Issue: 2/2025

- Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government has negotiated the transfer of the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean – which have thus far been under British administration – to Mauritius. The agreement highlights the ongoing tension between colonial reckoning and restitution on the one hand and national (security) interests on the other hand.

- At no point did the UK government consider relinquishing the military base on the archipelago, which it runs jointly with the US; the newly negotiated treaty grants the UK an initial 99-year lease, with the option of a further 40-year extension to be activated by mutual agreement of the parties.

- Public debate continues in the UK over the Empire’s failings and achievements. Labour and the Conservatives are united in rejecting reparations, but the Conservatives have criticised what they see as a growing “culture of self-doubt” and are keen to uphold a positive national self-image in this debate.

- Brexit was accompanied by the promise of greater freedom in foreign policy and by the hope that economic losses from leaving the EU could be offset by reinvigorating ties with the Commonwealth – a hope that has gone largely unfulfilled.

The renewed public attention on the Chagos Islands has revived the broader national debate on decolonisation, which is reflected not only in party-political discourse, but also in public opinion, where questions of guilt and responsibility are becoming increasingly divisive. Reckoning with the British Empire remains central to the construction of national identity and is a key factor influencing how the UK views the world.

Ultimately, Britain’s imperial past also casts light on some of the deeper causes of Brexit. With its “Global Britain” strategy, the UK sought to decouple from the EU and to reforge its historical ties with the Commonwealth both economically and politically. But how successful has this approach been in practice? The attempt to offset economic losses through stronger links with former colonies has proved more complex than anticipated. Indeed, British foreign policy now finds itself caught between the legacy of empire and the challenge of global repositioning.

Between Justice and Security: The Chagos Islands

When Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced in October 2024 that the UK would be transferring sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, he was not expecting a heated security policy debate over the potential costs and consequences. Labour’s goal had been to finalise the process – initiated in 2019 by Boris Johnson – of returning what had been described as “Britain’s last African colony”, and to do so before Donald Trump returned to the White House.

Whereas previous Conservative governments had repeatedly postponed a decision, Labour viewed itself as being forced to act after several legal opinions had indicated that Mauritius would likely win a case before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Such a defeat would have meant losing the entire archipelago – and with it, also significant strategic assets. The Starmer government sought to pre-empt such a worst-case scenario from the perspective of its own national security interests and opted for a proactive approach by attempting to reach a negotiated agreement with Mauritius. In addition to strategic considerations, the handover also presented Prime Minister Starmer with an opportunity to demonstrate the UK’s commitment to international law and the nation’s global obligations.

