Issue: 3/2021

“Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or news-papers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” In 1787, these words by Thomas Jefferson, third president and one of the founding fathers of the United States, underlined the importance of the press. More than 230 years later, freedom of the press is one of the key pillars underpinning a free society – but is still not the norm in many parts of the world. On the contrary, it has been declining steadily for years. Press freedom and media professionals needs to be actively defended worldwide and, unfortunately, Europe is no exception here. Afterall, the erosion of press freedom is both a symptom of, and contribution to, the collapse of other democratic institutions and principles. That is why these developments are so alarming.

On the other hand, quality media have regained trust and relevance over the past year. COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of accurate health information and reliable reporting, and a new awareness of the value of independent media for society as a whole has emerged.

Ideal vs. Reality: Press Freedom as a Human Right and the Current Situation Worldwide

The concept of “freedom of the press” as a medium’s independence from influence and directives is a relatively new one. The idea began to evolve during the Enlightenment – a transition from the darkness of the Middle Ages to the light of knowledge – and was first introduced in England at the end of the 17th century when censorship was abolished. In the US, the Constitution’s First Amendment has officially protected freedom of the press, religion, speech, and assembly since 1789. In Germany and the German-speaking countries, however, it took almost another one hundred years to protect media products. It was only with the passing of the Imperial Press Law in 1874 that freedom of press was first uniformly regulated by law in Germany, though its effect was short-lived: only four years later, it was repealed by the Anti-Socialist Law. From 1933 to 1945, the press was forced to toe the party line under the National Socialists. In today’s Federal Republic, Article 5 of Germany’s Basic Law guarantees freedom of the press, along with freedom of opinion, freedom of broadcasting, and freedom of information.

In Europe, these freedoms are also protected under Article 10 of the Council of Europe’s European Convention on Human Rights. Within the European Union, freedom of expression and freedom of the media are also guaranteed for all Member States in Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Since 2000, this Charter has brought together all the civil, political, economic, and social rights of European citizens (and has been legally binding since the Treaty of Lisbon’s entry into force on 1 December 2009). This guarantee is one of the key criteria for candidate countries wishing to accede to the Union.

Unfortunately, however, these legal bases do not prevent threats to freedom of press on the continent of Europe. Quite the opposite: according to an assessment by Reporters Without Borders, many members of the Council of Europe present serious shortcomings regarding freedom of press. The situation in Ukraine, Georgia, and Armenia is “problematic”, while that of Turkey and Russia is described as “bad”. Azerbaijan comes in last among members of the Council of Europe, ranking 167th out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders report.

According to that organisation, the situation is also “problematic” in all the candidate countries of the Western Balkans (Northern Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, and Montenegro) as well as in the potential EU candidate countries Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. This is also confirmed by the European Commission’s reports on candidates for accession to the EU, which assess their progress towards freedom of expression and freedom of press as very poor or virtually non-existent.

Within the European Union, Bulgaria stands out particularly negatively as the only country ranked “bad” (112th out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders ranking). The main problem here is that most media outlets are concentrated in the hands of a few owners who coordinate with ruling politicians to set the editorial line. Meanwhile, independent media are thwarted by official harassment involving tax procedures or fines. In other parts of Southeast Europe, too, politicians and media companies are similarly intertwined, which raises concern. Other problems include unattractive working conditions for journalists, legal deficiencies, and weak self-regulation by the industry. Journalists are increasingly the target of attacks, threats, and insults. During the coronavirus pandemic, many countries have also attempted to push through restrictive laws curtailing journalistic freedom. Therefore, the European Commission’s 2020 Rule of Law reports on Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia also address the media situation. The European Commission levels criticism against the lack of transparency in media ownership, the role of state advertising, the lack of independence of regulatory authorities, systematic political pressure, restricted access to public information, and attacks on journalists. The EU’s Eastern states are experiencing problems as well. In Poland, the state and media companies are intertwined in the structure of media ownership. Late last year, the state oil company PKN Orlen acquired the publishing house Polska Press, which owns many regional newspapers. Press freedom is also under pressure in Hungary.

Digital surveillance presents a growing problem for journalistic freedom. In July 2021, this issue increasingly attracted headlines in the wake of reports about Pegasus spyware. At a recent event of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Christian Mihr, Executive Director of Reporters Without Borders, reported that half of all journalists who contact his organisation for help now do so on account of digital surveillance. This has led Reporters Without Borders to establish a digital forensics laboratory.

In July, another sad piece of news on press freedom in Europe shook the world: the murder of Dutch journalist Peter de Vries, a specialist in organised crime reporting. Unfortunately, this is not the first time a journalist has been murdered on European soil. Let’s not forget Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Anne Caruana Galizia, who was killed by a car bomb in 2017, and Slovak journalist Ján Kuciak, who was shot dead in 2018. They had also reported on corruption and organised crime, respectively.

