Issue: 3/2025

- Japan is widely regarded in Asia as a trustworthy partner whose development cooperation promotes self-reliance rather than dependence. Increasingly, that development cooperation must be viewed within the context of Tokyo’s strategic rivalry with China.

- While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for planning and coordination, implementation is handled primarily by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Japan concentrates its development cooperation more heavily than most donor countries on a small number of Asian partner states, with a strong focus on infrastructure projects.

- In addition to fostering sustainable development in its partner countries, Japanese development policy also aims to cultivate a favourable international environment that serves Japan’s own security, development, and economic interests. At the heart of this strategy lies the so-called Trinity Approach – a three-pronged model based on aid, trade, and investment.

- Japan has been significantly more successful than Germany in aligning development cooperation with the interests of its own economy. Tokyo often relies on tied aid arrangements, which require recipient countries to award development project contracts to Japanese companies.

When Japanese politicians travel abroad for government consultations, they are welcomed as respected guests. A recent survey in ASEAN countries found that nearly 60 per cent of respondents consider Japan the most trustworthy country in Asia. Indeed, the country is seen “as a supportive partner, fostering self-reliance rather than dependency”.1 This strong international reputation goes hand in hand with economic advantages: According to the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), Japan’s economic net benefit from official government delegations between 2001 and 2020 amounted to 53 billion US dollars – an average of 2.6 billion US dollars per year.2

A substantial share of these business deals can be traced back to Japan’s development cooperation. In 2023, RIETI reported that 17 per cent of all overseas infrastructure projects awarded to Japanese companies between 1970 and 2020 were funded through official development assistance (ODA). The Japanese economy benefited most when infrastructure projects were supported by a combination of loans and grants. Grants could be used in advance, for example, to fund feasibility studies on the opportunities and risks of an investment, thereby generating “goodwill effects” for Japanese companies – even before Tokyo enters the competition for an infrastructure project with an ODA loan.3

Saori Ono and Takashi Sekiyama do not dispute the positive impact of development cooperation on the Japanese economy but argue that ODA plays only a supportive role in the early stages of foreign direct investment (FDI). Looking at the period from 1990 to 2002 – a time when Japan saw a sharp rise in FDI – the authors identify three possible explanations:

- Information about the recipient country’s business environment was passed exclusively to Japanese companies via official development cooperation,

- the presence of development cooperation in the recipient country reduced Japanese companies’ perceived investment risks, and

- through development cooperation, recipient countries became familiar with Japanese business practices and regulatory frameworks.4

Definition, goals, and “philosophy”

According to the revised Development Cooperation Charter (DCC), which was updated in mid-2023, development cooperation in Japan is defined as “international cooperation activities that are conducted by the government and its affiliated agencies for the main purpose of development in developing regions”.5 Under this definition, any activity financed with ODA funds is considered development cooperation. Other forms of official development finance – such as concessional loans to multilateral institutions (so-called other official flows) and private flows, including direct investments and export credits with maturities of over one year – are categorized separately.

The stated goals of Japan’s official development cooperation include freedom, peace, stability, the rule of law and the protection of human rights, “human security”, poverty alleviation, digitalization, health, education, inclusion, equality, transparency, fairness, trust, environmental protection, and climate change mitigation. Development cooperation is additionally intended to promote “self-reliant development through support for self-help efforts by developing countries”6 – including through “South-South and triangular cooperation initiatives”.7

At the same time, Japan’s development cooperation is expected to foster “a favorable international environment for Japan”8 and to “contribute to the realization of national interests”.9 These interests include “securing peace and security for Japan and its people and achieving further prosperity through economic growth”.10 In dialogue with partner countries, the aim is the “co-creation of social values”. This collaborative approach is intended to help Japan develop “solutions for its own economic and social challenges and to its economic growth on a domestic level”.11 Using concepts such as “quality growth” and “quality infrastructure”, Japan promises development cooperation “that does not involve debt traps or economic coercion, and that does not undermine the independence and sustainability of developing countries”.12

Japanese development cooperation also promotes “the consolidation of democratization”13 and commits to “pay[ing] adequate attention to the situation in the recipient countries regarding the process of democratization, the rule of law and the protection of basic human rights”.14 In the revised DCC, civil society is explicitly described as a “strategic partner” in ensuring that Japan’s development cooperation is “attuned to the needs of populations”15. However, the DCC contains no reference to political parties or political party support, nor is the word “religion” mentioned at any point.

While the current DCC marks a significant policy reset, the underlying “philosophy” of Japanese development cooperation has changed little since the 1970s. It remains rooted in the so-called request-based principle.16 Strictly speaking, this principle states only that ODA should respond to demand. However, the notion of “demand” in Japan’s case has never referred exclusively to the needs and wishes of developing countries. Instead, Japanese development cooperation has long operated within a finely balanced trinity of aid, trade, and investment. This “trinity” therefore also reflects the interests of the donor country.