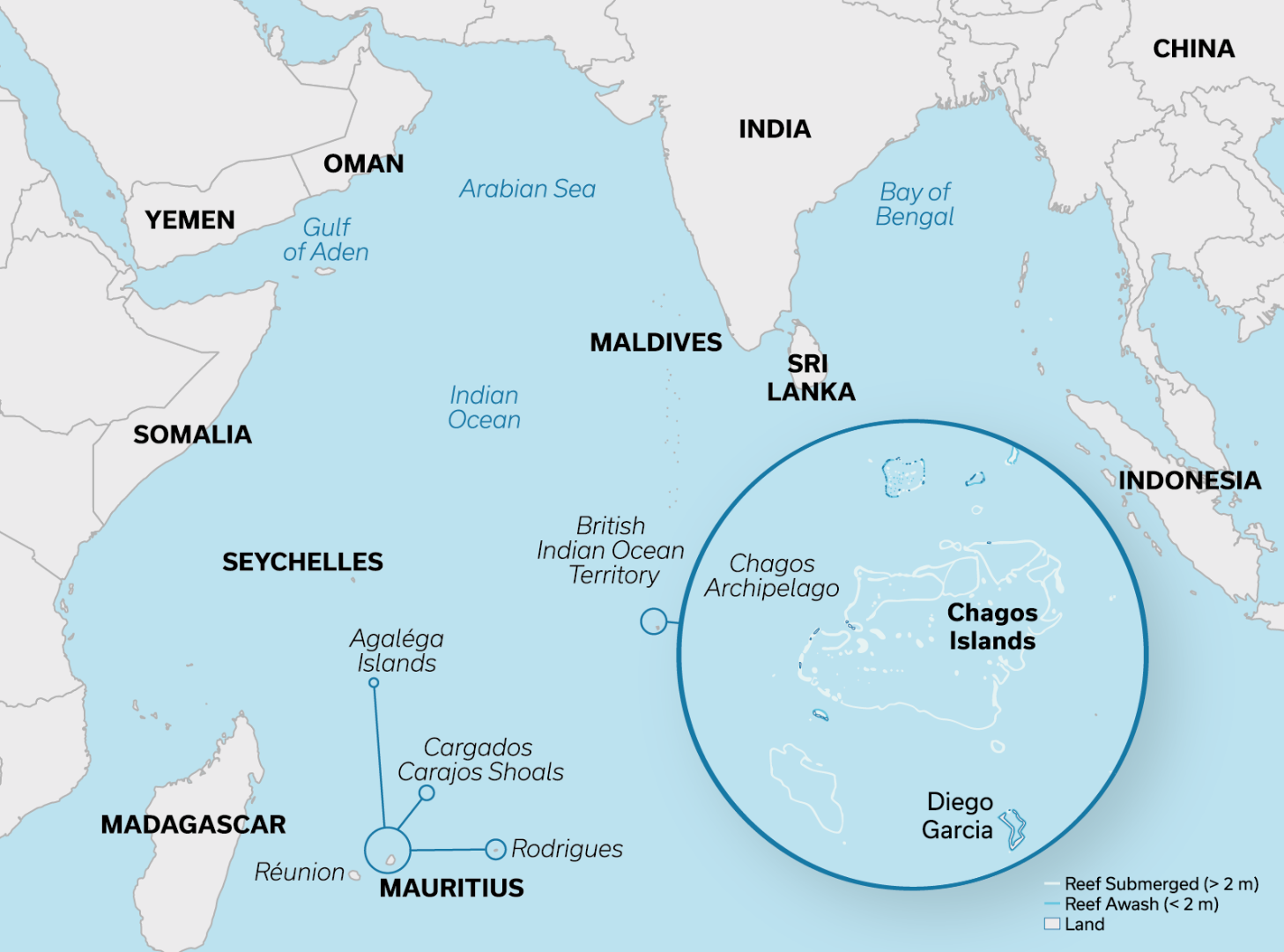

The historical claim of Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago remains contested, thereby making the rectification of “historical injustices” more complicated than it might initially appear. The link between the two territories stems mainly from their shared colonial administration – first under French, then under British rule. In 1965, the administration of the Chagos Islands was separated from Mauritius and was placed under direct British control as the British Indian Ocean Territory. The UK had made this step a precondition for granting independence to Mauritius. In the late 1960s, between 1,500 and 2,000 Chagossians were forcibly removed to make way for a US military base on the main island of Diego Garcia. Aside from this military base, the islands are now uninhabited.

Diego Garcia hosts one of the most important US military installations in the Indian Ocean – a key hub for air operations, maritime surveillance and logistical support for missions in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa. The CIA has also used the site for covert operations, as confirmed by Lawrence Wilkerson, former Chief of Staff to US Secretary of State Colin Powell. Most recently, strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen were coordinated from the base. In light of China’s growing regional presence, the base is widely viewed as a crucial outpost for projecting US power in the region.

Both the separation of the islands and the displacement of the local population had already been deemed a violation of international law in a non-binding advisory opinion issued by the ICJ in 2019. Endorsed by an overwhelming majority of the UN General Assembly, the opinion called on the United Kingdom to return the islands to Mauritius “as soon as possible”. For the new British Prime Minister, this was reason enough – five years later – to pursue a negotiated agreement with Mauritius. An initial deal had already been reached by October 2024, just a few months after Starmer had taken office. Due to changes in government in both Mauritius and the United States, however, the agreement had to be renegotiated and revised.

Fig. 1: Location of the Islands of the Chagos Archipelago and of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean

The breakthrough finally came during Keir Starmer’s visit to Washington in April 2025 after US President Donald Trump had agreed to the deal. Having described the UK’s planned handover just weeks earlier as a betrayal, Trump now accepted the originally proposed 99-year lease, not least because an optional 40-year extension was negotiated, to be activated by mutual agreement of the parties. A key figure in securing this outcome with the White House was Jonathan Powell, the UK’s National Security Adviser. It was largely thanks to him that the US side was persuaded to view an agreement with Mauritius as the most effective way to pre-empt any future legal challenges to the use of the base.

