exports.

- Since gaining independence, African countries have taken starkly differing economic policy paths, and their development has likewise varied, which underscores the importance of internal factors in determining prosperity.

- Africa’s trade is no longer dominated by Europe and the US as it was a few decades ago. Asian countries – first and foremost China – have become major trading partners for many African nations.

- The implementation of the planned African Continental Free Trade Area holds significant potential not only for intra-African trade, but also for cooperation with the EU.

In recent decades, researchers have repeatedly sought to understand why sub-Saharan Africa consistently ranks at the bottom in global assessments of socio-economic progress. While Jeffrey Sachs argues in his book “The End of Poverty” that a “big push” of knowledge and financial support could overcome the lack of progress, for example, Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo takes the opposite view, contending that by absolving governments of responsibility and reducing them to mere recipients, large-scale aid to African countries does more to hinder economic growth on the continent than to help it. Between these two positions are numerous other development economists who point to causes rooted in elites, in state institutions and in social structures. Postcolonial theorists, meanwhile, maintain that “the history of colonialism did not end with formal independence” and that continuing dependencies on former colonial powers – or more broadly, “the West” – continue to obstruct growth and prosperity on the African continent. Particularly common in this context is the claim that the exploitation of Africa’s natural resources is largely to blame for the continent’s lack of economic development. According to this view, neocolonial structures favour Western countries in global trade while exploiting African nations: Africa exports raw materials such as oil and minerals but has to import manufactured goods, thereby creating a trade imbalance that impedes industrialisation and development. Trade barriers are also said to further exclude Africa from meaningful participation in global trade.

African Countries Mainly Export Unprocessed Raw Materials

It is true that African states continue to export primarily unprocessed raw materials, such as crude oil and natural gas, minerals and metals – a pattern that has remained unchanged over the past 30 years. Depending on global market prices, unprocessed raw materials account for between 60 and 89 per cent of Africa’s total export volume, which is also highly unevenly distributed across the continent. From 2016 to 2020, South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, Angola and Morocco exported more than the rest of the continent combined.

It is also true that the export of unprocessed raw materials has numerous disadvantages for countries: The extraction of fuels and the mining of ores and metals are capital-intensive activities but create only a limited number of jobs. Profits are often not reinvested locally and are instead transferred abroad. Only a small group of people benefit, while the domestic industrial sector does not. In addition, commodity prices are volatile and subject to significant exchange rate fluctuations, thereby making countries vulnerable to external shocks and complicating national budget planning.

