The EU has faced many crises in the past and always overcome them – but the current sovereign debt crisis is of a very different dimension. Many EU member states are hugely in debt and have been forced by the financial markets to adopt very tough austerity packages. This in turn has led to a backlash against incumbent governments (France, Spain, Greece, Netherlands, Italy, Ireland, Slovakia) and a rise in support for extremist parties usually opposed to the European project.

The crisis is also affecting the EU’s pretensions to be a global actor. The first casualty is the time available for foreign policy. EU leaders are devoting 90% of their time to economic and financial matters with a consequent reduction in time available for foreign policy. The EU had to postpone an important summit with China last October because of an emergency meeting of the European Council.

A second problem is the resources available for foreign policy. The EU’s budget for external affairs is unlikely to be increased as member states look to cut spending. Several foreign ministries have had to take big cuts eg 50% in the case of Spain. Any further cuts would seriously impact on the EU’s pretensions to play a global role.

A third potential problem is access to the EU’s market. There are many voices calling for protection against ‘unfair competition’ from third countries. It will be important to maintain an open EU market albeit access based on reciprocity as regards its strategic partners.

A fourth factor is the damage to the EU’s image as a well-governed entity, an important basis for the EU’s attraction as a soft power. Restoring the EU’s economic health would of course help repair the damage to its image.

Fifth, the US global footprint is set to decline due to budget cuts. This means that the EU will have to take more responsibility for its own security and regional security. Furthermore, ensuring the continuation of a strong liberal world order that emerged after the Second World War remains a key European interest. It is essential that emerging powers become stakeholders in that order.

Until the Second World War European states dominated international relations. Arguably the US had become a major player after the First World War but it retreated into isolationism for most of the inter-war period. Between 1949 and 1989 the Cold War was the dominant security paradigm for Europe. The US and the Soviet Union were the two global superpowers vying for power and influence around the world. In these circumstances Europe was unable to assert itself as a global actor. European integration developed under the security umbrella of the US, which from the beginning was generally a strong supporter of a more cohesive Europe. In many ways the integration process was about abolishing traditional foreign policy. Indeed, the process of integration was largely about developing a new form of security, based on sharing sovereignty that was unique in world history. The success of the integration process and the growing economic power of the EU were important factors in propelling the EU to be a more forceful global actor. The move towards globalisation in the 1980s and 1990s also blurred the lines between traditional foreign policy and other aspects of external relations. But it was the collapse of communism and the resulting unification of Germany that were the main factors in moves to establish a common foreign and security policy (CFSP).

The failure of the EU to prevent the conflict in the Balkans was a reality check on the more ambitious advocates of the CFSP. But the Balkans disaster propelled the Union to build up its crisis-management tools, including a robust civil-military, peace-keeping capability. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 brought another profound shift in attitudes to international relations. This was not a state attacking another state but a global terrorist network striking at the heart of the world’s only superpower. Terrorism subsequently became the defining security paradigm for the US with consequences for the EU and all allies of the US.

The last decade has also witnessed a developing global consensus on the main security threats, even if there are differences in approach to tackling these threats. These include failed states, nuclear proliferation, climate change, cyber crime, terrorism, regional and ethnic conflicts. But citizens are also concerned about transnational threats including health pandemics (Asian flu), environmental disasters (tsunami), organised crime (drugs, people smuggling) and illegal migration. It is evident that no one state, no matter how powerful, can tackle these threats on its own. It is equally evident that the military instrument alone is inadequate to deal with these threats.