The agreement brought months of uncertainty to an end, though criticism continues in both the UK and the US. In particular, Republican lawmakers in Washington and Conservative figures in the UK have expressed concern about financial burdens and potential security risks, particularly given the close ties between Mauritius and China. One of the most vocal critics on the US side is Senator John Kennedy, who has repeatedly stressed that despite billions in US investment and formal agreements, the strategic use of the military base is by no means guaranteed. Mauritius, he warned, could exploit the situation to pressure Washington with excessive lease demands while Beijing continues to expand its influence in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Meanwhile, the opposition Conservative Party accused the Starmer government of allowing excessive legal caution to distract from the UK’s national security interests and to jeopardise its strategic advantages.

The criticism thus extends far beyond party-political or domestic issues and primarily highlights the security policy implications of the agreement. The Chagos question concerns not only American and British interests, but also those of NATO allies, who share a common interest in maintaining Western influence in this strategically important region. Destabilising the security architecture in the Indian Ocean could have lasting consequences for global defence strategies. In this context, the Chagos case is more than a question of decolonisation.

The agreement – as well as the debate surrounding it – highlights both how slow and how difficult the process of coming to terms with Britain’s colonial past remains and how complex the notion of “reparation” can be. However, the agreement also highlights the UK’s geopolitical priorities: Given the potential impact on both its partnership with Washington and its own national security, a full loss of the territory and the military base was never an option for London. Consequently, from the very beginning, the government ruled out any return of the islands that would have bypassed US consent. The UK’s handling of the Chagos agreement suggests a country navigating a delicate balancing act between historical accountability and national security interests.

Britain’s Colonial Debate: Between Guilt and Pride

Britain’s colonial past remains a recurring topic in public discourse. A major turning point came during the COVID-19 lockdown, when the Black Lives Matter movement spread from the US to the UK. Nationwide protests against racism and colonialism prompted a reckoning with Britain’s imperial history. One defining moment was the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston – a slave trader long honoured as a philanthropist – by demonstrators in Bristol in June 2020. Universities and cultural institutions across the country expressed solidarity and began re-examining their own colonial legacies. Demands for critical engagement with Britain’s imperial past gained momentum, including calls for education reform, the removal of monuments and discussions on reparations. A symbolic occasion came with King Charles III’s visit to Kenya in October 2023, during which he expressed “deepest regret” for the “abhorrent and unjustifiable” violence committed during British colonial rule – though he stopped short of a formal apology. Human rights organisations criticised this reluctance and called for an unreserved apology. The UK government continues to reject both formal apologies and financial reparations, however, instead showing a willingness to consider indirect forms of redress, such as debt relief and development cooperation.

While the form of compensation remains contested, the terms of debate have also shifted. The conversation is no longer shaped only by traditionally anti-colonial voices: Increasingly often, conservative actors are now promoting a more affirmative national narrative that emphasises the “achievements” of the British Empire.

The prominent argument is that it was the British Empire – through its naval power – that abolished the transatlantic slave trade, and this well before the US Civil War. Groups such as History Reclaimed aim to “challenge distortions of history and bring context, explanation and balance to a debate in which dogma often overrides analysis, and condemnation trumps understanding”. One of the group’s leading figures, Nigel Biggar, argues in his 2023 book “Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning” that a more differentiated approach is required and that the Empire should not be viewed exclusively in negative terms. He contends that British colonialism not only ended practices such as slavery, widow-burning and human sacrifice, but that it also left lasting legacies – such as the rule of law, effective governance and education systems – that still benefit former colonies. Biggar was appointed a life peer at the instigation of Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch in January 2025 and now sits in the House of Lords.