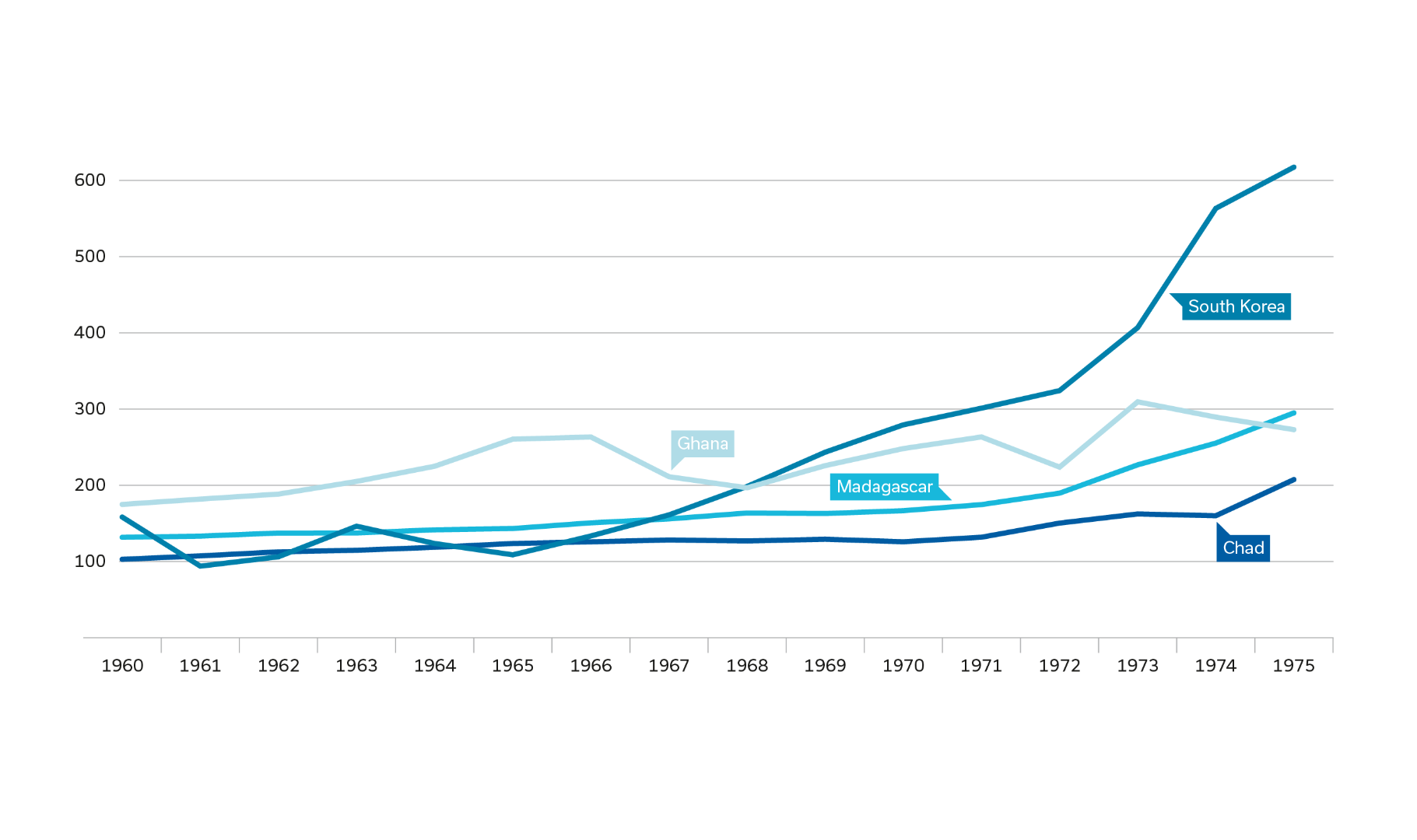

Fig. 1: Per Capita Economic Output in Selected Countries from 1960 to 1975 in US Dollars

While many Asian countries began pursuing systematic diversification of their production and state-supported export strategies as early as in the 1960s, most African countries failed to invest the profits from raw material exports into the development of their industrial sectors. In 1965, for example, per capita income in Ghana, Chad and Madagascar was higher than in South Korea. However, South Korea’s strategic focus on export-oriented production for the global market and on the diversification of its product range played a key role in the country’s subsequent economic rise. At the same time, South Korea was also able to create large numbers of jobs by shifting from low-value to high-value goods. In general, the gross domestic product in Asia grew more than twice as fast as in the industrialised countries from the early 1970s onwards. In contrast to Africa – where growth was largely driven by raw material exports – economic growth in Asia was rooted in structural transformation. This point is also illustrated by the remarkable success of the Chinese economy, which was likewise based on export-led growth.

Various studies have shown that countries with a more diversified production and export structure tend to have higher per capita income and that those producing and exporting more highly processed goods generally experience faster growth. By contrast, Africa has undergone deindustrialisation since the 1970s in two key respects: Firstly, the share of jobs in the manufacturing sector has declined, and secondly, export structures have become less diversified and the produced goods less complex.

Therefore, since gaining independence, many African countries have failed to implement export strategies aimed at diversification and at the development of a domestic manufacturing sector. The fact that African countries primarily export raw materials is a result of these countries’ export models and strategies rather than of neocolonial structures.

Not a Victim of High Trade Barriers

The European Union is Africa’s most important trading partner: Indeed, around 26 per cent of all imported goods come from Europe, followed by China at 15 per cent. These figures are mirrored in Africa’s export destinations, with 26 per cent of exports going to the European Union and 15 per cent to China. For Europe and China, however, trade with Africa is of minor significance, accounting for just 2.2 per cent and 3.9 per cent of their total trade, respectively. These figures clearly illustrate that there is an imbalance in trade relations between Africa and those regions – an imbalance that is unfavourable to Africa. Moreover, although Africa is home to around one-fifth of the global population, it generates only about 4.8 per cent of global GDP, thereby placing the economic output of the entire continent somewhere between that of Japan and India.