At least as far back as in the early 1970s, Japanese trading and consultancy firms were already meeting with foreign partners in order to jointly develop commercial projects. During the “East Asian Miracle” period between 1965 and 1990, the Asia-Pacific region experienced faster economic growth than any other part of the world.17 The demand for power plants, dams, and logistics infrastructure – for sea, air, rail, and road transport – was enormous,18 and Japanese firms were keen to benefit. At the same time, the postwar Japanese governments had committed to reparation payments.19 As a result, large-scale foreign investments that could not be financed under market conditions – often due to high risk – were relabelled as development aid, thereby giving rise to ODA requests from recipient countries to the government in Tokyo.20 In the late 1980s, Japan briefly became the world’s largest donor country.21

Volume, organization, and responsibilities

Final figures on Japan’s use of ODA for the previous year will not be published by the OECD until the end of 2025.22 According to preliminary 2023 data23 based on the grant equivalent method,24 Japan spent a total of 19.6 billion US dollars (0.44 per cent of gross national income, GNI) on ODA. Of this total, 81.5 per cent went to bilateral assistance. Germany, by comparison, spent 37.9 billion US dollars (0.82 per cent of GNI), although its share of bilateral ODA was significantly lower, at 71.8 per cent. Among the 33 members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), including the EU, only Australia, New Zealand, Norway, and the United States allocated more than 80 per cent of their ODA to bilateral cooperation in 2023.

Containing around 2,000 employees – with 80 per cent being in Japan and 20 per cent being abroad – the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is the country’s principal implementing organization. According to OECD figures from 2022, JICA delivers just over 70 per cent of Japan’s total ODA.

A further 19 per cent is managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), with the remainder being spread across the budgets of several other ministries.25 MOFA is responsible for the planning and coordination of Japan’s development cooperation and ODA. There is no Japanese equivalent to Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In addition to its approximately 100 overseas offices, JICA also operates over one dozen domestic offices in Japan. These offices work closely with the Japanese prefectural governments. One of the responsibilities of these local offices is to “provide clear and careful explanations about the significance and outcomes of development cooperation as well as appreciation from the international community to the wider public”.26 The Japanese government acknowledges “the fact that development cooperation is funded by taxes paid by the people of Japan”.27 Public understanding and support are therefore described as being “essential to implement development cooperation”.28

While ODA is implemented by JICA under MOFA’s direction, other public financial flows are managed by various other organizations.29 In the future, both financing instruments are to be more closely integrated. The Development Cooperation Charter promises that government and implementing agencies will “work as one” in the delivery of assistance.30 Japan also intends to mobilize greater private-sector funding for more “effective” development cooperation. To that end, suitable companies are to be involved as early as during the project planning stage. JICA and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance signed an agreement to this effect at the end of 2023.31

Although not itself responsible for public financial flows, the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) also plays a role in linking development cooperation with the private sector. With 76 overseas offices in 56 countries, including five in India alone, JETRO originally focused on promoting Japan’s foreign trade. Today, however, it increasingly seeks to attract foreign companies to set up operations in Japan. JICA and JETRO regularly appear together at high-level events and government meetings,32 such as at the 5th Japan-Arab Economic Forum in July 2024. At the 8th Tokyo International Conference on African Development, which was held in Tunis in 2022, JICA, JETRO, the UN Development Programme UNDP, and the UN Industrial Development Organization UNIDO launched a partnership in order to promote trade and investment between Japanese and African private companies.33 In August 2024, Ghana’s Deputy Minister of Finance – Stephen Amoah – publicly thanked both JICA and JETRO “for supporting the Japanese private sector in establishing production facilities” in Ghana.34