This is where the EU has a certain advantage in that it can bring to the table an impressive array of civilian and military instruments to tackle these problems. It can engage in political dialogue, impose sanctions, offer trade concessions, lift visa restrictions, provide technical assistance, and send monitoring missions and even troops if required

Superpower EU

The former British prime minister, Tony Blair, once said that the EU should be a superpower but not a superstate. Some might regard the EU already as a superpower in some areas such as trade policy. Clearly it is not a military superpower like the US and has no ambitions to develop in that direction. But what kind of actor is the EU? There are many kinds of actor on the world stage. The vast majority are nation states (189 at the last count) nut international organisations (UN, IMF, NATO) and large corporations (Google, Siemens) and foundations (Gates, Soros) are also important actors. It is certainly true that the US is in a class of its own in terms of the ability to project military power, but military power alone is rarely sufficient to resolve sensitive political problems. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were a sobering experience for many in the US who believed in the supremacy of the military machine. In the Middle East the US has struggled for over forty years without success to find a solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Under President Obama it was reluctant to take the lead role in policing the no-fly zone over Libya authorised by the UNSC in March 2011. Nearer to home the US has not been able to secure a peaceful, democratic Haiti, nor has it been able to impose its will on countries it regards as ‘difficult’ such as Cuba or Venezuela. The financial crisis that engulfed the US in 2008 has also significantly reduced its global standing. Is American capitalism still the shining model for the world?

The other permanent members of the UNSC – Russia, China, Britain and France – are also important nation-state actors, but none has the global reach of the US. Russia, the largest country in the world, remains in a weak state twenty years after the collapse of communism. China has increased its global presence significantly in the past decade as a result of its very high growth rates. But it also has major internal problems such as corruption, environmental damage and uneven regional development to overcome. South Africa, India and Brazil are also global actors but they, too, have huge internal problems to overcome.

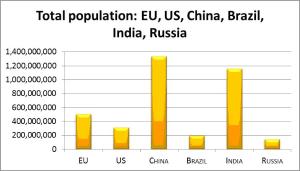

See Table 1: Population comparison (Source Eurostat)

Size is not everything. Small states such as Switzerland, Israel, Norway or Singapore can play a disproportionate role owing to their skilled population and technological prowess. Some states such as Iran or North Korea have also become important because of their desire to acquire nuclear weapons technology. Others such as Saudi Arabia and Nigeria are important because of their possession of vast quantities of oil or gas.

Britain and France are the only two EU member states that have permanent seats on the UNSC. It is evident that Britain and France bring more to the table in terms of military capabilities than Malta or Estonia. But even London and Paris were forced to pool military capabilities in a ground-breaking agreement in October 2010. Poland has more knowledge about and a greater interest in developments in Ukraine than Italy and aspires to play a regional leadership role. Similarly, Spain and Portugal are more closely involved in Latin America than most other member states; the same is true for Austria, Hungary, Slovenia and Greece with respect to the Balkan region. Thus, within the EU there are different categories of actor depending on the country’s size, military and diplomatic capabilities, experience and interests.

Other actors

The international stage also contains many other kinds of actor. For example, there are major companies such as Shell or Microsoft, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Amnesty or Greenpeace, and media organisations such as the BBC or Al Jazeera that also play a role in global politics. The presence of the world’s media can influence whether a crisis receives the attention of politicians – the so-called ‘CNN factor’. Several Middle Eastern governments sought to curtail media reporting of the huge demonstrations in Egypt and Tunisia in February 2011. The large oil companies often play a significant role in the politics of oil-producing countries. One American company, Wal-Mart, with a turnover of $485 billion in 2010, enjoys greater revenues than the combined gross domestic products of Belgium, Austria and Greece. Large European companies such as Renault and Siemens also have higher revenues than several EU member states. Human rights and environmental organisations can hold governments to account and influence world public opinion. The land-mines treaty would probably not have been signed without pressure from NGOs. Animal rights organisations have had an impact on public perceptions of countries such as Canada and Japan which engage in the culling of seals and whale fishing