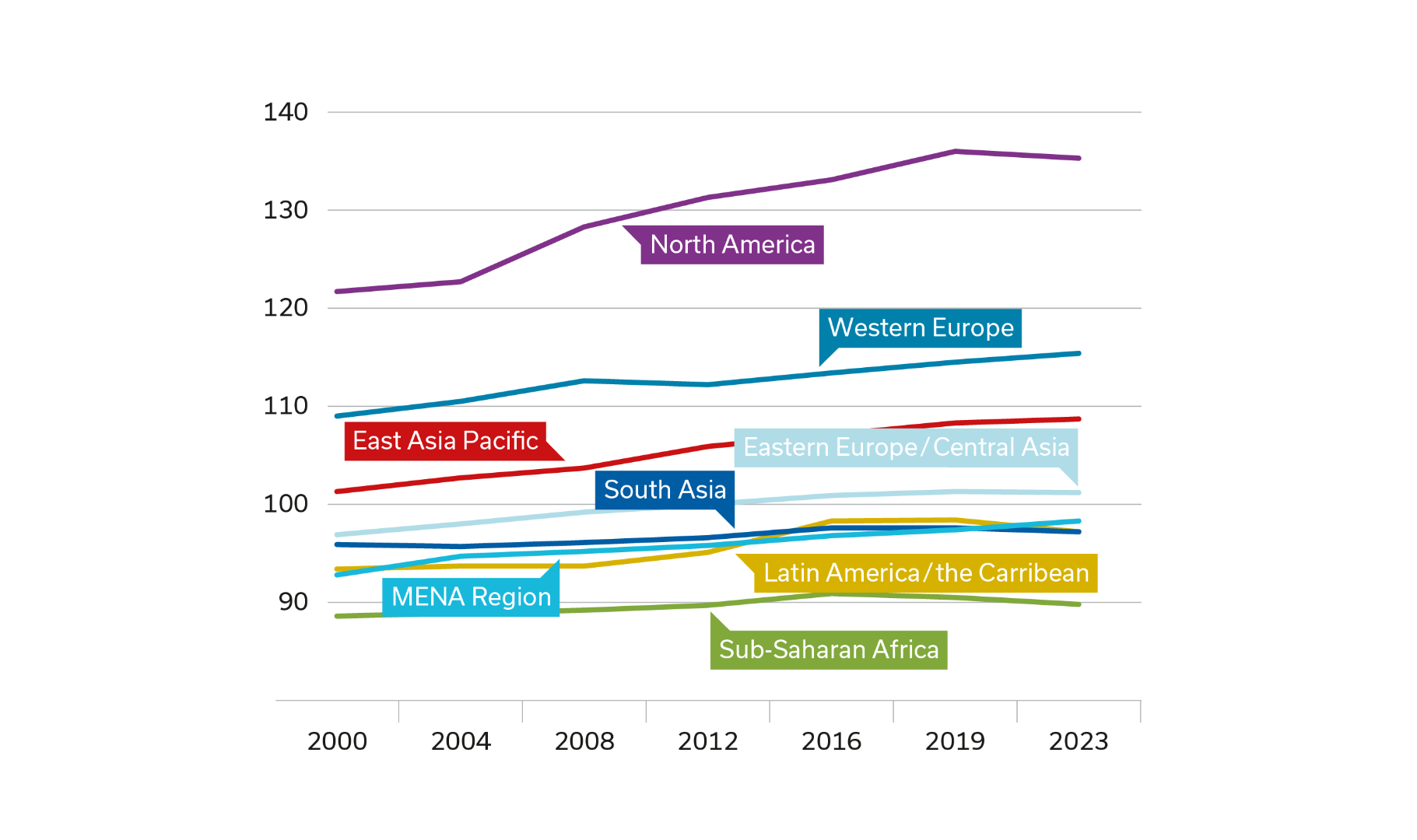

Fig. 2: Economic Diversification by World Region from 2000 to 2023 (EDI Score)