Biggar’s work bolsters Badenoch’s campaign to restore confidence in Western civilisation. The Conservative Party sees itself as defending a positive national self-image in the colonial debate. Its members argue that despite the nation’s imperial past, Britain has reason to be proud. Badenoch in particular often cites a study suggesting that nearly half of young Britons view their country as racist – a finding that she uses to criticise what she views as divisive and one-sided narratives that foster a culture of self-doubt. For today’s Conservative leadership, calls for reparations reflect a never-ending narrative of guilt that is driven primarily by the political Left. Britain’s prosperity and progress, the Tories argue, stem not just from colonialism, but from a diverse and capable society. Former Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick went even further, suggesting that former colonies should show greater gratitude for the democratic institutions inherited from the Empire. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party leader has linked the emergence of authoritarian regimes in some African states to a rejection of British values.

A closer look at the British Empire reveals why debates over its colonial legacy remain so complex, deeply divisive and firmly embedded in public discourse. Over centuries, imperial dominance not only shaped the global geopolitical order, but also forged a distinct British self-image – one that often carried more weight than a European sense of belonging. The Empire granted Britain major economic advantages, control over global trade routes and worldwide influence. This dominance fed into a romanticised view of colonialism that still resonates in parts of society. Undoubtedly, the colonial nature of the Empire contributed to industrialisation, technological leadership and the development of a global social and political perspective. However, this nature was also underpinned by racist hierarchies, systematic exploitation and a deeply entrenched sense of superiority. A more measured view reveals that the impact of colonialism varied considerably from region to region. Settler colonies such as Australia and New Zealand experienced comparatively successful development, while countries with large Indigenous populations often suffered severe long-term political and economic burdens.

The darker sides of the Empire are beyond dispute, which is why the UK is under growing pressure to respond to demands for reparations. At the 2024 Commonwealth Summit in Samoa, member states called for a meaningful, truthful and respectful dialogue on the issue of reparations – especially in relation to the transatlantic slave trade. The UK did indeed play a major role in this trade and did not begin to actively combat it until the passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. For both Labour and the Conservatives, however, financial compensation has never seriously been on the table. There is cross-party agreement in Britain that this particular can of worms should remain closed. Prime Minister Keir Starmer has likewise repeatedly reaffirmed this position, even while expressing a general openness to dialogue on addressing Britain’s colonial past. This openness not only serves to support his agenda of colonial reckoning, but also reflects the fact that a significant part of the UK’s post-Brexit economic strategy depends on trade and relationships with Commonwealth countries.

Brexit, the Commonwealth and Global Britain

A longstanding belief in Britain’s global significance continues to shape the country’s foreign policy outlook. One of the clearest examples of this is Brexit itself – arguably the most far-reaching political decision in recent UK history. For many of its supporters, leaving the European Union was closely tied to the restoration of national sovereignty, which in particular involved regaining control over trade policy and the ability to strike independent agreements around the world. Britain aimed to become “global” again, and “Global Britain” became the official foreign policy strategy under the Conservative government. In this way, London sought to redefine its influence within a changing international order. Even before the 2016 Brexit referendum, certain narratives and slogans shaped the debate: taking back control, shifting decision-making power from Brussels to London, the notion that Commonwealth trade could offset the effects of Brexit and the hope of reviving historical global ties.

It is therefore unsurprising that after leaving the EU, the UK placed particular emphasis on the Commonwealth and its 56 member states, many of them former colonies. The aim was to revive old trade routes, to reassert regional influence and to make economic use of historical relationships, particularly in Africa. Countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya and Ghana were identified as strategic partners in promoting economic development, security and stability across the continent.

However, the strategy of using Brexit to revitalise historical Commonwealth ties and to generate new economic opportunities under the banner of Global Britain has proved only partially effective. While the Commonwealth may appear to offer London privileged access through its geopolitical network, the reality is far more complex. Former colonies have long been asserting their economic and political independence, increasingly seeking new partnerships and pursuing their own interests. In this context, historical power structures are losing relevance, and Britain is being forced to position itself as an equal partner.

The ambition to redirect the UK’s external trade flows and global influence via the Commonwealth has not materialised as hoped, as is clearly reflected in the numbers. While post-Brexit trade with the EU has seen only a minor decline, trade with the Commonwealth has stagnated despite Britain’s regained autonomy in global trade. In 2023, only about 10 per cent of UK exports went to Commonwealth countries – barely more than before Brexit. The Commonwealth accounts for around 13 per cent of global GDP, while the EU’s 27 member states generate roughly 14.7 per cent. Even so, trade with the EU remains the cornerstone of Britain’s international commerce.