Defining the EU

There are thus many different kinds of actor in world politics, but how to define the role of the EU? Clearly it is not a state such as Britain or Italy. It has no prime minister to order troops into war, yet there are thousands of EU soldiers engaged in various peace-keeping and crisis-management operations around the world. The EU has no seat at the UN yet it is the strongest supporter of the UN system, and its member states increasingly vote together in New York. In other areas the EU is a direct actor. It is an economic giant, the largest supplier of development and technical assistance in the world. Its internal market is a magnet for foreign investors and for the EU’s neighbours that desire access to a rich market of nearly 500 million citizens. It negotiates as one in international trade negotiations. It has taken a lead in the negotiations on climate change (Kyoto Protocol) and on the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the face of strong opposition from the US. It seeks to expand its value system (e.g. promotion of democracy and human rights, abolition of the death penalty) and its own rules and norms in negotiations with third countries by imposing conditions on them. It also drew up a set of conditions (Copenhagen criteria) in 1993 that had to be met before new countries could join the EU. These policies have given rise to the notion that the EU is a ‘normative actor’ in international affairs. The EU is thus a strange animal, not quite a state but with more powers than many nation states in the international system. It is increasingly recognised as an actor by third parties, and this is important for its own prestige and ability to act.

Economic giant

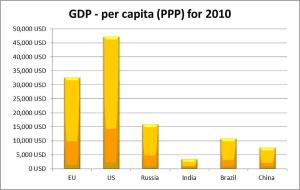

Much of the EU’s power derives from its economic strength. Its gross domestic product is slightly larger than that of the US, twice as big as Japan or China and ten times bigger than Russia’s. With nearly 500 million citizens with high levels of spending power, its internal market is crucial for many countries around the world. The EU is the biggest exporter of both goods and services. The advent of the euro has also increased the EU’s standing in the world. It is the second largest reserve currency in the world (with roughly 30 per cent of global reserves compared to the US dollar, about 60 per cent). More and more countries are using the euro either directly or indirectly. The eurozone could increase from seventeen to twenty or thirty countries within a decade. There are also more European firms in the top 150 of the Fortune 500 than American. Airbus has become a global leader in aircraft design and sales, while European banks, insurance companies and telecom operators have carved out a global presence. BMW, Nokia, BP, Siemens, Burberry and Hermès are just a few of the many European global brands. Europe has also taken a lead in sustainable development, with far greater attention to energy efficiency and environmental issues than other major centres of economic power. But the EU cannot afford to rest on its laurels. Its productivity rates are considerably behind those of the US (although the figures are disputed), and it spends far less on research and development (R&D) than the US or the rising Asian powers. Its growth rates are way below those for China and India as well as the US. Its leading universities struggle to match those in the US. Overall, however, the EU’s economic strengths have contributed to its growing assertiveness as a major player in international economic and financial matters.

See Table 2: GDP per capita comparison (Source Eurostat)

Public diplomacy

How do you sell the EU? What is the EU brand? How do citizens both inside and outside the EU view this strange animal? Very few citizens could name the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission or the President of the European Parliament. How do you distinguish between those things that are quintessentially European like the Eurovision Song Contest or the Champions League and national images, whether of Mozart or Picasso, French cheese or German cars that equally are part of European culture and tradition? Only rarely does a European team take on other opponents. The biennial Ryder Cup between the best European and American golfers is a rare example of European identity in the sports arena. London and Paris were rivals for the 2012 Olympic bid, but increasingly there are consortia of two or more European countries bidding to host major sports events. Poland and Ukraine are jointly hosting the 2012 European football championship. The EU is certainly not an easy sell, mainly because of complicated structures and its image of grey men in suits engaged in endless rounds of negotiations. This does not make for good television; and, despite their qualities, neither the President of the E uropean Council, Herman van Rompuy, nor the President of the Commission, José Maria Barroso, perhaps the two most important EU public figures, are likely to attract large audiences. Catherine Ashton has struggled to gain name recognition despite being the first EU High Representative and Vice President of the Commission. There is no doubt that the EU has to be sold in the first instance by member-state governments. The EU institutions and their leaders only have a supporting role to play. This has been the clear lesson of the various referendum campaigns that have been held in Europe over the years.

External representation

To describe the EU’s external representation as confusing would be a huge understatement. If it were an individual, the CFSP would have long been enclosed in a psychiatric ward with doctors assessing how it could have survived so long with such a deep split personality. Its schizophrenia was programmed in the pillar system set up at Maastricht and was further complicated by the addition at Amsterdam of the post of Secretary General/High Representative (SG/HR) for the CFSP. The EU’s external representation currently varies between different policy areas: the CFSP, trade, financial, economic, environmental and development affairs. The advent of Catherine Ashton and the external action service (EEAS) was supposed to help the EU become more consistent, coherent and visible in foreign policy. This remains a work in progress.