By adopting targeted measures, industrialised countries have sought to improve African businesses’ access to international markets in recent years. Trade agreements between the EU and Africa grant better market access to 19 African countries, while a further 35 countries benefit from the Everything but Arms initiative, which provides duty- and quota-free access to the EU. In 2023, more than 90 per cent of African exports entered the EU tariff-free. This situation ensures that African exporters have transparent and straightforward access. The US government’s African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) – in place since 2000 – allows for the duty- and quota-free import of various products into the United States with the aim of strengthening trade and economic relations between sub-Saharan Africa and the US. Under President Trump, the future of AGOA has become uncertain; but so far, many countries and industries have benefited from its favourable import conditions, including the textile and automotive sectors. Contrary to the widespread assumption that the EU and other industrialised countries shield their markets from Africa through high trade barriers, both the Everything but Arms initiative and AGOA suggest the opposite.

However, strict European quality standards often constitute non-tariff trade barriers, particularly in the agricultural sector. Trade relations under the EU’s Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) also have to be assessed in more nuanced terms. Emerging economies and middle-income countries benefit from improved access to EU markets, but in return, they are also required to open up their own markets. The conditions set out in these agreements are in some cases controversial, with critics arguing that the trade reforms could harm rather than support growth markets in Africa. A final assessment of these structural reforms cannot be made here. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the EPAs also aim to reduce tariffs and quota restrictions, thereby facilitating market access for African goods.

Various statistics – such as the International Trade Barrier Index and the World Bank’s Services Trade Restrictions Index – measure the extent to which a country’s trade policy facilitates or restricts international trade. These indices reveal that African countries themselves maintain significant domestic barriers to imports and exports, both tariff and non-tariff. Non-tariff barriers include lengthy and complex customs procedures, difficulties in obtaining import and export permits and the certification of hygiene standards. Regulations concerning duty drawbacks, customs exemptions and VAT refunds are often opaque, time-consuming and cumbersome, thereby frequently resulting in considerable delays. According to the UN trade organisation UNCTAD, technical requirements, inefficient customs procedures and other import- and export-related issues reduce African trade three times more than the tariffs themselves.

Economic Development of Former African Colonies Is Not Uniform

It is problematic in many respects to claim – as is often the case among proponents of neocolonial theory – that Africa is merely an “object that has fallen victim to foreign subjects”. Indeed, lumping all 54 African states together as a single “Africa” fails to recognise the highly diverse trajectories these countries have followed since gaining independence. Africa expert Nic Cheeseman points out that this trend towards divergence is likely to intensify in the coming years in terms of both economic and democratic development across the continent.