Loans versus grants

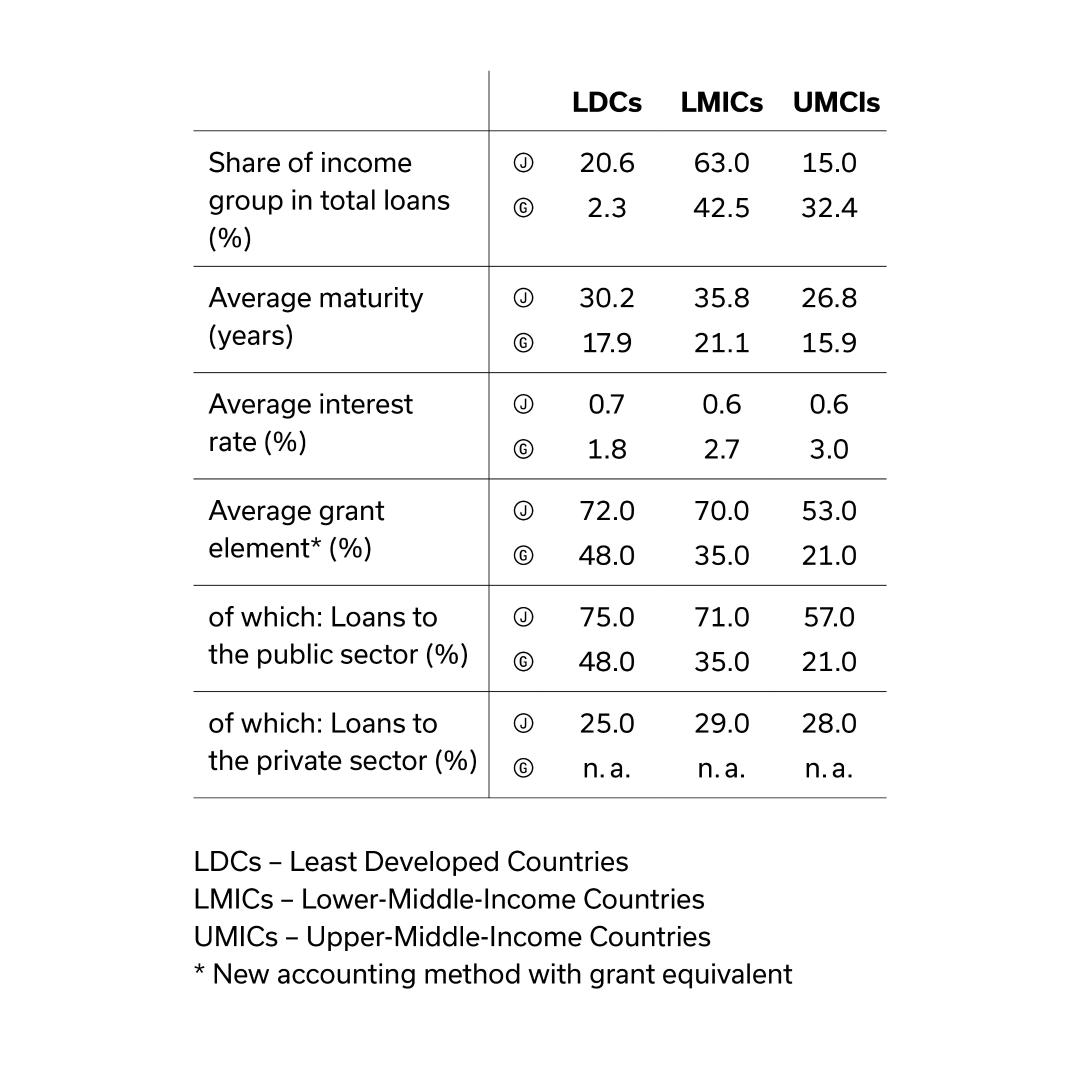

While DAC members have recently increased the share of loans in their ODA commitments – partly due to large-scale credit lines to Ukraine – the majority of ODA continues to be provided in the form of grants. Japan, by contrast, has long focused on long-term, low-interest loans as a defining feature of its development cooperation. OECD data from 2022 illustrate this situation clearly.35 In addition to loans to recipient governments, these figures also cover loans to multilateral organizations, international NGOs, and the private sector (see figure 1). Measured against the DAC average – and compared with Germany – loans play a significantly greater role in Japan’s overall ODA portfolio. In most cases, these loans are issued directly between Tokyo and the governments of the recipient countries.

Fig. 1: Average grant element of ODA loans for 2022, by channel of delivery

The average interest rate on ODA loans among DAC members rose from 0.95 per cent in 2015 to 1.89 per cent in 2022, while average loan maturity fell from 26 to 24 years over the same period. In this context, too, Japan diverges significantly from the DAC average. According to OECD data, Japan’s ODA loans to lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) in 2022 not only had a much longer average maturity (35.8 years), but also carried much lower interest rates of 0.6 and 0.7 per cent, respectively (see figure 2).

One key reason Japan strongly prioritizes lower-middle-income countries (63.0 per cent) in its loan disbursements is its use of so-called tied aid. According to DAC recommendations, this form of assistance is not permitted for the least developed countries (LDCs) and is allowed for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) only under strict conditions.

Fig. 2: Characteristics of 2022 ODA loans by income group for Japan (J) and Germany (G) (weighted averages)

Tied versus untied aid

Tied aid was long a defining feature of Japanese development cooperation and has seen something of a revival in recent years. “Tied” in this context means that only Japanese companies may be contracted to carry out infrastructure projects abroad that are financed with yen loans. The required materials and services are supplied primarily from Japan, and the maintenance of equipment and facilities is later also entrusted to Japanese providers. By contrast, untied aid allows companies from other countries to bid for project implementation contracts.

Up until the mid-1970s, nearly all yen loans were tied. Ten years later, however, this was true for only one-third of Japanese loans. By the mid-1990s, all yen loans had become untied.36 This shift was met with frustration by Japanese industry. Firms wanted to expand and use the “Trinity Approach” to open up new markets in Asia through development cooperation. In the 1990s, Japan’s export economy was also experiencing a downturn. Nevertheless, under pressure from Europe and the United States, the Japanese government was forced to reduce its tied aid to zero. Among DAC donors in the West, poverty reduction had become the dominant goal of development cooperation. Japan’s growth-oriented ODA model – focused on (tied) loans and infrastructure projects – came under growing criticism. In 200437 and again in 2010,38 DAC peer reviews recommended that the Japanese government increase the share of grants in its aid portfolio and step up its poverty reduction efforts. Then, China entered the picture.

Beijing adopted the core elements of Japan’s “Trinity” model, applying the approach of tied loans and large-scale infrastructure projects to its Belt and Road Initiative, thereby promoting its own external economic interests and – to the frustration of the United States – steadily expanding its international influence beginning in 2013. By 2016, when China secured a 99-year lease on Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port in return for debt relief, it had become clear that the initiative also served strategic interests that extended beyond the South China Sea to include the control of sea lanes and trade routes.