British development policy also reveals tensions between rhetoric and reality. On the one hand, London repeatedly emphasises its intention to deepen cooperation with countries in the “Global South” – not least to defuse calls for reparations. On the other hand, however, the government’s announcement of cuts in development aid sends a contradictory message and seriously undermines the credibility of its partnership ambitions. Aid now accounts for only 0.5 per cent of gross national income and is set to fall even further. Prime Minister Starmer has even proposed reducing this figure to 0.3 per cent in order to increase defence spending. Since 2019, UK Official Development Assistance to Commonwealth countries has already fallen by 70 per cent – from 1.88 billion to just 570 million pounds in 2023.

How strong the UK’s future relationships with its former colonies will be ultimately depends on two factors: the level of investment in these relationships, and the alignment of interests, as illustrated by the contrasting examples of Singapore and India. In the case of Singapore, Britain has achieved some success. The 2021 free trade agreement and the 2022 Digital Economy Agreement build on mutual strengths in the services sector. As early as in 2020, bilateral trade exceeded 22 billion US dollars, thereby providing a solid foundation for further growth. India, by contrast, has proved a more difficult partner. Although Prime Minister Johnson agreed on an ambitious 2030 Roadmap with India in May 2021 that would cover cooperation on trade, climate, health and defence, progress has remained limited. Negotiations on a free trade agreement were suspended at times, and it was not until May 2025 that the UK and India concluded a comprehensive deal after years of wrangling.

Brexit and the Global Britain strategy are both expressions of a broader search for a foreign policy identity. Ultimately, neither have delivered on the ambitious goals they set. Brexit embodied a hope shaped by historical and national identity, yet it failed because this hope no longer aligned with the realities of Britain’s global influence. It has since become clear that Global Britain faces significant real-world challenges. The hoped-for revitalisation of the Commonwealth as an economic and political bloc has thus far only materialised in limited ways. Many member states are not economically reliant on Britain and increasingly assert their own priorities, thereby diminishing the significance of historical connections. In addition, more and more Commonwealth countries now expect the UK to engage credibly with its colonial legacy as a prerequisite for deepening ties.

Outlook

Britain’s imperial past remains a defining element of national identity, yet this past is becoming increasingly at odds with the political and economic realities of the 21st century. Coming to terms with colonial history continues to pose an unresolved challenge for both domestic and foreign policy. The debate will remain part of public discourse – at times more prominent, at others more subdued, and shaped by shifting perspectives ranging from critical engagement with colonial wrongdoing to the nostalgic idealisation of the Empire. It is precisely this ambivalence that shapes Britain’s national self-image today. The United Kingdom now faces the task of developing a balanced identity – both at home and in its foreign policy – that acknowledges its colonial legacy while also meeting contemporary ethical standards.

The country’s future role in global affairs will largely depend on how credibly it can move beyond outdated imperial thinking while simultaneously harnessing the potential of the Commonwealth to serve its own strategic interests. Only under these conditions will the UK be able to secure a lasting and relevant role on a multipolar world stage – a role that genuinely reflects the country’s ambitions as a global power.

Since the government’s revised Integrated Review of 2023 – which may be seen as a realignment of Britain’s global role – new geopolitical realities have begun to influence strategic thinking. The new Labour government has pursued a noticeably more pragmatic course. Rather than positioning itself as a global power in the imperial tradition, Britain has placed greater emphasis on international partnerships in an effort to redefine its role in a multipolar world. The focus is now on cooperation – particularly within both NATO and the G7 as well as with the EU. In hindsight, Global Britain appears less a realistic foreign policy strategy than a post-Brexit identity project – a narrative that has ultimately failed to withstand geopolitical realities. The current government is now attempting to combine its outreach to the Trump administration with an equally ambitious policy towards the EU. Looking back, Brexit may ultimately prove to have been an opportunity for the UK to re-emerge from years of global retreat – and to define a new and meaningful role for itself between both sides of the Atlantic.

– translated from German –

Dr Canan Atilgan is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s UK and Ireland Office, based in London.

Lukas Wick is Research Associate at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s UK and Ireland Office.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.