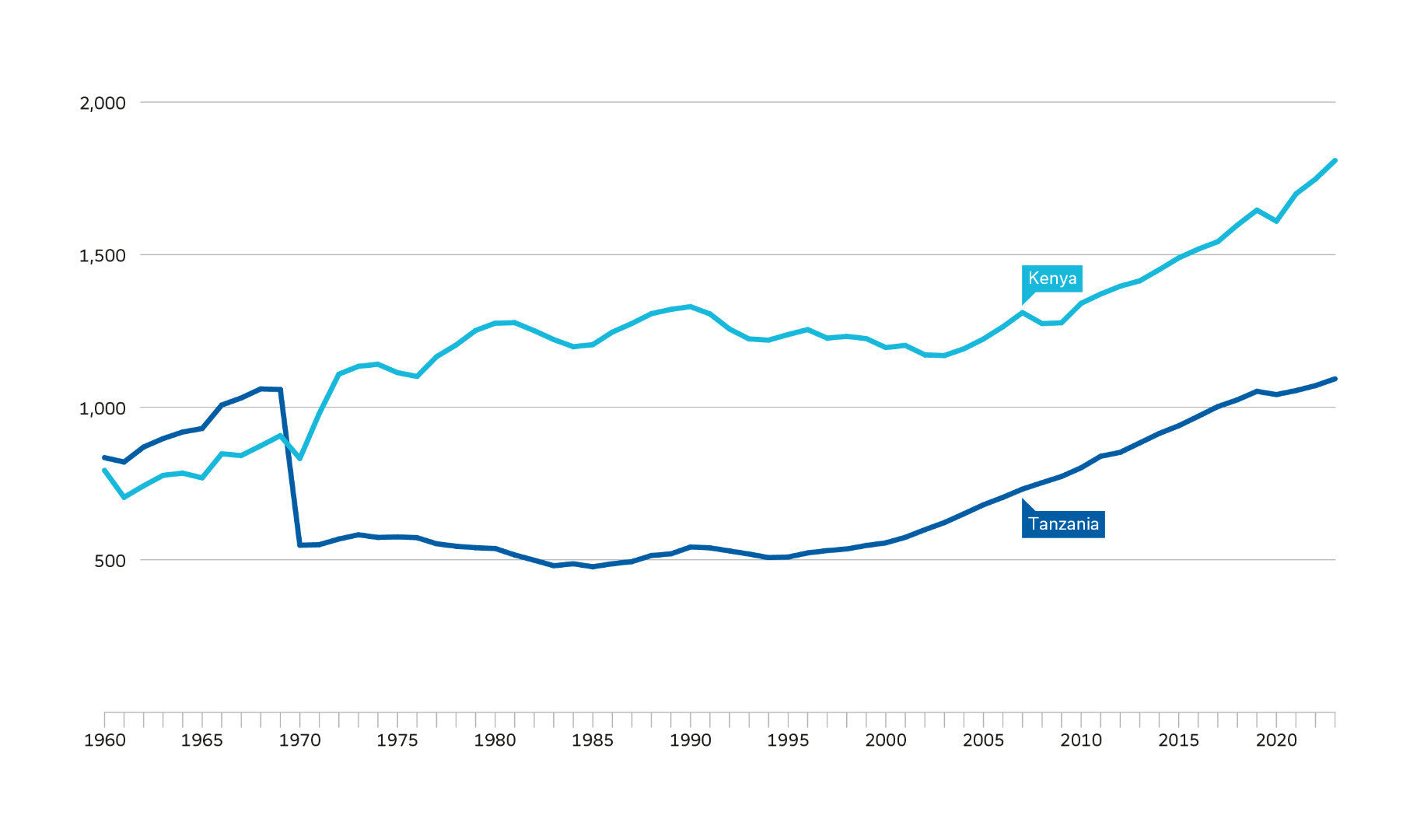

Fig. 3: Development of Per Capita Income in Kenya and Tanzania from 1960 to 2023 in US Dollars

The following examples illustrate this point vividly. When Kenya and Tanzania gained independence from Britain in the 1960s, they had similar per capita incomes, which were largely based on agricultural production. While Tanzania nationalised businesses and introduced a socialist state model under President Julius Nyerere, Kenya has pursued liberal economic policies and market-based structures since independence. Kenya’s per capita income has increased from 793 to 1,800 US dollars since 1960, while in Tanzania, it has increased from 834 to 1,092 US dollars. As a result, Kenyans are now 70 per cent wealthier than their Tanzanian neighbours.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that Kenya will become the strongest economy in East Africa in 2025. According to the IMF, Kenya has weathered the negative economic effects of the pandemic better than other countries in the region. Thus far, Ethiopia has dominated the East African economy. However, after the Ethiopian government liberalised the exchange rate of its national currency – the birr – against the US dollar last year and thereby abandoned its previously controlled exchange rate, the birr lost significant value. By contrast, Kenya’s strong performance is attributed to its open market economy and its diversified sources of income as well as to the stability of the Kenyan shilling.