Japan was initially faced with the challenge of distinguishing its ODA from China’s and making it more competitive.39 With weak economic growth and high levels of public debt, increasing the share of grants was not an option. Tied yen loans then came back into fashion. In order to offer an attractive alternative to China while also avoiding renewed criticism for investing too much in economic growth and too little in poverty reduction, Japan launched its Quality Infrastructure initiative. To support this initiative, the country defined three guiding standards: “resilient”, “inclusive”, and “sustainable”. Indonesia – one of Japan’s key partner countries – endorsed the code of conduct for responsible lending, with other developing and emerging economies following suit. China had no grounds on which to reject the Japanese code. At the 2019 G20 Summit, the Japanese criteria for quality infrastructure were formally adopted.40

Later that same year, the United States established the Development Finance Corporation (DFC). As stated on its website, “DFC investments in infrastructure and critical minerals help address the multitrillion-dollar global gap for infrastructure financing, and counter China’s growing influence around the world.”41 By that point, the share of tied aid in Japan’s overall ODA had risen once again to 36 per cent. The DAC average stood at 22 per cent,42 while Germany reported 16 per cent.43

Where does Japan’s ODA go?

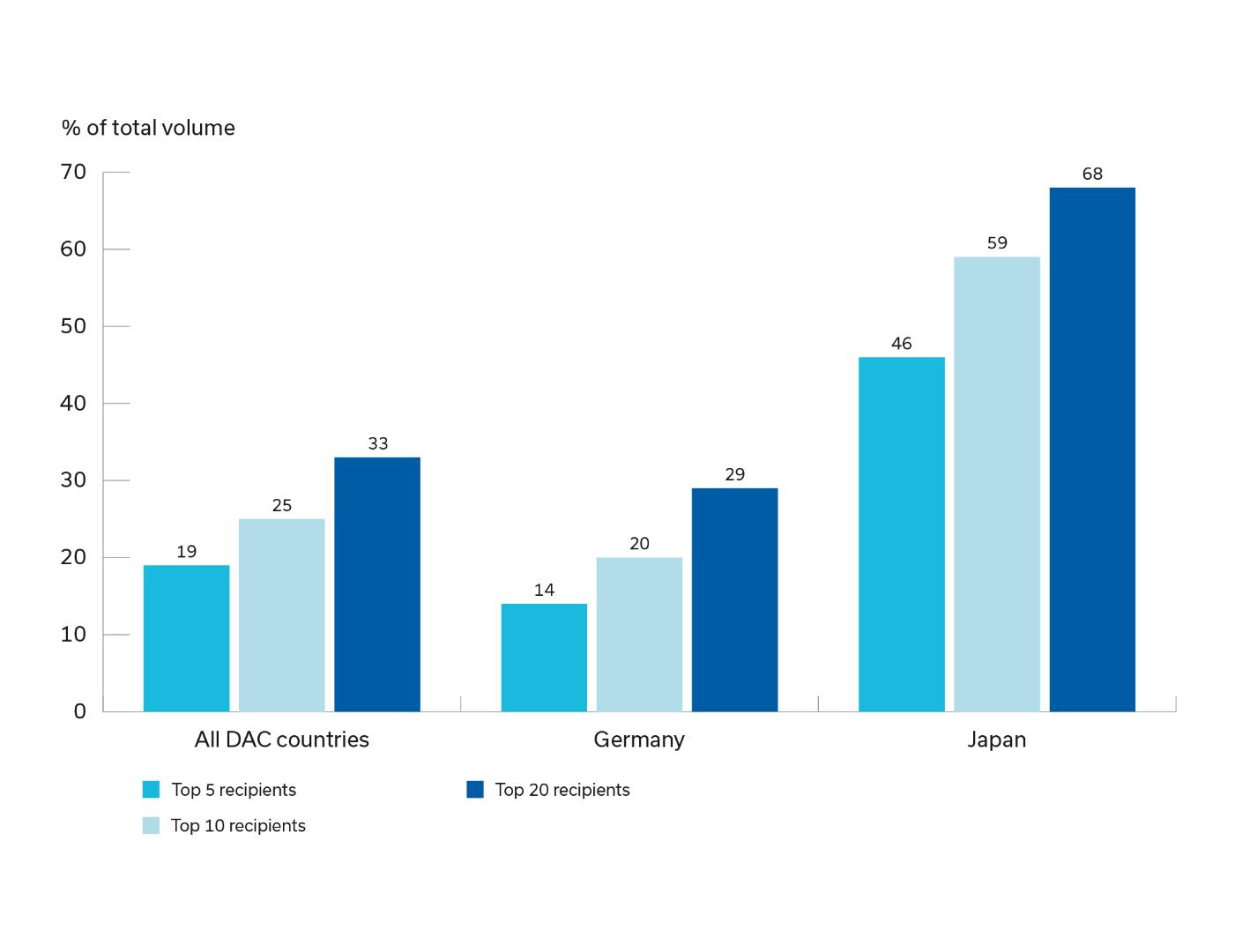

In 2023, Japan’s top ten recipient countries by financial volume (in decreasing order) were India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Iraq, Indonesia, Ukraine, Vietnam, Myanmar, Egypt, and Cambodia. These ten countries alone accounted for nearly 60 per cent of Japan’s total ODA (see figure 3). By comparison, Germany’s top 20 recipient countries together accounted for just 29 per cent of its ODA. Even against the DAC average, Japan showed a much higher degree of concentration in its development cooperation.