Despite the introduction of the euro, the EU continues to punch below its weight in international financial institutions (IFIs). With the shift, in eurozone countries, of monetary policy sovereignty from national level to the European Central Bank (ECB), the EU’s role in international economic and financial governance has increased significantly, although there are still problems stemming from the non-membership of some member states in the eurozone and jealousies surrounding participation in G8 meetings. The G8 and G20 formats do little to help EU coherence and visibility. The current arrangements whereby there are eight European seats at the G20 table are scarcely defensible.

Scorecard 2011

Each year the European Council on Foreign relations publishes a scorecard on the EU’s performance. In 2011 it gave low marks to the EU for despite some successes with regard to the successful intervention in Libya, the relatively smooth entry of Russia into the World Trade Organization, and the agreement reached at the Durban conference on climate change. But, it argued, ‘the out-of-control debt crisis has started eroding Europe's foreign-policy tools and degrading its leverage with other powers like China.

It pointed to EU’s relative failure to follow through on its promise of ‘money, markets, mobility’ to the new governments in North Africa. Budget constraints limited the money the EU was prepared to offer to 5.8 billion euros in direct funding; populist fears about immigration restricted offers of greater mobility for students and workers; and protectionist sentiment, fueled by economic difficulties, precluded any real opening of markets, especially to North African agricultural products.

As regards China it suggested that cash-strapped member states sought to secure investment rather than open Chinese markets and independently petitioned Beijing to buy their sovereign bonds. As a result, while the European Commission made valuable efforts to open up China's public procurement markets and ensure access to rare-earth minerals, Brussels often fought alone on these issues while member states individually sweet-talked Beijing and prioritized their bilateral ties.

More generally, it alleged that Europe's deteriorating economic position has taken a toll on budgets for aid and defence, a trend that will probably continue and even intensify. This raises questions about whether Europeans will be able to maintain their role in crisis management around the world, let alone undertake serious military interventions like the one in Libya, where the difficulties of waging a modern war with limited casualties made American "leadership from behind" indispensable. Even worse, although member states discussed "pooling and sharing" military resources, in practice they cut their defence budgets and capabilities without cooperation or consultation with partners (or, for that matter, with allies in NATO), thus amplifying the effects of the cuts.

Conclusion

The EU has developed steadily as an actor in international affairs and today is widely recognised as playing an important role in many different policy areas. More and more governments and media organisations are demanding ‘the EU view’ on international issues rather than the views of twenty-seven member states. Indeed, the enlargement of the EU has increased these demands, and where appropriate there is an EU view, usually put forward by Catherine Ashton, officially called the EU’s High Representative for the CFSP but more often described as ‘EU foreign policy chief’. But the EU still has many problems to overcome if it wants to be a more coherent, more visible and more influential global actor.

The EU stands for strengthening the institutions of global governance through its aim of ‘effective multilateralism’. But this is not so easy to implement when there are rivalries and jealousies between the member states, especially in how the EU and member states seek to represent themselves in international bodies.

There is little likelihood of the EU having its own seat on the UNSC in the near future, but there is much the EU can do to support the UN. Following enlargement to twenty-seven member states there is growing pressure from third countries for the EU to reduce its seats in various bodies or to speak with one voice. But it is not only foreign ministries that are involved in such decisions; prime ministers and finance ministers also want their say.

The biggest problem facing the EU, however, is resolving the sovereign debt crisis. This is having a negative impact on the external relations of the EU. If the EU is to continue to have serious pretensions to be a global actor then overcoming the crisis is a sine qua non.

This article was written by Dr Fraser Cameron for the Portuguese Language "Cadernos Adenauer", which is published four times a year by the Konrad Adenauer Brazil Office.

Fraser Cameron is a former European Commission advisor and well-known policy analyst, author and commentator on EU and international affairs. He is Director of EuroFocus-Brussels and an Adjunct Professor at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin.

For technical reasons, references only available in the PDF Version