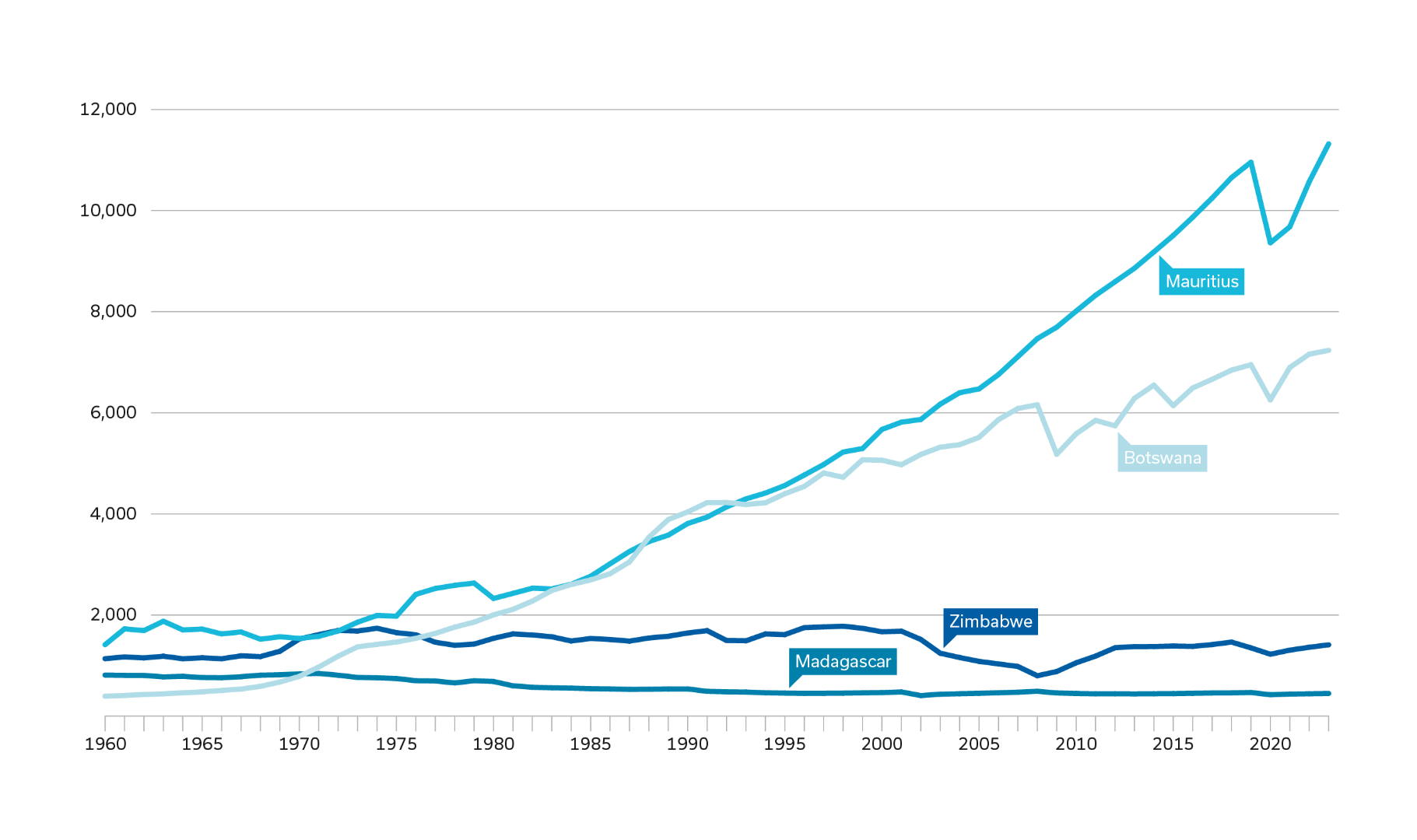

A comparison between Botswana and Zimbabwe also highlights the crucial role political decisions play in economic development. Botswana gained independence in 1966, Zimbabwe fourteen years later. At the time of its independence, Botswana was poorer than its neighbour Zimbabwe. However, Zimbabwe did not experience an economic upturn after gaining independence in 1980. Although Zimbabwe has abundant natural resources and was once known as the breadbasket of Africa, the country’s economy deteriorated severely under President Robert Mugabe: Skilled professionals emigrated, while private investors were deterred by incoherent policies, widespread corruption, land reforms and expropriations.