Fig. 3: Concentration of bilateral ODA on main recipients

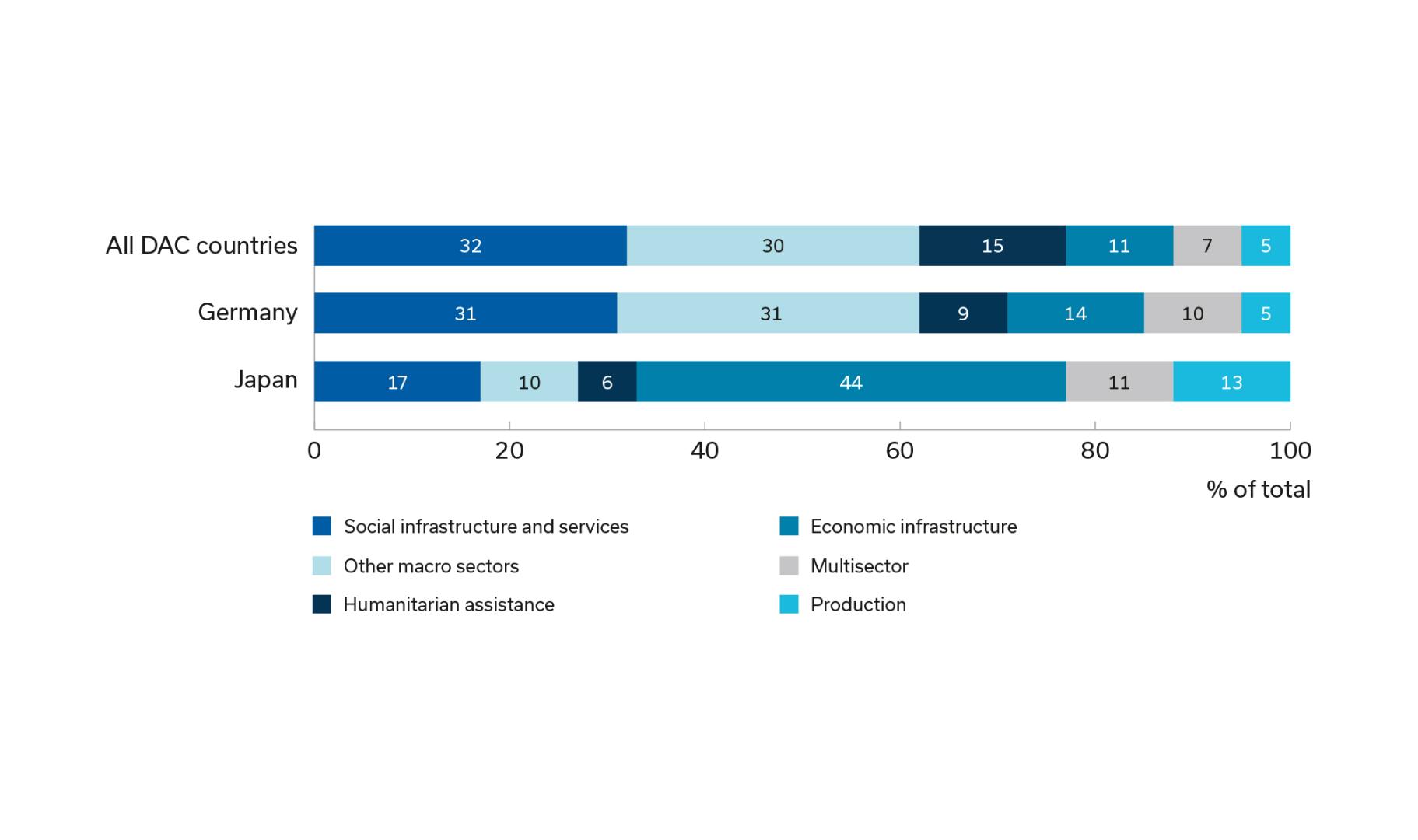

Another notable feature is the large share of Japan’s ODA that was allocated to economic infrastructure projects (see figure 4). This sector is far less prominent in the ODA profiles of Germany and the DAC average. Japan also placed greater emphasis on the productive sector, which accounted for around 13 per cent of its bilateral ODA – a higher proportion than in Germany or among DAC countries overall.