A particularly sensational murder was that of exiled Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey in 2018. Like many Middle Eastern countries, Saudi Arabia languishes at the bottom of freedom of press rankings. Here, censorship is the order of the day. The situation is also alarming in Libya, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Egypt. Egypt is one of the countries with the most imprisoned journalists. According to the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Barometer, 28 journalists were behind bars in Egypt as of August 2021, compared to 342 worldwide.

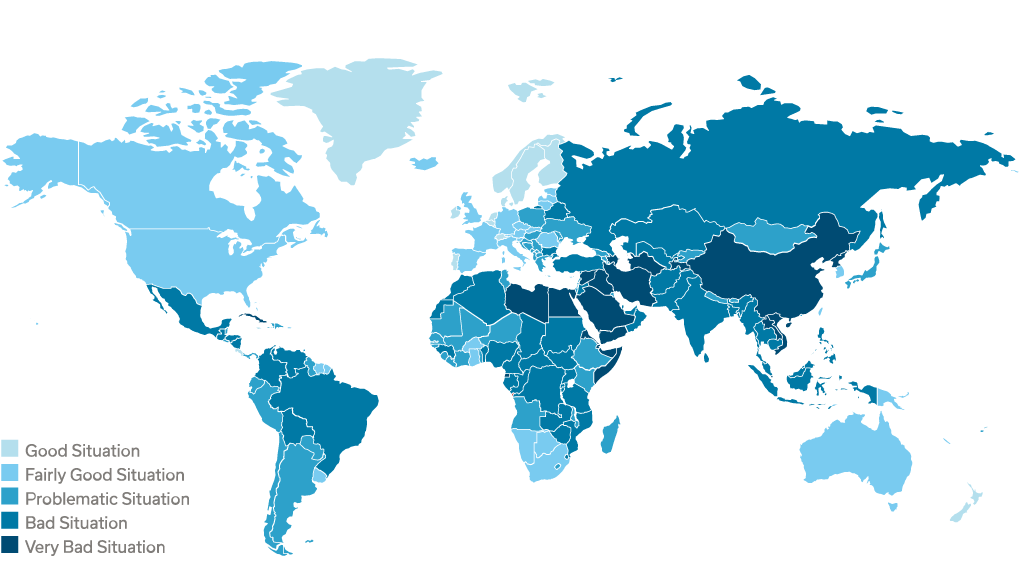

Fig. 1: Freedom of the Press Worldwide in 2021

Source: Own illustration based on Reporters Without Borders 2021: The categories in the World Press Freedom Index are as follows: “Very Bad Situation”, “Bad Situation”, “Problematic Situation”, “Fairly Good Situation”, and “Good Situation”. Reporters Without Borders 2021: The World Press Freedom Index, in: https://rsf.org/en/world-press-freedom-index [8 Aug 2021].

This is hardly surprising given that Article 32 of the Arab Charter on Human Rights guarantees freedom of expression and the right to information on the one hand, while listing a plethora of exceptions to it, on the other. At any rate, Egypt is one of many countries around the globe that is still far from realising the ideal set out in Article 19 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Against this backdrop, it was in June 2017 that the German Bundestag called upon the United Nations to appoint a UN Special Representative for the Safety of Journalists in order to make lasting improvements to the situation of journalists. This is important because the freedom to inform and be informed is also a yardstick for respecting other human rights. This certainly applies to the world’s most populous country: China.

A Global Propaganda Machine: China’s View of the Media

The concept of freedom of press as it is interpreted in the West does not apply in China, where there is a total lack of freedom. All reporting is centrally controlled, and expressions of opinion are subject to censorship. The internet is monitored with particular rigour. Foreign journalists face numerous obstacles. The situation has further deteriorated over the last two years. Major US media operations have been reduced to one-man shows since many of their journalists were unceremoniously expelled in March 2020. Another major blow to freedom of press that commanded much international attention was the closure of Apple Daily, a Hong Kong newspaper with a leading voice in the democracy movement. Its closure coincided with the first anniversary of Hong Kong’s National Security Law. After founder Jimmy Lai was arrested and sentenced to 20 months in prison back in the summer of 2020, the closure led to more journalists being imprisoned on charges of violating the National Security Law. It is little consolation that the paper had its largest-ever circulation on its last day of publication. According to its own figures, it sold one million copies instead of the usual 70,000.

At the same time, China is heavily investing in foreign media, working full steam to expand its role in the global media ecosystem and develop the country’s ability to control narratives. This is backed by the global presence of Chinese media through foreign state broadcasters and the foreign-language TV station CGTN, along with a Chinese campaign that above all seeks to contrast “negative Western coverage” of China’s global engagement with positive coverage. African countries play a key role in this respect. China has many economic interests on the continent, while also enjoying more favourable public opinion in Africa than elsewhere. The leadership also maintains friendly relations with many African nations and their political elites, making the continent fertile ground for China to experiment with foreign policy tools, including media cooperation.