A small island state far from its main trading partners, Mauritius gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1968. Since then, its per capita income has increased more than sevenfold – from 1,522 to 11,319 US dollars – such that today, it has the highest per capita income in Africa. In the early 1970s, the country began a major economic transformation, moving away from sugar production – then its dominant source of income – and towards a diversified export model. Its successful development is widely attributed to a combination of political stability, strong state institutions, low levels of corruption, a sound regulatory environment and a clear focus on international trade. This development has included a liberal investment climate and generous fiscal incentives for businesses. In addition, Mauritius has the lowest tariff rates in the world. Madagascar – Mauritius’s larger neighbour – by contrast took a different path after gaining independence in 1960. It turned inward, nationalised private foreign companies and expropriated privately owned farmland. While Madagascar was considered a middle-income country at the time of its independence, it is now one of the few countries in the world that has become poorer over the past 50 years.

A blanket portrayal of Africa as an exploited continent fails to recognise the highly diverse development paths taken by individual countries. Such a one-dimensional perspective also ignores the fact that the continent’s independent states possess agency of their own – a capacity for self-determination that some have used to the benefit of their local population. Reducing the lack of economic and social development solely to ongoing global unequal power relations does not do justice to the varied experiences of African countries. It also downplays the success of those nations that – despite often-difficult circumstances – have risen to become emerging economies or – in the case of Mauritius – a middle-income country.

To argue otherwise would imply that African countries have failed in recent decades to take political responsibility for their own economic development and are merely passive objects dependent on outside powers. “However, this kind of paternalism reproduces a colonial view of Africa as a dependent continent that denies Africans any influence over their own capacity for self-determination.” The fact that Liberia and Ethiopia – the only countries on the continent that were never colonised – have experienced strikingly similar economic and political trajectories also runs counter to neocolonial theories of persistent dependency.

Fig. 4: Development of Per Capita Income in Selected African Countries from 1960 to 2023 in US Dollars

Africa’s International Relations Are No Longer Shaped Solely by the West

While Africa does not yet play a major role in global trade, African countries nonetheless maintain international economic relations and make their own decisions about whom they trade with. Global trade has long ceased to be dominated by Western industrialised nations; instead, Asian countries – most notably China – have also become major economic powers. This shift has also affected Africa’s trade relations. From 2014 to 2023, Europe’s share of African trade averaged around 27 per cent – down from 48 per cent in the 1990s. Over the same period, Africa’s trade with China and India grew from approximately 9 to 23 per cent.

Like Western industrialised countries, China mainly imports raw materials, minerals and metals from Africa and exports manufactured goods in return – such as machinery and electronics. In addition, China has invested heavily in infrastructure development across the continent over the past decade, often securing preferential access to strategic raw materials in return. Unlike the EU, however, China has thus far made little effort to promote manufacturing industries or to create employment opportunities within Africa. While the Chinese model has indeed helped many African countries to quickly develop urgently needed infrastructure, the extent to which this model has contributed to sustainable economic growth remains questionable.

Against this backdrop, it is troubling that the term “neocolonialism” is sometimes used to fuel anti-Western resentment by suggesting that the oppressed nations of Africa must be liberated from Western exploitation: After all, the global and diverse trade relations of African countries clearly show that their trade is no longer limited to Europe.

The Political Accountability of African Leaders Must Not Be Overlooked

Neocolonial theories attribute the African continent’s relative economic underperformance to external factors. Not only is this view overly simplistic and dismissive of the heterogeneity of African states, but it also ignores internal dynamics and overlooks the fact that “a lack of good governance and questionable policy choices have significantly contributed to many postcolonial problems”, as the examples of Zimbabwe and Madagascar clearly show. Indeed, as Nigerian scholar Ejike Raphael Nnamdi aptly writes, “[m]ore than 60 years after independence, one wonders why colonialism would still be seen as a scapegoat for our inactivity. Does it mean apart from colonialism and its appurtenances, as exogenous factors, no endogenous factors can be responsible for our predicament? Who takes the blame for the endogenous factors when they are present?”

In this context, it is also important to acknowledge that trade partnerships and agreements with international companies do not necessarily mean that the population at large receives the maximum benefit. This is particularly true of resource agreements, which are often negotiated behind closed doors – a practice that fosters corruption. While the exact revenue generated by such agreements remains unknown, it is clear that governments are missing out on tax income that could otherwise be used to support socio-economic development. Poor governance, corruption and mismanagement also deter potential investors as these issues can increase business costs by up to 40 per cent compared with other developing and emerging regions.