Fig. 4: Bilateral ODA by sector

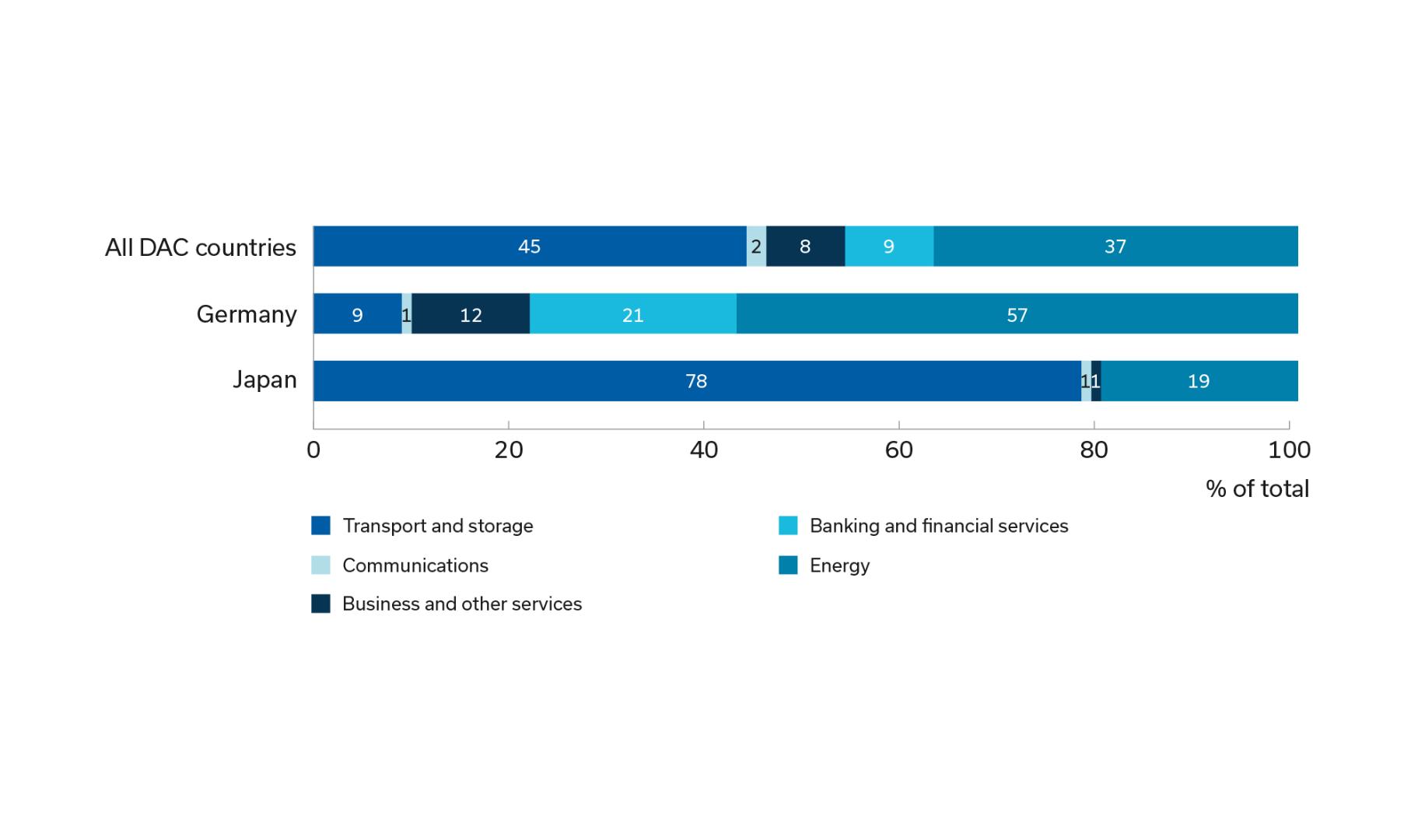

While Germany devoted by far the largest share of its ODA in this category to energy projects, Japan prioritized “transport and storage”, which accounted for nearly 80 per cent of its spending in this sector in 2023 (see figure 5). By contrast, Germany allocated just nine per cent to this area, which was well below the DAC average.

With its continued use of tied aid, its strong focus on a few key emerging economies, its emphasis on economic infrastructure, and its growing coordination with the private sector, Japan’s bilateral ODA is well positioned to continue leveraging the traditional trinity of aid, trade, and investment for its own benefit. However, that alone is not enough.

Fig. 5: ODA by type of economic infrastructure

Development and the shifting geopolitical landscape

The challenge lies in the fact that “the division of roles between the public and private sectors in development cooperation is changing”.44 Private Japanese companies now invest significantly more in developing countries than does the government. Between 2021 and 2022, Japan’s net ODA rose from 15.7 billion to 16.7 billion US dollars. At the same time, private financial flows surged from 21.5 billion to 37.4 billion US dollars.45

In relation to China and India, Japan’s development cooperation and foreign economic policy in recent years have evolved in parallel with changing geopolitical demands. Japan stopped providing yen loans to China in 2007. Since then, India has become by far the most important recipient of Japanese ODA. While Japanese FDI in China fell by nearly 32 per cent between 2022 and 2023, reaching 3.8 billion US dollars, investment in India rose by 23 per cent, reaching around five billion US dollars.46

While Japan’s ODA and the geostrategic priorities of its government played a role in the shift in Japanese investment towards India, these items were ultimately of secondary importance to the investors themselves. What mattered most were India’s stable growth potential, market size, and wage levels as well as the skills of its workforce.47