Another instrument is training, which imparts journalistic expertise in line with the Chinese concept of reporting, which is tantamount to propaganda. In this way, Xi Jinping seeks to not only control the narrative inside and outside China but also to use this expansion to establish China’s own norms and standards. The triad of censorship, intimidation, and control of the narrative is what makes the Chinese model so dangerous. Overall, a disparity prevails between the elites: while Chinese elites are well-educated and well-versed in the languages and culture of Western countries, very few people in Europe speak fluent Chinese or are familiar with its classic literature. It is, therefore, vital to engage with China in a more strategic way so as to counter its aggressive desire to control the narrative and shape opinion, and to stand up for facts, free societies, and media freedom.

Alongside political pressure, a deterioration of the global media situation can also be attributed to economic reasons. The pressure on newspapers, radio, and television is continually growing because of the inexorable rise of online media and social networks. Mainstream media are also struggling with dwindling trust – a trend that, fortunately, has been halted somewhat by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Light and Shadows: COVID-19 and its Repercussions for the Media Landscape

As in many other areas of life, COVID-19 has left its mark on the global media landscape, making it far more difficult for journalists to exercise their function as watchdogs and providers of information. Recurring lockdowns restricted their freedom of movement and hence their ability to research stories. Using the smokescreen of combating fake news, autocratic governments have attacked freedom of press, and certain political leaders have used the pandemic as an excuse to censor unfavourable reporting and arrest critics.

Once again, China stands out in this respect. Chinese authorities have deployed a combination of low- and high-tech tools to not only manage the coronavirus outbreak but also to prevent internet users from sharing information from independent sources and challenging the official narrative. Freedom House attests that China’s regime is the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom for the sixth year in a row. Tracing apps and digital health scores are another way of normalising the kind of digital authoritarianism that the Communist Party aspires to.

On this side of the second Chinese wall, the Great Firewall, internet freedom is also threatened by censorship and surveillance. Facebook, Instagram, et al. have long been major sources of information – sources that are forcibly dried up from time to time. Many countries have introduced restrictive online laws under the guise of combating fake news. Governments in at least 28 countries have censored websites and social media posts to suppress unfavourable health statistics, allegations of corruption, and other COVID-19-related content. Others have quite literally pulled the plug – in more than 13 countries, including India, the world’s largest democracy, total internet shutdowns lasting for days at a time were no rarity in 2020.

On the other hand, the media have gained trust and relevance during the pandemic. A new awareness of the value of independent media has emerged. For example, Africa has moved away from the freebie mentality. Although a few years ago, people were convinced that paywalls would never work in Africa, the pandemic has demonstrated that readers are prepared to pay for quality journalism. The winners to emerge from the crisis have been young media outlets that were already pursuing a clear digital strategy and no longer dependent on advertising for their survival.

The scientification of the public discourse that has accompanied the pandemic seems to strengthen fact-based discussions – a welcome development after years of media bashing à la Donald Trump. In Asia, for example, small, independent media companies providing reliable information have gained momentum. In Sub-Saharan Africa, innovative formats have emerged that also enhance the quality of journalism. Although pseudo journalism and fake news are primarily disseminated via the internet, many regions and countries – not least in Germany – have seen a growing demand for fact-based, reliable reporting, which affords an opportunity for quality-oriented media to regain the trust of its audience.

This has also resulted in an increase in digital subscriptions. In general, as in so many other areas, the COVID-19 pandemic has led the media to push ahead with its digital transformation. Latin America is the only region that (still) lags behind, mainly because of its poorer internet access.

Economic difficulties faced by most of the world’s media companies have been exacerbated by the pandemic, albeit with certain differences. In Eastern Europe, for example, pro-government media companies continue to benefit from state-sponsored advertising, while other media outlets have suffered even greater losses. In many parts of the world, media outlets have expanded their online presence to partially compensate for these losses by introducing additional paywalls. Small, independent media companies in Asia and Central Eastern Europe have managed to increase their revenues through growing subscriber numbers. Nevertheless, journalists’ livelihoods are threatened by pay cuts or a complete loss of wages. In Africa, thousands of journalists have lost their income. Buyouts of ailing media companies by Chinese investors are increasing as more and more traditional media companies declare bankruptcy.

To sum up, the media faces a broad array of difficulties. Independent reporting becomes even more challenging under these adverse conditions. Against this background, and as part of its worldwide support for democracy, the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung places particular emphasis on supporting a free and independent press as a prerequisite for opinion formation in a democratic system. Through our three media programmes in Asia (based in Singapore), Sub-Saharan Africa (based in Johannesburg) and Southeast Europe (based in Sofia), we are working to strengthen independent and diverse media landscapes. Our aim is to help the media develop professional journalistic standards, provide young journalists with the best possible support as they progress in their profession, and advocate and promote the importance of the media as an integral part of democratic and free societies. Unfortunately, much remains to be done.

– translated from German –

Katharina Naumann is Desk Officer for International Media Programmes at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.