Africa’s Agency Is Growing

There is no doubt that colonisation has had negative effects on the social, societal and economic development of African countries – effects that are still felt today. It is therefore right and important that countries such as France, the United Kingdom and Germany acknowledge their colonial past, be willing to confront this history and apologise for colonial injustices. Nonetheless, African countries are no longer economically dependent on their former colonial powers and now make independent decisions concerning their trading partners. At the same time, international trade relations have contributed to growing prosperity in many African countries in recent decades – provided that these countries have used their post-independence agency to improve overall economic well-being.

As trade relations have expanded, so too has the presence of African countries in multilateral forums, such as in the United Nations, in the G20 and in BRICS, whose members now include South Africa, Ethiopia and Egypt. South Africa – which is holding the G20 presidency this year – places particular emphasis on the continent’s economic development. Issues such as industrialisation, the processing of raw materials, trade partnerships and the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can be expected to feature prominently in high-level meetings between heads of state and government throughout the year. Given the current geopolitical situation and the reduced engagement of the United States with Africa, the European Union has a real opportunity to demonstrate that it is a long-term and reliable partner for the continent – and that it supports these key priorities.

African Countries and Europe Both Stand to Benefit from Stronger Trade Relations

African countries maintain trade and economic ties with a wide range of partners, increasingly also with countries beyond Europe and the Americas. Europe would do well not to overlook this trend: From a geostrategic perspective, trade relations with Africa are becoming ever more important, not least because the future of the transatlantic partnership remains uncertain. The African Union is pressing ahead with the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area, which offers enormous potential, including for European and German businesses. In 40 years’ time, there will be more people living in Africa than in India and China combined. With the middle class on the continent growing, there will also be a growing demand for foreign goods. At the same time, AfCFTA creates opportunities for foreign companies to set up local production and to benefit from the young and expanding workforce. However, major efforts are still required in order to make the free trade area a reality – and this too should be addressed openly and honestly.

There often seems to be a lack of political will on the part of African governments to dismantle trade barriers and to open up markets. However, stronger intra-African trade could offer the continent enormous benefits: At present, intra-African trade accounts for just 16 per cent of Africa’s total trade volume – far below the levels of intra-European trade (67 per cent) and intra-Asian trade (60 per cent). Nevertheless, almost half of the goods traded within Africa are manufactured products, which indicates that once implemented, the African Continental Free Trade Area has significant potential to drive industrialisation across the continent. The uncertainty on US tariffs for African exporters as well as an unclear future of the AGOA should be a clarion call for African states to finally prioritise the expansion of internal trade. Even before the free trade area is fully realised, the EU can support the continent in implementing reforms that reduce both tariff and non-tariff trade barriers. This is also in the EU’s own interest since only then can European companies make their operations in Africa more profitable.

However, it is not only Africa’s export markets that are set to grow in importance: Indeed, the continent’s natural resources will do so as well. Many of the strategic minerals and metals needed worldwide for the energy transition and for low-carbon technologies can be found in Africa. There is global interest in securing access to these raw materials, in some cases under questionable conditions. China has often secured access to critical raw materials whose value far exceeds that of the completed infrastructure projects provided in return. A “minerals for security” agreement between the United States and the Democratic Republic of the Congo grants US companies preferential access to mineral deposits, while in return, the US pledges military support to help end the ongoing violent conflict in the country. In West Africa, with financial support from the US, the American company Ivanhoe Atlantic plans to expand the Liberty Corridor between Guinea and Liberia – a project that will not only improve the infrastructure of both countries, but also significantly facilitate the transport of iron ore from the company’s mines in the region.

African countries are in a strategic position and can use the global interest in their raw materials to their own advantage – something that further undermines the neocolonial view of Africa as a passive actor. Europe, too, should secure its seat at the negotiating table, define its economic interests more clearly than in the past and emphasise that both sides stand to benefit from strengthened trade relations.

– translated from German –

Anja Berretta is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Regional Programme Economy Africa, based in Nairobi.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.