In order to ensure that commercial enterprises – including increasingly powerful institutional investors, pension funds, asset managers, and insurance companies – not only take on a key role in development cooperation amid stiff competition with China, but also align their investment decisions with geopolitical priorities as well as with profit expectations, the Japanese government has significantly expanded its policy toolbox. Japan’s National Security Strategy – adopted at the end of 2022 – thus mandates that ODA be “strategically deployed” by the government, guided by the vision of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).48 In areas in which such strategic engagement cannot be covered – or legally funded – through ODA, a new instrument was introduced in 2023: Official Security Assistance (OSA). This tool also aligns with Japan’s arms export and technology transfer rules and is coordinated closely between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Security Secretariat,49 and the Ministry of Defence under the broader National Security Strategy. Like ODA, OSA is primarily aimed at developing countries. Its objective is to support “cooperation for the benefit of the armed forces and related organizations of recipient countries where the improvement of security capacities is considered important in terms of creating a desirable security environment for [the] country”.50 In this respect, development cooperation is also part of Japan’s security policy. Indeed, Tokyo views such cooperation as “one of the most important tools of [Japan’s] diplomacy”.51

The close interlinking of security, development, and economic interests is an approach that could also offer valuable insights for German and European development policy. As Japan’s experience shows, emergency aid for the poorest of the poor on the one hand and investment in transport infrastructure on the other hand need not be mutually exclusive. Twenty-five years ago, during a famine in Sudan, Rania Dagash-Kamara – now the Deputy Executive Director of the World Food Programme – was asked what was needed most urgently. Her answer: “I have food rotting two states away and a famine this side – roads will fix this.”52

Even then, public finance expert Andrew H. Chen argued that the successful funding of major infrastructure projects “should be guided by the capital markets’ invisible hand”. He believed: “The fundamental challenge of infrastructure financing, then, is how to match the massive demand for capital investments in the world with a supply of capital from millions of private investors through project securities available on a global scale.”53 At the 2024 G7 Summit, Larry Fink – co-founder, chairman, and CEO of the world’s largest asset management firm, BlackRock – echoed this view: “The IMF and the World Bank were created 80 years ago when banks, not markets, financed most things. Today, the financial world is flipped. The capital markets are the biggest source of private-sector financing, and unlocking that money requires a different approach than the bank balance sheet model.”54

In Japan, such trends are closely monitored and actively debated in both the political and the business domain. Perhaps this is one of the key lessons Germany and Europe could learn from Japan’s approach to development cooperation: namely a heightened sensitivity to emerging dynamics and a willingness to engage openly with both relevant developments and influencing factors.

– translated from German –

Paul Linnarz is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Japan Programme and of its Regional Programme Economic Governance in Asia, based in Tokyo.

- Donor Tracker, Japan marks 70 years of ODA, Donor Tracker Website, published 14 June 2024, https://ogy.de/hzhg, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- Shuhei Nishitateno, “The Return to Overseas Visits by Political Leaders: Evidence from Japanese yen loan procurement auctions”, in The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) Discussion Paper Series, vol. 24-E-057 (2024), https://ogy.de/8fsx, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 1. ↩︎

- Shuhei Nishitateno, “Does Official Development Assistance Benefit the Donor Economy? New evidence from Japanese overseas infrastructure projects”, in RIETI Discussion Paper Series, vol. 23-E-029 (2023), https://ogy.de/fl58, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 1. ↩︎

- Saori Ono and Takashi Sekiyama, “Re-Examining the Effects of Official Development Assistance on Foreign Direct Investment Applying the VAR Model”, in Economies, vol. 10, no. 10, published 23 September 2022, https://ogy.de/4dqq, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 15. ↩︎

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA), Development Cooperation Charter. Japan’s Contributions to the Sustainable Development of a Free and Open World, MOFA Website, published 9 June 2023, https://ogy.de/vj0u, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 3. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 5. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 13. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 4. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 6. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 18. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 13. ↩︎

- Jin Sato, “Yōsei-Shugi: The Mystery of the Japanese Request-Based Aid”, in Jin Sato and Soyeun Kim (eds.), The Semantics of Development in Asia – Exploring ‘Untranslatable’ Ideas Through Japan (The University of Tokyo Studies on Asia: 2024), pp. 113–128, https://ogy.de/bmcj, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 114. ↩︎

- Nancy M. Birdsall et al., The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), published 1993, https://ogy.de/s939, accessed 21 July 2025, p. 1. ↩︎

- Ashoka Mody and Michael Walton, Building on East Asia’s Infrastructure Foundations, in IMF Finance & Development, vol. 35, no. 2, published 1 January 1998,https://ogy.de/62bw, accessed 21 July 2025. ↩︎

- MOFA, Japan’s International Cooperation: Japan’s Official Development Assistance White Paper 2014, MOFA Website, published 22 December 2015, https://ogy.de/5jtu, accessed 21 July 2025, p. 3. ↩︎

- Hirohisa Kohama, “Japan’s Development Cooperation and Economic Development in East Asia”, in Takatoshi Ito and Anne O. Krueger (eds.), Growth Theories in Light of the East Asian Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 201–226, https://ogy.de/fj7w, accessed 21 July 2025, here pp. 217 f. ↩︎

- MOFA 2015, n. 19. ↩︎

- Anthony Kiernan et al., DAC Working Party on Development Finance Statistics: Monitoring ODA grant equivalents, OECD, published 14 April 2025, https://ogy.de/1c2p, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- OECD, Official development assistance at a glance, OECD Website, published 27 July 2025, https://ogy.de/lrpf, accessed 21 August 2025. ↩︎

- For an explanation, cf. Deutscher Bundestag, Wissenschaftliche Dienste, Official Development Assistance (ODA). Definition, Entwicklung, Kritik, WD 2 – 3000 – 072/23, published 26 October 2023, https://ogy.de/hm43, accessed 25 June 2025. The grant equivalent reflects the cost to donor countries and their taxpayers of providing concessional loans. The more “generous” the loan conditions, the higher the grant equivalent. ↩︎

- OECD, Development Cooperation Profiles. Japan, OECD Website, published 17 June 2024, https://ogy.de/j44l, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- MOFA 2023, n. 5, p. 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 4. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 12. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 15. ↩︎

- Anna Nishino, Japan to bring companies into planning development aid projects, Nikkei Asia, published 16 December 2023, https://ogy.de/j9rq, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), 5th Japan-Arab Economic Forum, published 2024, https://ogy.de/nmuc, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), JETRO, JICA, UNDP, and UNIDO team up to boost innovation and investment in Africa, press release, JETRO Website, published 28 August 2022, https://ogy.de/ig9u, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- Republic of Ghana, Ministry of Finance, “We will Protect and Sustain Economic gains to Attract more Investment and Support for our Mutual Benefit” – Hon Stephen Amoah Assures JICA and JETRO Leadership, Republic of Ghana, Ministry of Finance Website, published 28 Aug 2024, https://ogy.de/rofk, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- Anthony Kiernan et al. 2025, n. 22. ↩︎

- Takagi, Shinji, “From Recipient to Donor: Japan’s Official Aid Flows, 1945 to 1990 and beyond”, in Essays in International Finance, no. 196 (New Jersey: Princeton University, 1995), https://ogy.de/zin8, accessed 21 July 2025, p. 26. ↩︎

- OECD, Peer Review. Japan. Development Assistance Committee, OECD Website, published 2004, https://ogy.de/p1u9, accessed 21 July 2025, p. 35. ↩︎

- OECD, Japan. Development Assistance Committee (DAC). Peer Review, OECD Website, published 2010, p. 48, https://ogy.de/4fpo, accessed 21 July 2025. ↩︎

- Shiga, Hiroaki, “Yen Loans: Between Norms and Heterodoxy”, in Jin Sato and Soyeun Kim (eds.) 2024, n. 16, pp. 195–208, here pp. 202 f. ↩︎

- MOFA, G20 Osaka Leaders’ Declaration, MOFA Website, published 2019, https://ogy.de/m656, accessed 21 July 2025. ↩︎

- America’s Development Finance Institution (DFC), Infrastructure and Critical Minerals, DFC Website, https://ogy.de/8o0q, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, Japan. Development partner monitoring profile, Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation Website, published 2022, https://ogy.de/p5g1, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- UNDP and Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation, Germany. Development partner monitoring profile, Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation Website, published 2022, https://ogy.de/iylc, accessed 25 June 2025. ↩︎

- MOFA 2023, n. 5, p. 20. ↩︎

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Japan, Statistical Handbook of Japan 2024, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Japan Website, published 2024,https://ogy.de/b0jp, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 120. ↩︎

- JETRO, JETRO Global Trade and Investment Report 2024, JETRO Website, published July 2024, https://ogy.de/uo4e, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 22. ↩︎

- Saori Ono and Takashi Sekiyama, “The impact of official development assistance on foreign direct investment: the case of Japanese firms in India”, in Frontiers in Political Science, vol. 6 (2024), https://ogy.de/tweo, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 5. ↩︎

- MOFA, National Security Strategy of Japan, MOFA Website, published 16 December 2022, https://ogy.de/xtcg, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 17. ↩︎

- Comparable with the US National Security Council. ↩︎

- MOFA, Implementation Guidelines for Japan’s Official Security Assistance, published 5 April 2023, https://ogy.de/h66o, accessed 25 June 2025, p. 1. ↩︎

- MOFA 2023, n. 5, p. 4. ↩︎

- Adarsh Kumar, Making Development Finance Work Smarter in a Shifting Climate and Political Landscape, Harvard Center for International Development Website, published 17 June 2025, https://ogy.de/z6s1, accessed 21 July 2025. ↩︎

- Andrew H. Chen, Rethinking Infrastructure Project Finance, Southern Methodist University Website, published 17 November 2004, https://ogy.de/3bix, accessed 21 July 2025, pp. 14 f. ↩︎

- Larry Fink, My Speech at the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment in Italy, LinkedIn, published 13 June 2024, https://ogy.de/bv5y, accessed 21 July 2025. ↩︎